More integration needed to combat transit fraud

15 October 2017

By Giovanni Kessler, Director General, European Anti-Fraud Office, European CommissionWhen it comes to Customs, Europe is at a turning point. In a globalized and fast-paced world, where trade is becoming increasingly liberalized, the role of Customs is changing. Governments around the world are increasingly emphasizing the removal of barriers and the creation of a seamless flow of goods, services and people. This is a key factor of economic growth, and leads to enhanced trade and more global investment.

At the same time, the increased pressure for more efficient, rapid and open movement of goods coincides with heightened demands for more secure passenger and cargo identification than ever before.

Just to give you an idea of the scale we are talking about, in the context of the European Customs Union, Customs officials are on duty at the 400 international airports in the European Union (EU), across its 10,000 kilometre-long eastern land border, and in many large ports. Overall, roughly 270 million Customs declarations are processed annually for more than 3,400 billion euro-worth of products that are imported into or exported from the EU.

With such massive amounts of products entering and circulating the EU at every moment, several Customs procedures, such as transit procedures, for example, provide for the temporary suspension of duties and taxes, allowing importers to clear their goods at the Customs point of their choice, rather than at the point of entry into the Customs territory.

In effect, as Customs fees are set and there is no variation among EU Member States, what importers are actually choosing is which national Customs service they would like to deal with. However, the choice, in itself, is perfectly legal and valid.

Fraudsters hijack transit procedures

In its investigations, the European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF) has uncovered that the transit procedure has been extensively utilized by fraudsters in order to get away with underdeclaring goods, thereby prejudicing the EU budget by billions of euros.

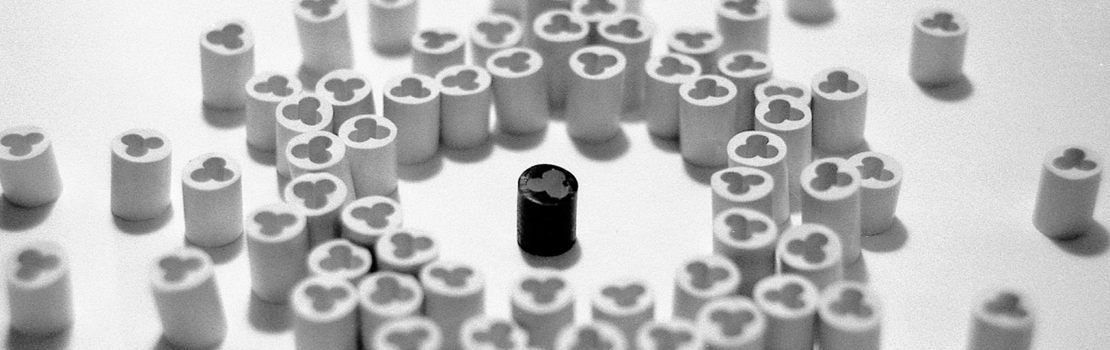

This was the focus of a large OLAF investigation concluded in 2016. OLAF investigators and analysts identified a fraud pattern employed by international organized crime groups who scouted ports in the EU with the weakest controls, in order to get away with declaring falsely low values for textiles and footwear imported from China.

Our investigation revealed that the single most significant hub for this fraudulent traffic was in place in an EU Member State we will call Country Y. The goods, however, did not arrive directly at two of its busiest ports. Typically, they would arrive in containers on vessels, which would enter Europe through other European ports. The containers, considered in transit, would then be placed on lorries, and taken for Customs clearance in Country Y.

This actually makes no economic sense. Most EU countries have excellent port facilities, and there is no logistical reason for Chinese shippers to use a port in the UK rather than, for example, one in Germany. In fact, the investigations carried out by Member States revealed that even when the first port of entry is in another EU country, the goods are sent by road to Country Y solely for the purpose of Customs clearance, and then travel on to other Member States.

Country Y appears to be attracting far more of this fraudulent traffic than any other EU Member State, and increasingly so over time. In the last four years, the share of undervalued imports through Country Y, when compared to legitimate trade, steadily rose from 32% in 2013 to 40% in 2014, and from 44% in 2015 to 50% in 2016.

To understand the full extent of the phenomenon, OLAF carried out an extensive analysis of all Customs declarations for all imports of textiles and shoes from China between 2013 and 2016. A “cleaned average price” was calculated for each category of textiles and shoes imported from China, based on the value of all import declarations in the EU between 2013 and 2016.

