Fragile borders and Customs activities in a post-conflict situation: the case of the Central African Republic

14 October 2017

By Thomas Cantens, WCO Research Unit and Sidoine YEREMI, National Customs Expert, Central African Republic

The Central African Republic (CAR) gained independence in 1960, but has a chequered history of coups d’état and ongoing guerrilla attacks. In 2013, Séléka – a Muslim-dominated coalition of rebel groups from the north, which ousted the former President François Bozizé – became embroiled in conflict with the “anti-balaka,” a resistance network of Christian self-defence militia.

Hostilities between the two groups declined after a de facto partition was established between the Christian south and the Muslim north, but were superseded by an outbreak of fratricidal conflict between the various Séléka factions, which culminated in the official dissolution of the coalition in 2014.

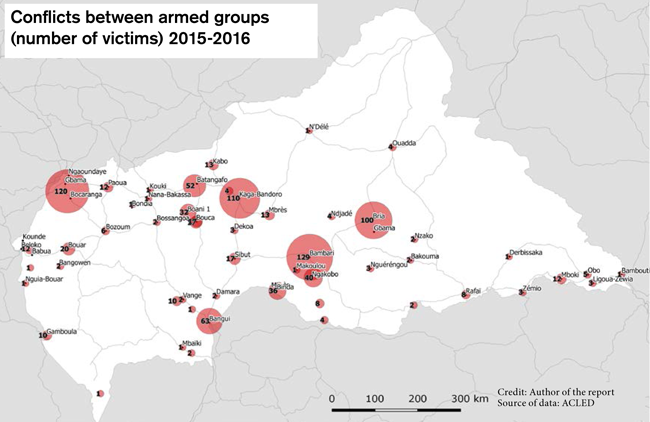

At his investiture on 30 March 2016, the new President announced his intention to focus on disarming ex-combatants, restoring security, and bringing about reconciliation. Armed groups, nevertheless, remain present across large swathes of the country, occupying the north, north-east and east, causing many violent clashes and constituting an obstacle to the redeployment of the State’s administration throughout the country.

A divided territory

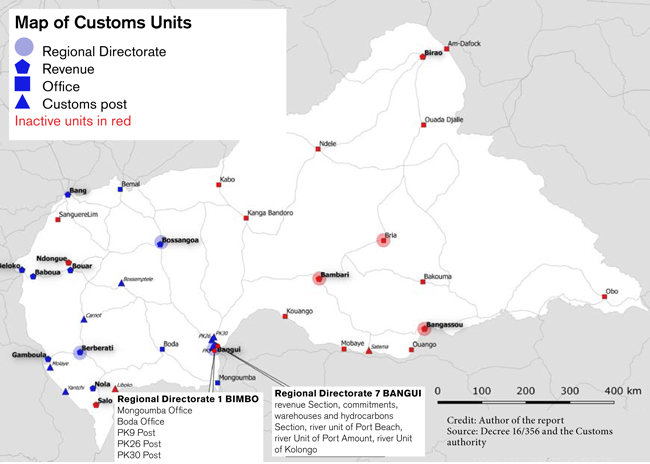

The CAR can be regarded as comprising three separate areas for Customs administration purposes, each with its own specific features and constraints:

- the Béloko-Bangui corridor, which is characterized by the presence of state services and is the focal point for most of the Customs authority’s modernization and surveillance efforts;

- the centre and the east, which are notable for their absence of Customs authorities in any form, and which are dominated by armed political groups that formed in the aftermath of the Séléka rebellion;

- the west (outside the Béloko-Bangui corridor), which is administered by the State, but is facing major security-related challenges – the Customs authority maintains a presence at certain border points and in a number of towns in this area, but the police, gendarmerie and army are largely absent, with security being, for the most part, in the hands of the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA).

This division of the country on the basis of security constraints poses a major organizational challenge for the CAR Customs authority, forcing it to operate in radically different contexts and to facilitate trade along a major economic corridor not only in the “traditional” sense, but also in a “political” sense by contributing to the restoration of the State and economic resilience in fragile border regions.

The Douala-Béloko-Bangui corridor

Maps of the region reveal the high density of transit routes crossing the border between Cameroon and the Central African Republic and the many villages, in particular to the north of the Béloko transit point.

This transit point is where goods travelling from the Cameroonian port of Douala to Bangui, the CAR’s official capital, cross the border. The taxes levied on these goods account for the vast majority of the revenues currently collected by the CAR Customs authority, and safeguarding this stream of funding is, therefore, a crucial challenge for the State.

The Customs officers working at the Béloko post have carried out clearance procedures manually ever since their offices were destroyed in 2012. Concerns over security and the high risk of looting mean that lorries have to travel in convoys of around 100 from Béloko to Bangui and vice versa, accompanied by representatives of MINUSCA and the Economic Customs Brigade. The journey takes around two to three days and covers a distance of 740 km on tarred roads.

