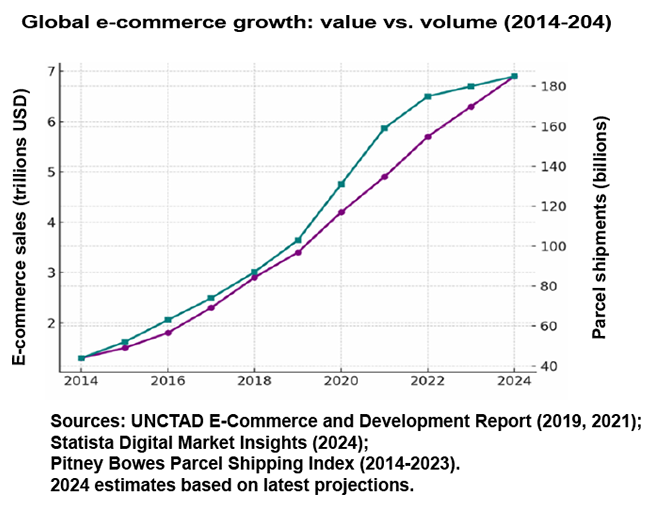

In less than a decade, e-commerce has redrawn the global trade landscape. Once a marginal channel for cross-border sales, it is now the backbone of international consumer trade. Between 2014 and 2024, global retail e-commerce sales expanded from around USD 1.3 trillion to nearly USD 7 trillion. Parcel volumes rose in tandem, climbing from roughly 44 billion in 2014 to an estimated 185 billion in 2024. This fourfold increase in flows has reshaped supply chains, consumer behaviour and the workload of Customs administrations.

The impact on border management has been profound. Customs administrations, already under pressure, now face the task of controlling flows measured not in containers but in millions of parcels per day, moving from millions of businesses to millions of individuals.

Only a few years ago, most countries applied a de minimis regime that allowed low-value imports to enter duty- and tax-free, sometimes with limits on the value of individual transactions and the total annual value of cross-border e-commerce purchases per domestic consumer. There was also a reporting threshold – the value above which a full Customs declaration is required.

Today, perceptions of de minimis have shifted from seeing it as a facilitation tool to viewing it as a contested loophole. De minimis regimes were designed to spare administrations from processing minor transactions and to keep revenue collection cost-effective. Yet what began as a sensible facilitation measure has, with the boom in e-commerce, come to be seen as a source of revenue loss and a facilitator of illicit trade.

