Measuring cross-border e-Commerce: how adopting an ICT-driven approach can facilitate greater accuracy

31 October 2024

By Kumar Aseem Vaibhav and Kaushik Thinnaneri Ganesan, Express Cargo Clearance System, Indian Revenue ServiceThis article explores three approaches that could facilitate a more accurate, practical and tenable measurement of the size and value of cross-border e-commerce, enabling governments to obtain a clearer picture of its actual contribution to the economy.

Cross-border e-commerce has emerged as one of the key facilitators of international trade and as a key driver of economic growth in a number of countries, as can be seen from the growth in volume of parcels transported through both postal services and express cargo. In India, e-commerce holds immense importance, providing a platform for the micro, small and medium enterprises (MSME) industry by not only reducing entry barriers but also opening up newer markets hitherto closed to the smaller players.

This being said, accurately measuring the size and value of cross-border e-commerce transactions remains a challenge that needs to be addressed. Indeed, an accurate measurement of the value of e-commerce would assist governments to better leverage the benefits of this sector, assess its impact on the economy, and ultimately promote informed decision making, as highlighted in Standard 15 of the WCO Framework of Standards on Cross-Border E-Commerce.

“Customs administrations should work with relevant government agencies in close cooperation with E-Commerce stakeholders to accurately capture, measure, analyse and publish cross-border E-Commerce statistics in accordance with international statistical standards and national policy, for informed decision making.”

Standard 15: Mechanism of Measurement, WCO Framework of Standards on Cross-Border E-Commerce

One of the reasons for the absence of a global method is the lack of a specific, internationally agreed definition.

The Framework of Standards characterizes cross-border e-commerce as follows:

- Online ordering, sale, communication and, if applicable, payment,

- Cross-border transactions/shipments,

- Physical (tangible) goods, and

- Destined to consumer/buyer (commercial and non-commercial).

However, there is a wide variety of definitions of e-Commerce, both nationally and internationally and, moreover, an absence of clear-cut mechanisms for measuring it, including from an information and communication technologies (ICT) perspective.

Survey-based approaches

Most of the methods developed by international organizations so far are based on surveys. In 2023 the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) published a document entitled Measuring the value of e-Commerce. This defines e-commerce as referring “to transactions in which goods or services are ordered over a computer network (e.g., over the Internet)”.

To respond to countries’ needs related to measuring the value of e-commerce, UNCTAD recommends conducting “business surveys asking about e-commerce sales, household surveys asking about e-commerce purchases (and sometimes sales)”, using “official statistics on online retail sales (which represent only a small portion of business-to-consumer e-commerce)”, and analysing “sources such as payment card transactions data or parcel post volumes.”

The document also addresses measuring the value of e-Commerce and highlights two approaches to gathering data:

- Direct approach: Businesses are asked to report a monetary value for their e-commerce sales. In most cases, these figures are requested rounded to the nearest whole currency unit (e.g., dollar), but in some questionnaires respondents are asked to round to the nearest thousand currency units.

- Share approach: This approach involves asking respondents to provide a monetary value for a relevant total, such as annual turnover or sales revenue, and also to give the percentage share of that total arising from e-commerce sales. Together, these items are used to derive an estimate of the responding enterprise’s e-commerce revenues.

This methodology is dependent on the responses from stakeholders such as businesses, thereby placing an onus on the surveyors to ensure an acceptable degree of accuracy in the survey method. Not only does it rely on the responses submitted by the respondents, it also involves extrapolation of the numbers based on a sample set of respondents, both of which leave ample room for dilution of data quality.

Survey-based approaches are also the main methods described in The Handbook on Measuring Digital Trade, which was born in 2023 out of a collaborative effort between the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), UNCTAD and the World Trade Organization (WTO).

Proposals for accurate measuring

Today many Customs administrations have automated a substantial portion of their processes, thanks not only to the development of technologies but also to the substantial outreach efforts deployed by the WCO. Be it ASYCUDA or custom-made software applications, many Customs processes, such as the filing of manifests or the submission of declarations, can be carried out electronically.

