Switzerland addresses the traffic in cultural goods

28 June 2016

By Professor Jean-Robert Gisler, Federal Office of Police, SwitzerlandThe Swiss art market, being one of the largest in the world, inevitably attracts objects of dubious provenance. Some of these stolen or plundered objects not sold directly on the Swiss market are held in Switzerland pending their insertion in the legal distribution system, whether in Switzerland or elsewhere.

One of the reasons why Switzerland is a destination and transit country for cultural goods is that for many years it has offered storage and trading facilities which helped to sustain not only the substantial local market, but also, above all, the international market.

During the 1980s and the 1990s, Switzerland was viewed by the world as a hub for international trafficking in cultural goods. However, when the spotlight was shone on several major cases involving international traffickers, this helped to raise the awareness of the Swiss authorities, bringing about the adoption of a new legal framework aimed at regulating, in particular, the ‘exceptional’ Customs areas known as free ports and open Customs warehouses.

1970 UNESCO Convention

For a long time, it was the extreme laxity of its legislation that made Switzerland attractive. After a long gestation period the situation changed, both legally and concretely, on 1 June 2005, with the entry into force of the ‘Cultural Property Transfer Act’ (CPTA).

The CPTA constitutes the implementation, at Swiss national level, of the Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property, adopted by the United Nations Educational, Social and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in 1970.

The CPTA regulates the importation of cultural property into Switzerland, its transit and exportation, as well as the return of cultural property located in Switzerland. It also establishes measures to combat the illicit transfer of cultural property.

Through the CPTA, the Swiss Confederation hopes to make a contribution to the maintenance and protection of mankind’s cultural heritage, and prevent the theft, looting, and illicit import and export of cultural property from museums and similar institutions.

The Act also provides for a series of measures aimed at:

- promoting intercultural dialogue and sustainable exchange;

- protecting Swiss cultural heritage (inventory and provisions regulating the export of cultural property belonging to the Confederation or the Cantons);

- contributing to the protection of the cultural heritage of other States (import of cultural property into Switzerland and bilateral agreements);

- promoting international exchanges between museums (restitution guarantee for museums);

- ensuring due diligence is carried out on the art trade and the auction business.

The introduction of the CPTA brought about a significant change in the practices of suppliers, sellers and buyers, whose relationships and positions have evolved. Although they were extremely reticent during the CPTA consultation phase, the actors in the art world have adjusted well. Having feared for the very existence of Switzerland’s art market during the discussions which preceded the adoption of the Act, they now recognize that business has not declined, and that the image of their business has been enhanced.

The obligation to take control of transactions, and the introduction of safeguards designed to curtail illicit operations enabled the art world, as a whole, to attain greater respectability. Nevertheless, for this new legislation to be even more effective, it needed to be supplemented by developments in the Customs field.

Customs warehouses

There are two types of Customs warehouses in Switzerland: duty-free warehouses; and open Customs warehouses (OCWs). Whereas the former are, in principle, available to anyone for the storage of goods under the surveillance of the Customs authorities, the latter are for private use, and do not incorporate a Customs office.

These two types of warehouses can be used, in particular, to store goods under suspension of Customs duties and value-added tax (VAT) pending their final importation into the country of destination. Over the years, this historical function of Customs warehouses has evolved to encompass the storage of valuables, including cultural goods in particular. Thus, works of art are stored in these warehouses under the best possible conditions, while they wait to change hands.

The interest in contemporary art and the need for secure storage facilities go some way towards explaining this development, but there are other factors: the diversification of private investors’ portfolios, especially in the aftermath of the financial crisis; tax optimization strategies in the area of asset and wealth management; the development of ‘art banking’ (an art advisory service developed by the banks); and the development of investment funds and hedge funds that invest in art.

Thus, in recent years, works of art have become financial assets like any other, and transactions can be concluded independently of the physical location of the work of art. This situation has considerably increased the demand for secure storage, preferably outside the tax laws of a given country, enabling works of art to change hands as financial transactions may dictate, without physically changing location.

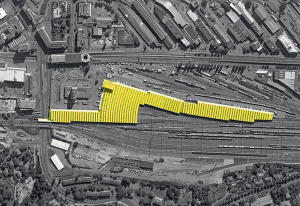

The OCWs, whose primary function is the temporary storage of large consignments of goods in transit – for example, garments while being labelled – are sometimes used for high-value goods. However, although their number has increased rapidly in recent years, they have yet to outrank the now ultra-secure free ports in this respect; especially the one in Geneva which recently opened a new building on its ‘territory,’ with a floor area of 10,400 m2, devoted entirely to the warehousing of works of art.