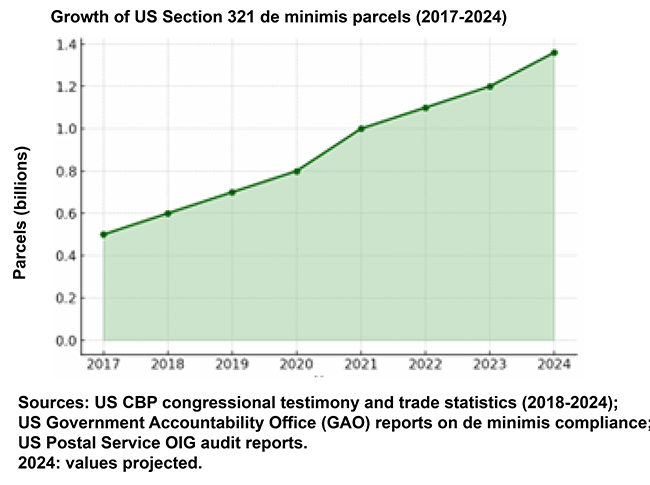

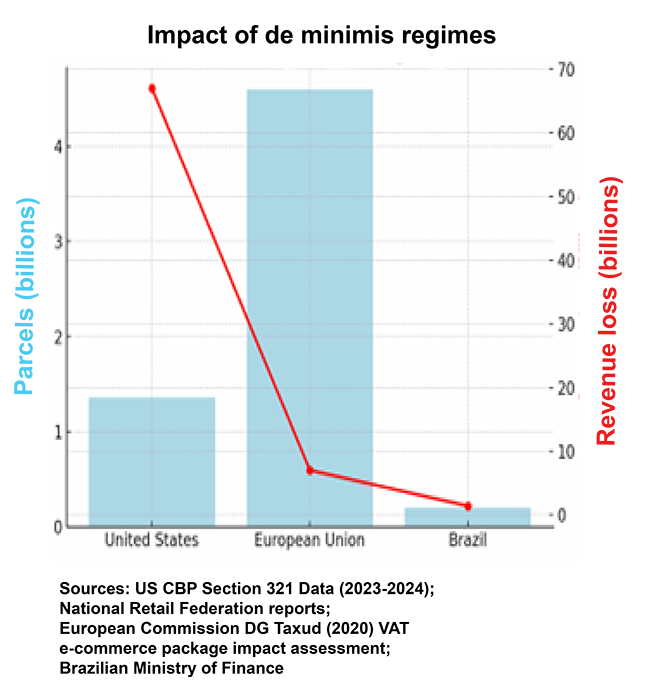

The United States provides a striking example. In fiscal year 2024, 1.36 billion parcels entered under the Section 321 de minimis threshold – almost four million shipments per day. Retail associations estimate that the value of these imports exceeded USD 67 billion in 2023. Almost all entered without duty or tax, effectively granting foreign sellers an 8-10% price advantage over domestic retailers, who are required to collect sales taxes and pay import duties.

Europe has faced a similar challenge. Before the reform of July 2021, the VAT exemption for parcels valued under EUR 22 caused annual tax losses estimated at around EUR 7 billion. Worse still, the majority of undervalued consignments clustered just below the threshold – clear evidence that traders were deliberately structuring shipments to avoid tax.

Brazil has encountered the same pattern: industry associations there estimated that nearly BRL 7 billion (USD 1.4 billion) in annual sales were being lost to duty-free cross-border platforms. Increasing numbers of seizures of illicit and substandard goods were also reported, while risk management capacities suffered from low data requirements and poor data quality.

It is therefore unsurprising that governments are reversing course. In August 2025, the United States abolished its de minimis exemption altogether. The European Union had already done so in 2021 for VAT, introducing the Import One-Stop Shop (IOSS). Brazil recently introduced a 20% federal tax on purchases of up to USD 50 for companies certified under the Programa Remessa Conforme, Brazil’s voluntary compliance programme open to national and foreign companies using e-commerce platforms, websites or digital tools to sell their products.

India went as far as banning Shein outright before permitting its re-entry only through a partnership with a domestic company. The rollback of de minimis is thus about more than revenue or risk: it reflects domestic politics and industrial competitiveness. Retailers argue that foreign sellers are given an unfair advantage, industries claim their tariff protections are being eroded, and policymakers insist that consumers buying online from abroad should not enjoy a fiscal privilege denied to those purchasing at home.

What was once an administrative convenience has become a point of contention at the intersection of trade facilitation, fiscal policy and industrial strategy.

Platforms are now under additional scrutiny: as parcel thresholds are tightened, they are being asked to shoulder new compliance responsibilities. Around the world, governments have moved to treat digital marketplaces as gatekeepers.

Indonesia’s decision in 2023 to ban TikTok Shop transactions, later permitting its return under strict regulation, was a clear signal that platforms must separate social media functions from regulated commerce. France’s temporary de-listing of Wish from app stores in 2021, lifted only after significant improvements in product safety, demonstrated that regulators are willing to sanction non-compliance at the distribution layer.

The European Union has gone further, applying its new Digital Services Act to open formal proceedings against Temu in 2024, focusing on the traceability of sellers and the responsibility of platforms to manage systemic risks. In India, the ban and conditional return of Shein underscored the same principle: market access is no longer unconditional but tied to commitments on compliance, safety and – in Shein’s case – local production. These cases illustrate a global shift. Platforms are no longer neutral intermediaries; they are expected to validate sellers, remove unsafe goods, collect taxes and cooperate directly with Customs.

Postal services remain the weakest link. While platforms are adapting, the postal channel continues to struggle with the demands of the e-commerce era. Despite legal mandates such as the US STOP Act and the EU’s Import Control System 2 (ICS2), millions of parcels still arrive without advance electronic data, or with data of such poor quality that Customs cannot act on it. US audits found that, between 2019 and 2021, 75 million packages entered the country with incorrect routing information, leaving Customs unable to intercept flagged consignments at the correct port of entry.

