No Entry: How CBP is fighting to keep African Swine Fever out of the United States

29 October 2024

By Marcy Mason, Writer, US Customs and Border ProtectionIn July 2021, while most of the world was focused on COVID-19, a dangerous foreign animal disease was discovered in the Western Hemisphere. African swine fever, a highly contagious and deadly viral disease that affects swine, was discovered in the Dominican Republic and then Haiti. But the disease, which was first documented in Kenya in 1909, was already on U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s radar. CBP’s agriculture specialists had been on high alert since 2018, when African swine fever was first detected in China, the No. 1 pork producing nation in the world, and then soon after emerged in neighboring Asian countries.

Although the disease is not a human health concern, the impacts are severe. African swine fever spreads quickly among domestic and wild swine herds, and it’s fatal. Currently there is no vaccine or cure. If the disease were discovered in the U.S., it would be an extremely dangerous threat to the country’s livestock and catastrophic for industry. “A single positive case of African swine fever in the U.S. would cease all exports immediately,” said John Sagle, acting executive director of CBP’s Agriculture Programs and Trade Liaison division. “We want to do everything we can to keep it out of the United States.”

According to the National Pork Producers Council, a trade association representing U.S. pork producers and other industry stakeholders, the pork industry supports more than 573,300 U.S. jobs and generates more than $62 billion of gross national product to the U.S. economy. In 2023, U.S. pork exports surpassed $8.2 billion in value and more than 6.8 billion pounds of pork were exported to other markets, making the U.S. one of the top two exporters of pork globally. “The industry exports somewhere between 25 and 30 percent of all product we produce,” said Dr. Liz Wagstrom, chief veterinarian for the National Pork Producers Council. “Shutting off exports would be devastating as far as creating a crash in the price of pork and an oversupply of pork in the United States.”

Moreover, the disease would be costly to eliminate. “If we contracted African swine fever and it became endemic in the U.S., it would take us over 10 years to eradicate the disease to the tune of about $80 billion and that’s just the swine industry,” said Dr. Jack Shere, the associate administrator of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal Plant Health Inspection Service and one of the world’s foremost experts in infectious veterinary diseases. “Economists can formulate it any way they want, but if we get it, it’s bad. It’s really bad. It’s going to cost the U.S. a lot.”

In July 2021, when African swine fever was reported in the Dominican Republic, CBP’s efforts to prevent the disease from entering the U.S. intensified. The close proximity to the U.S. added a new element of concern. “It’s the first time in 40 years that the virus has been in the Western Hemisphere,” said Shere. “It’s at our backdoor and even though we don’t import pork from these countries, it just brings it closer.”

The close proximity added more pathways of introduction. “We already had been dealing with the threat from other countries,” said Sagle. “Travelers and cargo had been the main potential sources of transporting the disease, but now our CBP agriculture specialists are also focused on smaller boats, vessels, and aircraft. All modes of entry into the United States for people and goods are a potential risk.”

Movement and spread of disease

The movement and spread of African swine fever are of major concern. “It’s a highly infectious and contagious hemorrhagic disease that affects only swine,” said Shere. “There are many strains that range in severity from rapid death to chronic disease, but eventually almost all pigs that contract it will die from it.” African swine fever predominately spreads from feces, but any excretion from a pig that carries the virus including nasal secretions or a cough can infect healthy pigs. “It’s a contact disease pig to pig,” said Shere. “It’s also moved as a fomite. If I get the feces on my shoes, my clothes, or my hands and go from one pig pen that’s infected to one that’s not, that’s how I spread it.” The virus also can be spread by vehicles that have driven through infected soil.

Pigs that eat infected pork can contract the disease too. “It’s not a human health hazard, but uncooked pork could still have the virus. Pigs will eat anything, and that food waste, if it’s fed to pigs, can spread the virus,” said Sherrilyn Wainwright, a senior veterinary epidemiologist/risk analyst for the USDA’s Animal Plant Health Inspection Service who monitors the global spread of African swine fever and other diseases of economic and public health consequences in the U.S.

African swine fever is resilient. The virus can survive in edible products such as chilled meat for at least 15 weeks, in frozen meat for over a year and up to three to six months in processed hams and sausages that have not been cooked or smoked at a high temperature, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Historically, the virus was pretty much confined to the African continent until 2007, when a ship from Africa carrying pork infected with African swine fever entered a port in the country of Georgia. “Uncooked food waste from that ship, including pork, was likely fed to pigs or was scavenged by wild boar that ate the pork,” said Wainwright. “The virus was then introduced into Georgia, Azerbaijan and Armenia.”

