Israel’s response to the threats facing cultural heritage

22 February 2019

By Dr Eitan Klein and Ilan Hadad, Antiquities Theft Prevention Unit, Israel Antiquities AuthorityThe State of Israel has a rich history, with more than 30,000 known antiquity sites across the country. Most of these sites are out in the open, unguarded, and easily reached by the public. Neighbouring countries, such as Jordan, Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Iraq and Turkey, are in the same situation, but, contrary to Israel, they do not permit any trade in antiquities.

In Israel, this trade is regulated by the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) and the country counts more than 40 antiquity dealers, most of whom are located in Jerusalem and the surrounding area. They must operate in accordance with the Israeli Antiquities Law, enacted in 1978, which stipulates that every antiquity that has been excavated or found in Israel after 1978 is state property. The Law also stipulates that excavations of archaeological sites are allowed only for scientific research and require excavation licences.

Illegal trade

Given this background, the question which naturally arises is: where do the antiquities in the dealers’ shops come from? They may, of course, have been obtained from private collectors or date back to pre-1978, but unfortunately this is not always the case, as some objects are acquired illegally. Sites are being looted on a mass scale all over the State of Israel, especially in the Judean Hills and the surrounding area of Jerusalem. This illicit trade is carried out by organized gangs of professional thieves who systematically dig up antiquity sites, break into burial caves, and completely destroy ancient structures.

In the Judean hills alone, 6,200 burial caves have been broken into, and Biblical Tels (mounds formed over a period of several millennia that contain evidence of multiple layers of settlements, representing various civilizations) have been dug up in the search for graves. Underground cave complexes linked to the Great Revolt (66-73 CE) and the Bar Kokhba Revolt (132-136 CE) against the Romans have been systematically plundered in an attempt to find valuable coins from those periods.

As a result, entire pages of history have been wiped out by the robbers’ spades and excavators. Antiquity sites destroyed by robbers afford no possibility for archaeological research since the original order of chronological levels supplying evidence of thousands of years of habitation has been destroyed. Often what is most important for archaeologists and other scholars is studying objects in context: how they relate to each other; and how they relate to where they have been found. Once coins, pottery and glass objects, for example, are removed from their context, a lot of knowledge is nearly impossible to put back into place, and it is almost impossible to study the material culture of the site.

Supply in illegally excavated items also comes from abroad. As Israel is the only country in the Middle East with a legal antiquities market, there are many attempts to smuggle looted artefacts into the country. Before the requirement for an import permit came into force in 2012, these objects were entering the country without having to be declared, and subsequently being sold to antiquity dealers. Although the latter are obliged to keep an inventory of their stocks, some launder illicit items by registering them in their inventories in place of unreported sold items. This fraudulent behaviour enables illicitly acquired antiquities to be “legally” sold on the open market in accordance with Israeli law.

Enhancing protection

The efforts of the Antiquities Theft Prevention Unit (ATPU) of the IAA to overcome this phenomenon consist of several activities that include:

- regular monitoring of archaeological sites by ATPU inspectors, in order to catch looters in the field and ensure that they are effectively prosecuted and punished;

- the Unit’s experts making use of covert methods and informants to feed the intelligence system and back up enforcement operations;

- monitoring and inspecting the antiquities market and dealers’ inventories;

- monitoring the Internet and online market platforms as well as social media for information on trade and the illegal trade in antiquities;

- cataloguing and digitizing private archaeological collections;

- undertaking surveys of and excavations at looted sites;

- cooperating with other national governmental services such as Customs, Border Control, the Police, the Army, the Tax Authority and the Nature and Parks Authority;

- assisting the general public.

Moreover, the ATPU, together with the IAA’s Legal Department, has made great strides in having a number of legislative changes adopted that were instrumental in preventing cultural property crimes. Some of these changes included: (i) a prohibition on bringing antiquities into Israel from the territory of the Palestinian Authorities in 2002; (ii) tightening up legislation relating to antiquity collectors and private collections in 2009; (iii) a new order requiring an import permit for antiquities to prevent the entry of looted artefacts from foreign countries and criminal laundering activities in 2012; and (iv) tougher regulation requiring computerized records and the photographing of all dealers’ inventories in 2015. Work is now underway on a new regulation that will include a licensing requirement for owning and using metal detectors.