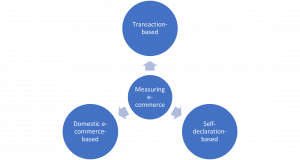

In such a scenario, three broad streams of methods for measuring cross-border e-commerce are worth considering. These are discussed in detail below, along with advantages and disadvantages of each approach.

Transaction-based approach

In the transaction-based approach, every Customs declaration, be it import or export, is classified as either pertaining to e-commerce or not, based on a set of rules configured in the IT system. The rules would have to be driven by how the terms “cross-border e-commerce” or “e-commerce” are defined in the country’s legislation. For instance, the movement of goods from a business to a government entity transported via courier or post operator may be considered e-commerce.

Advantages: This approach may guarantee the highest degree of accuracy in measuring e-Commerce data, since it is entirely system driven. Any change in policy can also be dealt at the system level.

Disadvantages: On the downside, this approach would entail classifying every transaction based on a multitude of factors, including the identification of both buyer and seller (i.e. importer and exporter) as a Business, Consumer, Government, etc. More importantly, it would require first ensuring that the transaction took place through an online platform, for example by asking the importer/exporter to declare that this was the case. In addition to creating a new set of data fields or additional properties for existing data fields, this approach is also likely to add overheads to the system and affect the speed of processing every declaration in the system.

Self-declaration-based approach

The self-declaration approach is an improvement upon the survey approach in the sense that the importer/exporter is asked to indicate in the Customs declaration that the transaction fits in the definition of e-commerce by ticking a simple checkbox, without being asked to provide more information. Thus, while this approach relies on a declaration made by the importer/exporter, there would be no need for a survey or extrapolation, since every transaction would be classified as either being e-commerce or not.

Advantages: This approach would entail minimal additional developmental load on the application, since all it requires is an additional checkbox, which could be stored in the database as a single additional data field. Customs administrations may consider making this a mandatory field if the measurement of e-commerce data is of vital importance.

Disadvantages: This approach has two major disadvantages. First, it would require the Customs administration to issue specific guidelines on when an import/export transaction can be categorized as “e-commerce”. Second, ensuring the veracity of the declaration would be difficult, as there would be no additional information to prove that the transaction fits the definition of e-commerce.

Domestic e-commerce laws-based approach

The third approach proposes making use of regulations which already require economic operators to declare their activity as “e-commerce”. For instance, in India, as part of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) reform that was rolled out in 2017, the term “electronic commerce operator” was explicitly defined and companies which registered under the GST system were required to indicate whether they were an e-commerce operator. If the Customs IT system were connected to the GST system, any import/export transaction made by a company registered as an e-commerce operator would automatically be classified as an “e-commerce transaction”. One key challenge that could arise is the treatment of importers/exporters that are not registered in any government database. For such entities, a separate provision could be created on how to handle such transactions.

Advantages: This approach offers significant advantages. First, since the classification is carried out at the entity level, minimal coding would be required in the Customs application used for filing import/export declarations, thereby not impacting on the processing speed. Second, the accuracy of data would be ensured, since it is a completely system-driven mechanism. Third, and most important, this approach would ensure harmonization between the legal definitions of domestic and cross-border e-commerce. This would greatly contribute to ensuring that economic policies are evidence-based. Furthermore, it would also help bridge the gap between a country’s domestic and international supply chain, and provide better opportunities for the government to formulate policies in this area.

Disadvantages – The only minor disadvantage of this approach is, as mentioned earlier, the need to address companies that are not registered domestically but are involved in the import and export of goods. Interestingly, this may actually encourage countries to treat such companies in the same way as domestic business entities.

Conclusion

The intention behind this article was to explore approaches to measuring e-commerce, beyond those based on surveys. The approaches outlined above are by no means ideal or perfect solutions for measuring cross-border e-commerce. But they are an attempt at improving the existing measurement approaches and arriving at specific ICT-driven measurements for e-commerce. They would also help establish linkages between domestic and cross-border e-commerce, as a large share of online transactions that are perceived as domestic by consumers involve a cross-border element. This, in turn, would provide a clearer picture of the actual contribution of e-commerce to the country’s gross domestic product and employment and, thereby, the country’s overall economic development.

More information

kumaraseem.vaibhav@gov.in

kaushik.tg@gov.in