From there, African swine fever spread into Russia, Eastern Europe, Western Europe, China and other parts of Asia. “2018 was the widest expansion. Once the virus entered China, it swept through the country and killed millions of pigs,” said Shere. “That’s when everyone started to get nervous.” Since China’s first detection in August 2018, a total of 17 Asian countries and Hong Kong all have reported infections of African swine fever for the first time.

“It continues to move and that’s a concern,” said Shere, noting that the carelessness of people and wild boar are the two main drivers that have spread African swine fever across the world. “Wild boar do not look at boundaries of countries,” said Wainwright. “They can travel across lines and cause infection as they go. In many instances, that is how it is believed the virus moved across Europe.”

An example of how people have transported the infection occurred when African swine fever was introduced in the Czech Republic in 2017 and in Belgium in 2018. “It is believed that African swine fever traveled from Poland to the Czech Republic and Belgium because of humans carrying infected meat and unintentionally discarding it in areas where there were wild boar that ate it,” said Wainwright. “In both countries, the virus only infected wild boar and authorities were able to systematically eradicate it by focusing on a strategic plan to contain the wild boar in the area and depopulate them.” The Czech Republic declared itself free of the disease in April 2019 and Belgium made a similar declaration in the fall of 2020. “These are the only two countries that have successfully eradicated African swine fever in this global outbreak,” said Wainwright.

The Dominican Republic and Haiti are currently the only two countries in the Western Hemisphere that are affected by African swine fever. “We want to eliminate the virus before it travels to other countries and, most importantly, before it gets to the United States,” said Shere, whose agency leads the U.S. government’s effort. “When you consider CBP’s role in protecting us and intercepting infected meat, it’s huge. Without that partnership, it’s like leaving the barn door open and putting the entire population of swine in the United States at risk. What CBP does is very important for us.”

Action plan in place

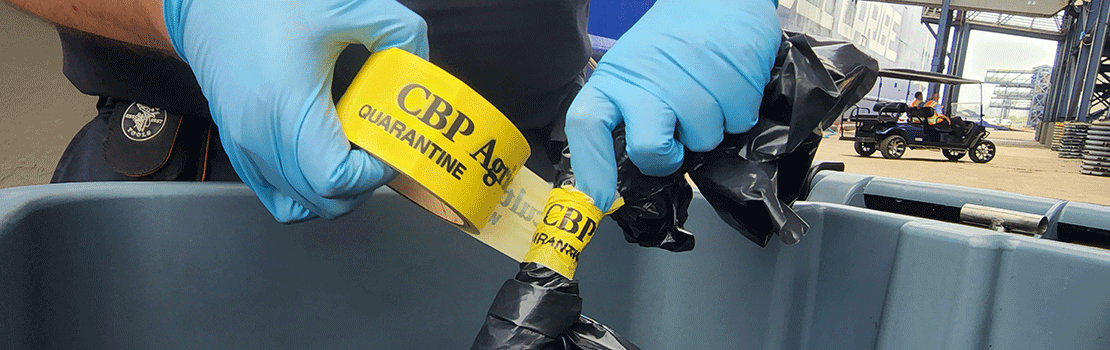

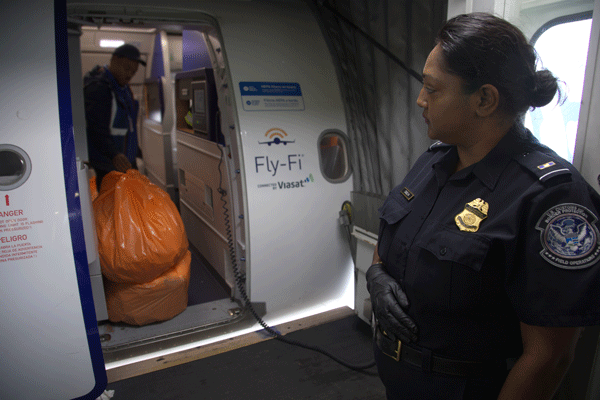

When African swine fever was first detected in the Dominican Republic in July 2021, CBP’s agriculture specialists at John F. Kennedy Airport immediately put an action plan in place to respond to the increasing threat of the virus. The main goal of the plan was to board flights arriving from the Dominican Republic and Haiti to ensure that the regulated garbage was disposed of properly. “Our agriculture specialists who work on our cargo compliance team make sure that the folks who cater and clean the aircraft are doing so in accordance with compliance agreements,” said Paul Gunther, CBP’s deputy chief agriculture specialist at JFK Airport.