As one can imagine, these warehouses have also been used to store illicit goods and to circumvent, notably, the requirements of the CPTA. Given such activities, the Swiss legislature had to draw up a new legal framework to regulate, in particular, these ‘exceptional’ Customs areas, namely free ports and OCWs.

New Customs Act

The new Customs legislation, i.e., the Customs Act which was adopted by the Swiss Parliament in 2005 and entered into force in 2007, updated Swiss law to reflect modern Customs requirements, especially in the area of combatting illicit trafficking. It replaced legislation which dated back to 1925, and which had not been revised frequently.

The provisions concerning OCWs (CA, Articles 50 to 57) and free ports (CA, Articles 62 to 67) fall into two different Chapters, but some of them are similar. The major changes introduced by this new legislation, insofar as free ports and OCWs are concerned, include the following:

- The introduction of Customs warehousing as a new Customs regime, encompassing OCWs which are distinct from free ports. The Customs warehouse is defined as a place in the Customs territory which is authorized by the Customs administration and placed under Customs supervision, and in which goods can be stored under conditions laid down by Customs. For OCWs, this procedure involves, among other things, the removal of import duties and the non-application of commercial policy measures, the identification of the goods, and random checks on compliance with the conditions and charges stipulated in the authorization;

- A new definition of free ports, now known as ‘duty-free warehouses.’ Free ports are no longer defined as being foreign Customs territories, and as a result they no longer have ‘extra-territorial’ status which precludes any inspections on their premises. The legislature has taken care to define them precisely: duty-free warehouses are parts of the Customs territory, or premises located on that territory, which are under Customs supervision, are separate from the rest of the Customs territory, and in which goods which are not in free circulation can be stored. Goods placed under an export procedure can be stored there if, after leaving the warehouse, they are actually exported. The stored goods are not subject to import duties or commercial policy measures;

- An obligation to keep an inventory of so-called sensitive goods (including, in particular, art objects and cultural goods) in free ports, and all goods in OCWs.

Warehouse operator and depositor

Both the warehouse operator (who runs the warehouse) and the depositor (the person who stores goods in the warehouse and who is bound by the declaration used to place them under the warehousing procedure, or one to whom that person’s rights and obligations have been transferred) are recognized under the free port and OCW provisions, with an identical definition and similar obligations.

Anyone who operates a Customs warehouse requires authorization from Swiss Customs. Authorization is granted on condition that the requesting party is domiciled in Switzerland and undertakes to operate the warehouse in compliance with requirements, and that Customs supervision and control will not entail disproportionately high administrative costs. There may be charges associated with the authorization, and it may exclude the storage of certain high-risk goods, or specify that high-risk goods must be stored in special premises.

Warehouse operators and depositors have fewer obligations to Customs in a free port than in an OCW: no financial security is payable; and the inventory is confined to sensitive goods only. The operator of a free port has no responsibility in respect of the goods stored as the responsibility lies with each depositor.

Inventory requirement for cultural goods

There is no doubt that the maintenance of an inventory is key to the proper functioning of the duty-free warehouse and OCW regime. Warehouse operators must draw up lists indicating the value of the object and where it has come from, as well as the identity of the person entitled to dispose of it; also, a certificate of origin must be appended. Customs may request access and conduct controls at any time.

In duty-free warehouses, the inventory requirement is confined to sensitive goods only. The warehouse operator must maintain an inventory of all sensitive goods held in the warehouse, in the form prescribed by Customs, and cultural goods are rightly regarded as sensitive goods (in some cases the depositor may be required to fulfil this obligation). The warehouse operator is also responsible for ensuring that during their stay, goods are not removed without Customs supervision.

The warehouse operator is also required to ensure that the obligations arising out of the warehousing of the goods are fulfilled. The status of the goods changes (i) at the moment when they leave the warehouse, because at that time they are placed under an authorized Customs procedure for entry into the Customs territory or for import, or (ii) when they are declared under the transit procedure and exported.

Implementation

The Federal Customs Administration (FCA) is responsible not only for granting authorizations to warehouse operators and ensuring that the operating conditions are complied with, but also for ensuring compliance with the requirements laid down by other, non-Customs legislation, including the CPTA which assigns the task of controlling the transfer of cultural property at the border to Customs.