Customs administrative activities along the Douala-Béloko-Bangui corridor consist primarily of restoring the flow of revenues from Béloko, with a focus on the Customs clearance procedure for goods from Douala. The project currently under way involves:

- renovation of the Customs buildings in Béloko, some of which will be used as accommodation for Customs officers;

- installation of ASYCUDA software in the office responsible for Béloko revenues in order to automate checking, registration, settlement and payment procedures in relation to duties and taxes on declared goods;

- establishment of a Customs facility in Béloko, in particular an in-bond area for 500 lorries;

- introduction of an option for operators identified as “reliable” to complete the Customs clearance procedure in Bangui rather than Béloko;

- once the Béloko post is operational, dismantling of the CAR Single Window in Douala and the fixed checkpoints along the route within the borders of Cameroon and along the Béloko-Bangui corridor;

- maintenance of a satellite Customs office and an in-bond area for goods in transit to the CAR at the port of Douala.

The CAR Customs authority plans to use its own funds to purchase equipment for the office in Béloko, including computer hardware, network cabling, solar energy devices and satellite communications equipment (VSAT). Most of the funding for the renovation of the office will be supplied by the World Bank under the aegis of its FASTRAC (Facility for Advisory Support for Transition Capacities) Project launched in 2008.

In addition, the Customs authority plans to introduce a performance measurement system to back up these modernization measures. In late 2016, CAR Customs officers visited Douala in order to learn more about Cameroon’s experience of “performance contracts,” with a view to replicating this approach at home. Technical support for this project may be provided by the Cameroon Customs administration, the World Bank and the WCO.

It will be important to ensure that the installation of computer systems at the border post is leveraged as an opportunity to carry out procedural reforms, with due consideration being given to the expectations of private stakeholders (hauliers, freight forwarders, banks and importers). The choice of “reliable” operators is also fraught with difficulties: this process requires solid statistical data on past operations, in the absence of which the State’s decisions will lack impartiality, and be liable to legal challenges, irrespective of the objective criteria upon which they are based. It may prove useful to establish an expert platform where the Customs authorities and local businesses can exchange ideas and discuss related practical issues.

Security constraints represent a further key factor, but are still a relatively unknown quantity for both the Customs authority and the funding bodies. Unofficial hauliers/importers will be keen to bypass a modern Customs office which carries out stricter checks and applies the tax rules more rigorously, but the Customs authority must not forget the risks associated with any coercive measures in a border environment which is both remote and sparsely populated, and thus a fertile breeding ground for protests against state representatives, in particular officials working for the tax and Customs administrations.

The modernization plan for Béloko must, therefore, incorporate measures to ensure the safety of staff and infrastructure, in particular the following: (i) security features to protect the office (boundary walls, cameras, barriers and building security); (ii) arms for Customs officers working in Béloko (including training, drills and an armoury); and (iii) an emergency plan coordinated between the CAR Customs authorities and the country’s army, aimed at protecting Customs officers in the event of riots or attacks on the office.

As far as performance contracts are concerned, there is a risk of underestimating the shift in attitudes that will be required for the initiative to succeed and the workload to be shouldered by the project team responsible for the software. Any miscalculation of an official’s performance would have serious personal consequences for the individual concerned, and undermine the credibility of the system. Time must, therefore, be allowed for the Customs officers to acclimatize to a new working culture and for the programmers to test the performance measurement software.

The centre and east of the country

This area is under the control of armed political groups linked by a variety of alliances. Some of the more politically motivated of these groups are in favour of partitioning the country along religious lines, officially enshrining the de facto situation which exists today, with the self-proclaimed “Republic of Logone” having its capital in Birao. Other groups are more likely to condone the laying down of arms and participation in a programme of disarmament, demobilization and reintegration (DDR) or a community violence reduction programme aimed at rehabilitating ex-combatants. Finally, certain groups do not pursue any particular political objectives, making a living from the violent extortion of levies on flows of goods and people.

MINUSCA forces are chiefly responsible for providing security in a small number of towns, together with the few members of the police and gendarmes present in the same towns. No other state services are present: delegations were recently sent by the administration (in particular Customs) to local commanders, but the latter refused to countenance the presence of fiscal authorities.