“We walk through the cabin and check the seats to make sure there’s no leftover food from the passengers. Many times, we find fruits and vegetables or uneaten sandwiches that may contain pork. We ensure that all of that food gets collected and disposed of in accordance with the regulated garbage regulations,” said Gunther. “All of the trash that comes off of the aircraft has to go into a quarantine compacter. Then the compacter is brought to an incinerator.”

The JFK agriculture specialists monitor 41 kitchens, caterers and garbage haulers that fall under USDA compliance agreements. “At the outbreak of African swine fever in the Dominican Republic, we made a concerted effort to perform outreach to all of the companies that hold compliance agreements,” said Gunther. “We discussed the importance of keeping the regulated garbage safe and making sure the companies followed the stipulations of the agreements,” he said. “Regulated garbage is a major risk factor for introducing animal disease into the United States. We monitor regulated garbage for all animal diseases. We don’t just do this for African swine fever.”

Dedicated agriculture specialists also were added at JFK’s express courier facility. “We knew there was a threat of pork products from African swine fever affected countries coming through express consignment, so in October 2021, we assigned more individuals to inspect a higher volume of packages,” said Gunther. “We were performing exams in the express courier facility on a daily basis, but we didn’t have a dedicated team that went there seven days a week.”

During fiscal year 2021, the agriculture specialists performed 12,500 exams in the express courier facility. In fiscal year 2022, with the addition of the dedicated team, the JFK agriculture specialists surpassed that figure, conducting 12,800 examinations of express courier shipments by mid-May. “Of those exams, we made 1,100 animal product seizures; 133 of them were pork products from African swine fever affected countries,” said Gunther. “In seven months, we seized over 1,000 pounds of prohibited pork products that were destined for multiple locations throughout the country.” The number of inspections increased in 2023 to 47,934 examinations. CBP’s agriculture seizures also increased to 5,531 plant and animal products of which 1,116 were pork products.

Smuggling at seaports

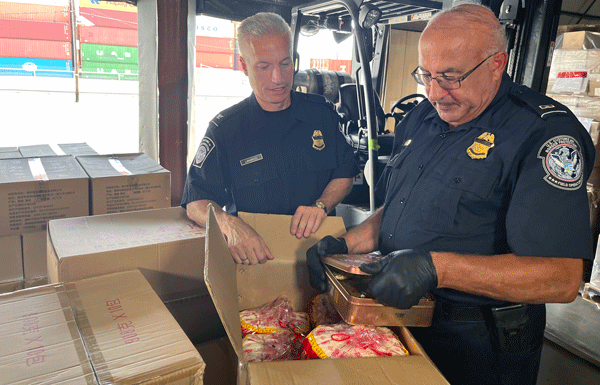

But the largest quantities of prohibited pork products are smuggled in containerized shipments that arrive at seaports. “Smuggling prohibited meat products is nothing new in the maritime environment, but we definitely have seen an increase in the large quantities of animal products attempting to enter the United States, especially pork,” said Peter Wawrzyniak, a CBP supervisory agriculture specialist at the Los Angeles/Long Beach Seaport, the largest seaport in the country. “Most of the products we’re seeing are in e-commerce shipments, which could be anywhere from 1,000 to 3,000 boxes in an 80-foot container.”

Nearly 230,000 pounds of pork-related products were seized at the seaport during fiscal year 2021. The majority of the shipments, more than 90%, are from China and then Southeast Asian countries. “After we target shipments, it’s not uncommon to find that 60% to 80% of the contents are meat products,” said Wawrzyniak. “The trend over the last several years, especially during the last 18 months, has been an increase in unmanifested shipments of prohibited pork and meat products,” explained Wawrzyniak.

For example, in late April 2022, a shipment from China manifested as “plastic parts” was targeted for an agriculture inspection at the Los Angeles/Long Beach Seaport. “The importer had a long history of bringing in prohibited meat products, especially pork, so the shipment hit both CBP’s and USDA’s radar,” said Wawrzyniak.

When the shipment arrived, the CBP agriculture specialists examined the package with USDA’s Smuggling Interdiction and Trade Compliance unit. “The weight of the shipment was enormous,” said Wawrzyniak. “Approximately 8,700 pounds of unmanifested pork were in the shipment along with other prohibited meat products.”

Relying on intelligence

CBP relies on intelligence to stop prohibited shipments. One stunning example at the port of New York/ Newark seaport had impressive results. In October 2021, CBP officers at the port received a tip from industry that several shipments were coming in that included smuggled agriculture goods from China. “In the majority of these cases, the products are clandestinely smuggled in shipments comingled with legitimate merchandise to avoid detection,” said Basil Liakakos, CBP’s agriculture branch chief at the port of New York/Newark.