Thus, Customs is required to control the transfer of cultural property at the border, including, in particular, import, export or transit declarations (CPTA Article 19). It may request support or expert advice from the Federal Office of Culture (FOC), which is the body responsible for the implementation of the CPTA, or indeed from the Federal Office of Police in respect of these declarations, for example in order to determine the provenance of a suspect cultural object (theft, looting, false declaration, incorrect or fraudulent export permit, etc.

Customs is not, however, in a position to check all declarations relating to cultural property. By way of illustration, it was reported in a publication from 2012 that the ‘Genève-Routes’ Customs office, which is responsible for the free port at La Praille, deals with 250 declarations a month, on average, for the warehousing of cultural goods. Customs’ interventions are therefore based on risk analysis.

The FOC informs Customs of the risks identified at the international level. It does so based on announcements made by organizations engaged in combatting the illicit trafficking of cultural property at the international level, i.e., the International Council of Museums (ICOM), UNESCO, and INTERPOL.

Inversely, Customs offices notify the FOC of cases they discover in the field; it is then the FOC’s job to determine whether the cases notified by Customs are suspicious and warrant criminal proceedings, which are a matter for the Public Prosecutor’s Office of the Canton concerned. Where there are suspicions about the nature of an item of cultural property, it is analysed by an expert to determine where it has come from, thereby enabling it to be returned.

It is also worth noting that the penalties for CPTA infringements are severe: if the offence is committed through negligence, the penalty is a fine of up to 20,000 Swiss Francs (around 22,000 US dollars). If the offender has acted in a professional capacity, the penalty is a prison sentence of up to two years, or a fine of up to 200,000 Swiss Francs.

The Customs authorities have been conducting sporadic and targeted controls since 2011, warehouse operators having been granted time to draw up their inventories. These initial controls have revealed the presence of objects which have been stored for many years, and which in some cases are even found to be unclaimed assets. Certain objects, particularly from Egypt, Libya, Syria and Turkey, are the subject of ‘requests for return’ by the countries of origin concerned.

The Federal Audit Office has looked into the question of how to increase the effectiveness of the controls conducted by Customs. In a report published on 28 January 2014 (www.efk.admin.ch), it made eight recommendations:

- The first recommendation is directed at the Swiss Federal Council, as it involves devising a strategy for the development of Customs warehouses;

- The other recommendations are for the FCA, and are aimed at enhancing the effectiveness of Customs activities in relation to Customs warehouses, with regard to the operating permits and the controls to be conducted.

Another challenge

Switzerland has adapted its Customs provisions and addressed the implementation issues. It also responded promptly in applying the UN embargos on the importation of cultural property from conflict zones (Iraq in 2003, Syria in 2014). Can it now put its dubious past behind it?

This is an important point to reflect on. The new provisions of the Ordinance implementing the Customs Act were introduced on 18 November 2015, i.e., 25 years after this issue was first raised in academic circles, and then picked up by cultural associations and groups. So, it has taken time for Switzerland to rid itself of its bad reputation.

Legislative progress was possible only following a change in attitude, to which several actors contributed. The art market, which is an important part of the Swiss economy, needed to act under new rules and abandon the ‘blind alley’ of protecting and concealing the theft and pillage of archaeological cultural property, in particular.

However, there are other projects awaiting attention, including the ratification of the 1995 UNIDROIT Convention on Stolen or Illegally Exported Cultural Objects. This instrument supplements the 1970 UNESCO Convention, which has a limited sphere of action because it deals only with the restitution of cultural property stolen from museums and similar institutions.

The UNIDROIT Convention, a private-law legislative document in whose development Swiss specialists played a major part, has not yet found favour with the Swiss Parliament. This is doubtless the next challenge to be addressed by Switzerland, at the national level, in the fight against the trafficking in cultural goods.

More information

www.efk.admin.ch

ARCHEO is a communication tool developed to facilitate the exchange of information amongst enforcement authorities, national agencies and international organizations engaged in the protection of cultural heritage. The platform is accessible only to a closed user group, and information transmitted via the tool is encrypted and secured.

ARCHEO aims to:

- Enable the exchange of best practices

- Provide training materials, identification guides, manuals and other relevant background information

- Exchange information on seizures

- Establish discussion forums

- Link enforcement officials with experts in order to facilitate the determination of the nature of the artefacts when confronted with a suspicious transaction

More information

archeo@wcoomd.org