Even where data is transmitted, its quality is often poor. Descriptions such as “gift” or “clothes” are of little use to automated risk engines, and fewer than 60% of addresses in one US audit matched domestic postal standards precisely. Critical fields such as HS codes or SKU-level details are frequently left blank. The continued reliance on paper CN22 and CN23 Customs forms – handwritten, inconsistent and optional in their inclusion of HS codes – only exacerbates the problem.

By contrast, the UPU-WCO electronic messaging standards (ITMATT/CUSITM) require structured, machine-readable data, including HS-6 codes, standardized addresses, unique identifiers and links to dispatch and receptacle data. From September 2025, HS-6 codes will be mandatory for commercial items for all countries that require them. In short, CN22/23 forms were designed for a manual postal era, whereas ITMATT was built for a digital one. Customs can no longer rely on paper; structured advance data has become indispensable.

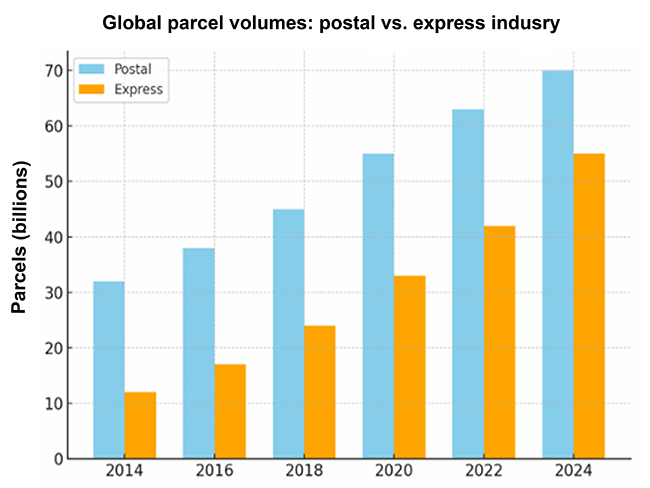

The operational stakes are high. Postal services remain the largest channel for low-value parcels, handling roughly 70 billion consignments in 2024. Yet the express industry, which processed 55 billion parcels in the same year, is catching up fast and has generally been quicker to integrate robust data and compliance systems. The result is a bifurcated landscape: express carriers are increasingly seen as being data-rich and reliable partners, while postal flows are viewed as being risky, opaque and in urgent need of reform.

As parcel flows increase, so too does the complexity of risk. Counterfeiters have embraced small consignments as a means of evading detection, flooding markets with unsafe toys, cosmetics and electronics. Narcotics traffickers exploit the same channel; a single envelope can conceal enough fentanyl to cause multiple fatalities. Fraud is also widespread: systematic undervaluation, split shipments designed to remain below thresholds, and falsified sender or receiver identities all distort revenue and undermine targeting models.

Faced with these challenges, Customs administrations are moving the border to the data. Systems such as the EU’s ICS2 extend pre-arrival data requirements across all transport modes, giving Customs the ability to identify high-risk parcels before they even leave the country of origin. Collect-at-checkout models, exemplified by EU’s voluntary Import One-Stop Shop (IOSS) scheme and Brazil’s Remessa Conforme programme, align incentives by making platforms responsible for tax collection and data transmission. Seller identity verification and product safety obligations are being reinforced not only through Customs channels but also via horizontal regulatory frameworks such as the EU’s Digital Services Act.

At the operational level, Customs administrations are investing in risk models tailored to small consignments, non-intrusive inspection technologies optimized for high throughput and cooperation with postal operators to close compliance gaps. The World Customs Organization and the Universal Postal Union continue to provide guidance and standards, but national enforcement remains the decisive factor.

There is an urgent need to move from declarations to datasets. The age of de minimis as a facilitation tool is ending. What was once a means of simplifying border management has become a contested loophole at the centre of debates on fiscal fairness, industrial policy and consumer safety. The new frontier is not about value thresholds, but about data. Jurisdictions that move swiftly to secure structured, early access to electronic data, that hold platforms accountable as compliance partners, and that offer facilitation to those who comply will keep their borders functioning as points of passage. Those that do not risk allowing small parcels to become a large-scale compliance loophole – with costs measured not only in lost revenue, but also in consumer safety, industrial competitiveness and public trust.