In this case, the shipments were manifested as shower curtains, but instead the CBP agriculture specialists found 700 boxes of pork sausages in the 40-foot container. “Typically, whatever is manifested on the entry documents is not in the shipment,” Liakakos explained. The pork sausage, which weighed 20,000 pounds, was being shipped to a distribution center in Jersey City, New Jersey, and then ultimately to Flushing, Queens, where New York City’s largest Chinatown is located. The declared value on the shipment was $4,000, considerably less than the $340,000 appraised value.

“This is transnational crime,” said Liakakos. “What we found is individuals are working collectively around the country to bring these imports in whether it’s through our port or L.A.-Long Beach or Houston. They are networks no different than the networks smuggling narcotics or intellectual property rights. It’s a business and it’s a booming business because they’re taking illicit profits and purposely evading paying the duty.”

The entire shipment of prohibited sausages was seized and destroyed, and a new source location was discovered. “We were able to intercept products coming from an African swine fever affected country that could have made it into our swine industry,” said Liakakos. “We do that on a daily basis, but this interception was a large maritime commercial interception that could have caused significant harm to the United States.”

Intercepting prohibited pork

A plethora of prohibited pork products also are intercepted at the port of Cincinnati, the main express courier hub for shipments coming into the country from China and Southeast Asia. “In 2019 and 2020, after African swine fever swept through China and the pandemic hit, we noticed that food products coming from Asia were down in general, but now we’re seeing a lot more pork, which means the risk is higher,” said Barbara Hassan, CBP’s supervisory agriculture specialist at the port of Cincinnati. “Most of the smuggled shipments of pork are from China and Hong Kong, but we are seeing an increase of items arriving now from Vietnam, Korea and Thailand, which are all African swine fever affected countries.”

The Cincinnati agriculture specialists have a range of methods to find the prohibited pork. “CBP policy requires that every package is x-rayed or scanned 100%,” said Hassan. “But through many years of training, our agriculture specialists can actually pick up a box and know if it’s suspicious.” The agriculture specialists also learn how to read Chinese symbols. “Sometimes the packaging will say in English that the ingredient is fish, but we’ll see a symbol of a pig.” The agriculture team also relies on their noses. “You’d be surprised how many times we look over and see someone smelling something. ‘That’s pork. Nope. That’s beef. Nope. That’s chicken,’” said Hassan.

In January 2022, one of the Cincinnati agriculture specialists found a 94-pound pig that arrived in several shipments from Hong Kong. The shipments were manifested as “kitchenware,” but only food products were found in each box. In the first shipment, the agriculture specialist found 15 pounds of pork, in the second, he found 13 pounds of pork, and much to his astonishment, in the last shipment, he found 66 pounds of pork. “Sometimes people will send a small shipment to see if it gets stopped and then they’ll send a larger one,” said Hassan. “If the agriculture specialist had not persisted, he would not have seized the largest shipment. That’s why we need to be very vigilant with our targeting.”

According to Hassan, the agriculture specialist’s suspicions were aroused after he checked the physical locations of where the shipments were being sent. “The first package was sent to an apartment building with stores on the street level,” said Hassan. “The second was sent to an open field next to a freeway in Brownsville, Texas, which was obviously a fictitious address. The third, the largest shipment, was sent to a nail salon at a strip mall in Champaign, Illinois. To my knowledge,” said Hassan, “the shipper has not been found.”

Close to the source

Immediately after African swine fever was reported in the Dominican Republic, the port of San Juan in Puerto Rico took action. “We are in a unique position being so close to the source of the outbreak. The majority of the passengers that we receive and process are from the Dominican Republic, so it is crucial that we focus and shift our resources to prevent pork products from coming into the United States,” said Keyvan Santiago, CBP’s agriculture branch chief for the area port of San Juan. “Puerto Rico is only 80 miles from the Dominican Republic and we have 4-5 direct flights arriving from there daily.”

As part of its strategy, the port increased the number of agriculture specialists at the Luis Muñoz Marín International Airport in San Juan, Puerto Rico’s only international commercial airport. With the additional staffing, surveillance was increased as well as the number of passengers referred for more in-depth, secondary inspections.