International collaboration

The Israeli antiquities market is a major crossroad in the international trade in antiquities. As a result, Israel regularly shares information on items discovered and on other interesting cases with various international bodies, such as INTERPOL, the WCO, the International Institute for the Unification of Private Law (UNIDROIT), the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the International Council of Museums (ICOM), and law enforcement bodies around the world. It also conducts international investigations; a few cases illustrating this work are listed below:

Egyptian sarcophagus

During a visit to a dealer’s shop, the lid of an Egyptian sarcophagus was found; however, the dealer could not prove its provenance. Israel then contacted the Egyptian authorities through INTERPOL and the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs. As the item proved to be stolen, it was eventually returned to Egypt.

Iraqi items

Resolution 2199 of the United Nations Security Council states that all Member States are to take appropriate steps to prevent the trade in Iraqi and Syrian cultural property and other items of

archaeological, historical, cultural, rare scientific, and religious importance illegally removed from Iraq since 6 August 1990 and from Syria since 15 March 2011, including by prohibiting cross-border trade in such items, thereby allowing for their eventual safe return to the Iraqi and Syrian people. In Israel, during an enforcement operation, all Iraqi items on offer on the antiquities market were impounded while an investigation into their provenance was undertaken. Eventually, an Israeli Court ordered the confiscation of almost 200 ancient Iraqi items, and efforts are now underway to find an appropriate diplomatic path in order to return them to Iraq.

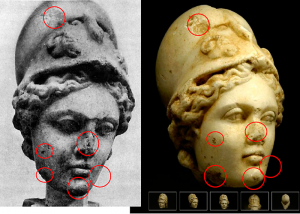

Minerva statue head

While attending a UNESCO conference, a representative of the Libyan government approached the Israeli delegation with a photo of a Roman marble statue head that was for sale on an Israeli antiquity dealer’s website. The representative also provided proof that the statue had been stolen from the Cyrene Museum in Libya. Back home, Israeli authorities initiated an operation against the dealer and succeeded in seizing the statue. Again, efforts are being expended to find the right diplomatic path to ensure the statue’s return to Libya.

Museum of the Bible

In 2016, a joint investigation into the activities of three Israeli antiquity dealers who had sold looted Iraqi artefacts to the Museum of the Bible in Washington D.C. was initiated in conjunction with an agent working for the Department of Homeland Security in the United States (US). This investigation led to the confiscation and retrieval of more than 5,000 Iraqi items. The museum was fined three million US dollars, and the Israel Tax Authority began investigating the three dealers on suspicion of tax evasion amounting to millions of US dollars.

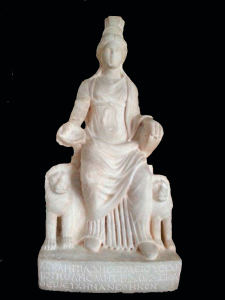

Cybele statue

A private collector in Israel wanted to sell a statue originating from Turkey in an auction house in America. When the collector applied for an export permit, Israel contacted INTERPOL to check that the item had not been stolen. As no answer was forthcoming after a long period of time, an export permit was eventually granted. Very soon after the item was exported from Israel, an answer was received from Turkey confirming that the item had been illegally acquired through looting. Israeli authorities immediately informed the US Department of Homeland Security, which seized the item on its arrival in the country.