A conservative 50% of that value was taken as the lowest acceptable price for import declarations into the EU, and all declarations below the lowest acceptable price were considered as undervalued, knowing that legitimate trade in that context would hardly be economically viable.

For example, OLAF found that women’s trousers imported from China were declared at Customs in Country Y at an average price of 91 euro cents per kg, although in the same period the world market price for the raw material alone was 1.44 euro per kg, and that the average value declared in the EU for the same products was 26.09 euro per kg. As a result, OLAF calculated a loss to the EU budget of almost 1,987 billion euro in Customs duties.

The investigation also revealed substantial evasion of value-added tax (VAT), cumulatively estimated at approximately 3.2 billion euro for the 2013 to 2016 period, in connection with imports through Country Y by abusing EU Customs procedure 42 (the regime an importer uses in order to obtain a VAT exemption when imported goods will be transported to another Member State). As the goods were largely destined for the markets of other Member States, the revenues of States such as France, Germany, Italy and Spain were mainly affected.

Moreover, OLAF’s investigation uncovered a direct correlation between diminishing traffic in the fraud hubs in other Member States where authorities took action, and an increase in fraudulent traffic through the hub in Country Y. In practice, this means fraudsters have, over time, been shifting their operations to Country Y, in order to benefit from a more lenient regime, or from lack of controls at the point of Customs clearance.

This happened despite OLAF having repeatedly drawn the attention of Country Y’s Customs authorities over a number of years to the scale of the phenomenon and to the ongoing revenue losses. OLAF also alerted Country Y’s authorities to the need to implement EU-wide risk profiles and to investigate the fraud networks active in Country Y.

A “Single Market” requires quality controls

The well-functioning of the EU Single Market is based on controls taking place at its external border, and once cleared, products are generally no longer subject to subsequent checks. Therefore, the poor quality of controls at the point of entry into the EU through Country Y has a direct impact on the revenues of other Member States. Moreover, undervaluation causes significant damage to Europe’s legitimate industry, as European producers simply cannot compete. This, naturally, results in job losses for EU citizens.

Customs control and enforcement are a responsibility of the Member States, and many of them take that responsibility extremely seriously. This means that the EU Customs Union has 28 guardians, and with trade facilitation procedures such as a transit regime in place, any loophole, any weakness and any gap in our Customs system will be exploited by well-organized criminal networks in order to generate illicit profits.

This can happen in cases of undervaluation fraud too, and OLAF has uncovered even more standard cases of transit fraud, such as the remote hacking of national transit systems, the bribing of Customs officers, or instances where sealed shipments were unlawfully discharged before they exited the EU. Currently, transit procedures can be used by any importer, indiscriminately, without any prior checks and with no conditionality.

While many Customs administrations work in an organized, fairly interconnected manner, the results of our investigation are clear proof that Customs officers should increasingly shift their work to risk assessment and to identifying potential problems from the outset.

Less fraud through more integration

Knowing that any slip of a national Customs authority, or any perceived leniency or neglect will lead to huge losses for European citizens, EU Member States should seriously start considering a move towards a single EU Customs Agency.

Working at OLAF, we often investigate across borders and, therefore, see matters outside of the confines of national Member States of the EU. Many times, our work has taught us that national cooperation is simply not enough: to rise to the challenge of fighting highly organized, highly committed and extremely resourceful criminal networks, what is needed is more integration.

While free trade provides us with immense opportunities for growth and development, this cannot take place without a strong enforcement dimension, which ensures international trade is fair, clean and secure, and that Customs checks are uniformly conducted at all points of the EU external border. The European Customs Union should have no weak links, no loopholes, and no “less than.”

OLAF is the only EU body mandated to detect, investigate and stop fraud involving EU funds. While it has an individual independent status in its investigative function, it is also part of the European Commission, under the responsibility of Günther H. Oettinger, the Commissioner in charge of Budget and Human Resources.

In my view, with a single EU Customs Agency, European citizens, as well as criminal networks, will know what to expect – uniform checks, risk assessment, and harmonized enforcement. And ultimately, less fraud!

More information

https://ec.europa.eu/anti-fraud

Acting spokesperson: Silvana Enculescu

silvana-andreea.enculescu@ec.europa.eu