From July 2021 through mid-June 2024, CBP processed more than 128,840 passengers arriving at the San Juan airport from the Dominican Republic. “It doesn’t compare to the volume of passengers that New York, Newark, Chicago, or Miami receive, but due to the fact that we’re so close to the island and have so many Dominicans living in Puerto Rico, who want specific cultural items from their native land, the level of risk here is much higher,” said Santiago. “That’s why we have to remain vigilant and maintain the level of scrutiny that we do when we perform our job at the ports of entry. It’s imperative.”

Ferryboats from the Dominican Republic also arrive in San Juan three times a week. “We x-ray 100% of the bags coming off the boats,” said Santiago. “We find pork rinds; fried pork; pasteles, which are little patties with cooked meat inside; we also find gigantic Dominican sausages and other pork meat.” The ferryboats also carry vehicles contaminated with soil. “The soil can carry a lot of diseases that we don’t want in the United States, so we do inspections of the vehicles,” he said. CBP officers and agriculture specialists board most of the boats to check the regulated garbage procedures. “All of the garbage on the boats must remain inside the boats,” said Santiago. “We cannot allow it to get offloaded here in Puerto Rico or travel to the U.S. mainland.”

Illegal boat landings called “yolas” are another potential pathway for the disease. The yolas, which travel from the Dominican Republic and Haiti, are rudimentary fishing boats packed with migrants. “They drop provisions in the boats and try to make it into the coastal areas of Puerto Rico,” said Santiago. “Whatever they bring may present a risk of contamination.”

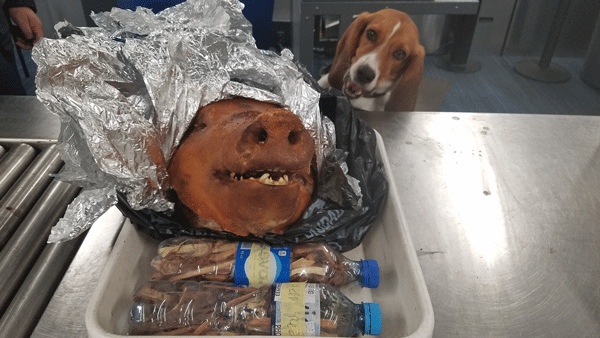

A beagle’s nose

One of CBP’s most powerful tools in keeping African swine fever out of the U.S. is the Beagle Brigade. The beagles, who work at all the major international airports in the U.S. and Toronto, search for inadmissible items including fruits, vegetables, meats, flowers and plants. “We don’t want certain commodities to come into the country that have the potential to bring plant and animal diseases or pests, which could become invasive,” said Charron Byndloss, the regional agriculture canine advisor for CBP’s Seattle, San Francisco, and Portland field offices.

CBP currently has 160 active beagles, but the number is increasing. “The agency would like to double the number of dogs in the field. African swine fever is one of the main reasons,” said Byndloss. The beagles are initially trained to find five basic scents – apples, mangos, citrus, beef and pork. “Sometimes these food products are hidden in suitcases, purses, baby carriers, strollers or on a person. Most people are bringing these products accidentally, but some people are trying to sneak them in.” she said.

Once a dog smells one of the odors, it sits to alert its handler. “The beagle can actually do this job faster than a person,” said Byndloss. “People take time to look through bags. The beagle smells the odor, identifies it and moves on to find the next scent. So the dogs can clear a lot more baggage and a lot more cargo than their handlers can.”

CBP also created a mobile app feature for travelers who are bringing items that may require an inspection. This could include examining footwear worn while visiting a farm overseas, checking biological research materials, or an inspection of a pet dog, cat, or bird. The feature, which is part of the agency’s CBP One™ application for mobile devices, enables travelers to initiate a request for an inspection up to 72 hours prior to their flight’s arrival at a U.S. port of entry “We designed the feature with the idea of speeding up the process, to make it easier for travelers,” said Suzette Kelly, CBP’s director of agriculture safeguarding and risk management. “We are looking to the public to partner with us to keep African swine fever out of the country. A lot of people don’t realize the dangers, so we want to make sure they are aware.”

Although developing a vaccine for African swine fever has been elusive for decades, it appears one is on the horizon. “USDA’s Agricultural Research Service has developed several different vaccine candidates. One of them is being developed under a joint agreement with a company in Vietnam,” said Wagstrom from the National Pork Producers Council. “It has been field tested in Vietnam and it’s now reached full approval for commercial production,” she said. “The research is promising. It looks like maybe for the first time we’re seeing a vaccine that is providing some protection. But it’s not a silver bullet,” said Wagstrom. “So having CBP preventing an entry of African swine fever into the nation is our best hope for continuing business as usual.”

More information

www.cbp.gov