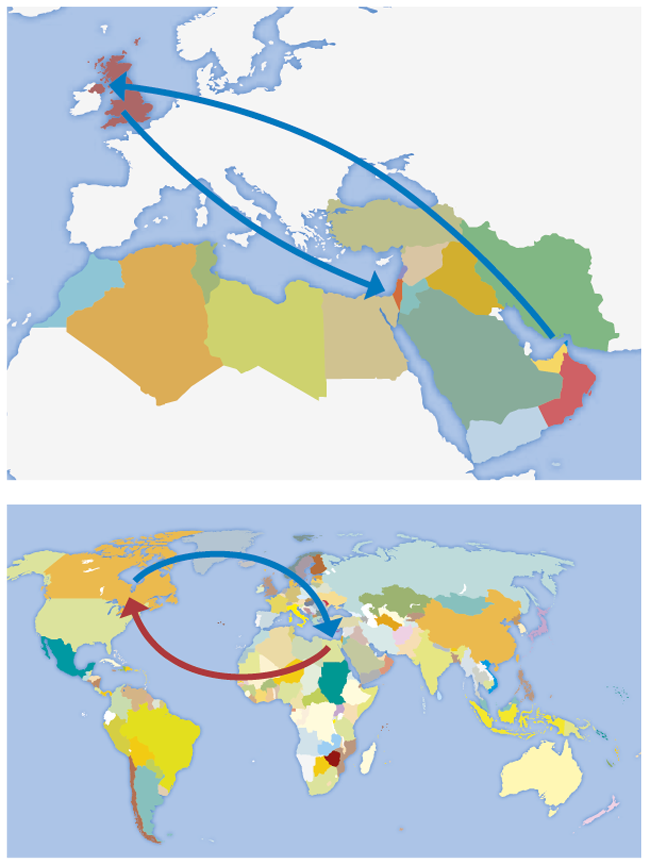

Illicit trafficking routes

Given Israel’s central role in the antiquities market, the ATPU has gathered information and intelligence on the routes used by smugglers of antiquities. Until 2012, looted items were smuggled from all around the Middle East to the free trade market in Dubai, from where they were shipped in transit to the United Kingdom and then on to Israel. Once in the country, the items were then laundered using licensed dealers’ inventories, and thereafter legally exported to destination countries in Europe and the US. However, everything changed in 2012 with the introduction of legislation requiring an import permit.

Also of note is the fact that a new illicit trade route for looted antiquities has recently been identified between Israel and other countries in the Middle East, and Canada. In Israel’s opinion, the law in Canada regarding the trade in antiquities is very loose, enabling international dealers to exploit the situation with the possible aim of also using this route to smuggle items onto the American market. These criminally-inspired actions have been brought to the attention of the Canadian authorities.

Another smuggling route, used mostly by Israeli dealers, is via border checkpoints between Israel and Jordan. Israelis and Palestinians, who work as drivers for foreign diplomats, take advantage of the diplomatic immunity afforded to their vehicles when crossing the border to smuggle hidden antiquities in these vehicles. Intelligence work and cooperation between the IAA and Israeli Customs play a key role in responding to this phenomenon.

Possible solutions

By acting on different fronts, the ATPU has managed, over the last few years, to lower the incidences of antiquities being looted and trafficked in and through Israel. But this harmful and devastating phenomenon is still occurring. Therefore, Israel strongly believes that it is the responsibility of the various bodies charged with controlling antiquities in each country to come together and, if necessary, amend Customs regulations pertaining to internationally traded antiquities or items of cultural heritage by requiring export permits for such goods in particular.

If each country required an importer to submit the export permit that was issued by the country where the item was purchased, items for which no provenance documentation is available would be more easily identified. Some dealers will, of course, falsify documents to hide the origin of antiquities, but close monitoring of market places and other activities described in this article would still be relevant to deal with such a phenomenon effectively, and an export permit would greatly help enforcement bodies in tackling any illicit trade.

In addition, the ATPU is of the firm belief that effective international cooperation between countries is also instrumental in combating the illicit trade in antiquities, as the examples provided in this article clearly demonstrate. Indeed, by working together, countries can more easily contain the threats facing cultural heritage, preventing not only the looting of such items, but also the lucrative trafficking in these objects.

More information

www.antiquities.org.il