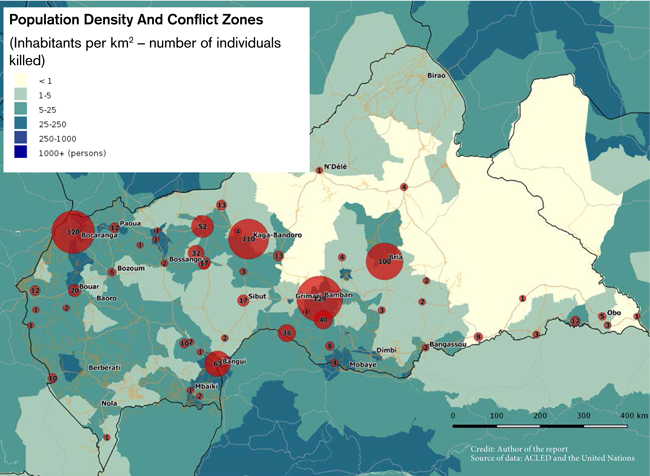

The area presents major challenges, particularly in terms of tax revenues: for example, goods from Sudan, which had probably transited through the area were observed during a visit to Market PK5 in Bangui. The shortfalls are difficult to estimate, but the taxes levied on legitimate commercial transactions in this area fund armed groups in just the same way as the illegal trade in gold and diamonds.

The very existence of this large area furthermore poses a threat to the economic fabric of Bangui and the area under governmental control, since the tax burden imposed by the armed groups on traders who import products via neighbouring countries is potentially less than that imposed by the State on traders who import their goods via the Douala-Béloko-Bangui corridor, making the former more competitive than the latter. This gap between these two groups is likely only to widen when the CAR Customs authority “secures” its revenues from the Douala-Béloko-Bangui corridor.

Data analysis is an essential prerequisite for political debate in this context, and the Customs authority will have a vital role to play in this regard. Useful information can be obtained by means of the following measures:

- an estimation of the flow of goods between the Séléka area (areas controlled by armed groups which belonged to Séléka and who continue to exert a presence on the ground) and the government-controlled area by way of, for example, anonymous surveys at Market PK5, fact-finding missions at border points in cooperation with the Customs administrations of neighbouring countries, and on the basis of data supplied by local telecommunications operators);

- an estimation of the tax revenues collected by armed groups at the Government’s expense,

- an analysis of trade flows in order to optimize the deployment of surveillance units, with the aim of protecting the official economy in the area under state control.

The west of the country outside the Béloko-Bangui corridor

The main transportation routes in this area are controlled by “auxiliaries” (generally armed groups such as the “anti-balaka” and “self-defence groups”) rather than the security forces.

Cross-border trade in the area provides funding for armed groups, which levy charges known as “formalities” on every vehicle. Although the Customs authority collects duties and taxes on certain routes, the level of insecurity in the area prevents any real deployment. The risk here is that local governments will be established in opposition to the central State: the political representatives of the State, lacking the financial backing to demonstrate the clout of the State, would rely on “economic elites” who would provide them with their means of livelihood, and on armed self-defence groups who offer security to all who supply financial or in-kind support.

The CAR Customs authority has collected data on revenues and passages of vehicles and goods, and also holds information on the trading environment gathered in the course of interactions with hauliers and traders. The main challenge in this area is to structure the information which currently exists in the form of disparate knowledge held intuitively by Customs officers, and to plan the deployment of units on the ground on the basis of trade flows and security considerations.

Support from security partners (MINUSCA and the national security and defence forces) is vital, particularly in this area. It is also important to understand the position of local economic elites in order to forestall any involvement with local armed groups.

Conclusion

The CAR Customs authority requires support from the international community in respect of three key challenges.

The first is the adoption of a global strategy for the territory of the CAR, or in other words a strategy which covers the problems examined above on an area-by-area basis. The lack of human and financial resources means that it is very tempting to focus on the Béloko-Bangui corridor, but in the short term, the economy of Bangui itself risks destabilization as a result of the shadow economy throughout the country.

The second is corruption, which angers local populations and discourages cooperation with state services, and in the long term promotes the establishment of local armed groups, which supply “security” services directly to residents. Customs officers must, therefore, on the one hand, be encouraged to prioritize data analysis activities, which are particularly important at a time when some of the country’s borders are fragile and the Government needs not only Customs revenues, but also data on the economic impacts of insecurity.

On the other hand, Customs officers must be discouraged from favouring posts in the “safe” area, and the working conditions of those working in “unsafe” areas must be improved to ensure that their personal safety does not depend on the good will of local militia. Senior Customs management is fully aware of this risk, and has taken steps to prevent it by stepping up internal inspections and awarding bonuses to a larger number of employees. Performance contracts will also play a key role in the fight against corruption.

Finally, the CAR Customs authority requires data as a basis for decisions. One of the features shared by all fragile borders is that the State is relatively unaware of the local situation: since Customs officers on the ground are familiar with the environment in which they work, it is vitally important to gather and structure the knowledge they hold with a view to analysing local situations and facilitating decision-making processes.

Priority should, therefore, be given to the introduction of appropriate statistical procedures by the Customs authority and the gathering and structuring of information and intelligence gained from revenues, both in order to plan reforms and monitor their implementation on the ground, and to provide the CAR Government and society with a better insight into the “economy of violence” in the border areas.

More information