Controlling dual-use goods in a transit country: Lithuania’s experience

22 October 2019

By Rolandas Jurgaitis, Deputy Head of Customs Procedures, Customs Department, Ministry of Finance and Enrika Naujoke, Director of the Customs Practitioners Association, LithuaniaExport controls are inherently challenging to implement, and no country has a perfect or fool-proof system. In this article, the Customs Department of Lithuania shares information about the specific challenges that the country is facing with dual-use goods, and the latest actions that have been taken to mitigate risks and improve compliance by trade operators.

Background

Since the early 1990s, a number of countries have participated in multilateral export control arrangements to produce guidelines for the control of strategic goods. These types of goods encompass weapons of mass destruction (WMD), conventional weapons, and related items involved in the development, production or use of such weapons and their delivery systems. Under these related items are goods with both civil and military applications called dual-use goods.

Under the various export control arrangements, lists have been compiled of dual-use materials, components, equipment, and technology that are subject to export controls. The European Union (EU) has consolidated these lists into one integrated dual-use list, the common EU list of controlled items, creating the most internationally adopted control list for these types of strategic commodities.

The EU regulation (No. 428/2009) requires dual-use items to be subject to effective control when they are exported from or transit through the Union, or are delivered to a third country as a result of brokering services provided by a broker resident or established in the Union.

Each entry on the list consists of a five-character Export Control Classification (ECN). The first character corresponds to the topical category for the item, the second corresponds to the type of item (for example, D = software), while the third character identifies the multilateral regime under which the item is controlled (for example, 0 = Wassenaar Arrangement). The remaining characters correspond to the description of the controlled item.

Sorting out which commodity is subject to export control requirements can be a cumbersome process for companies. To assist them, a correlation table between the ECN and TARIC, the EU’s integrated tariff, has been developed. However, the relevance of correlations is so uneven, and not all correlations are equally indicative.

When the Customs tariff code indicates a correlation with the common EU list of controlled items, exporters must indicate whether the goods they are exporting are subject to export control or not by inserting special codes when filling in the Single Administrative Document (i.e. the EU Customs declaration): code X002 if goods are controlled, or code Y901 if goods are not controlled.

Moreover, the EU regulation also includes a “catch-all” clause for non-listed items, which could be used, for example, in a WMD programme (Article 4 of the EU regulation). An exporter must, therefore, notify the authorities if he is aware that dual-use items which he proposes to export, not listed in the list of controlled items, are intended, in their entirety or in part, for military end-use. The authority will then decide whether the export concerned should be subject to authorization.

Determining whether traders are compliant is a challenging task for Customs. Knowledge of both the Harmonized System (HS) and the ECN, as well as a solid analytical methodology, is necessary. In Lithuania, the situation is even more problematic due to the type of logistics operations carried out in the country.

A transit country

A Member State of the EU located along the Baltic Sea, between East and West, Lithuania is facing specific challenges when it comes to the implementation of EU export control regulations, especially since the bloc implemented restrictive measures against Russia in 2014, which impose an export and import ban on trade in arms, establish an export ban for dual-use goods for military use or military end-users, and curtail access to certain sensitive technologies and services that can be used for oil production and exploration.

Lithuania’s geographical location favoured the development of a strong logistics sector and the establishment of a broad network of 189 freight terminals and Customs warehouses, dealing mainly with goods in transit.

In 2018, compared to 358,076 imports and 366,298 exports, more than 1 million transit operations were processed by the Customs Department. These operations include goods placed under the EU common transit procedure, covered by the TIR Carnet, transhipped within, or directly re-exported from, a free zone, in temporary storage, and directly re-exported from a temporary storage facility.

Let’s highlight here that, regarding dual-use goods, it has been agreed within the European Community (EC) that the term “transit” shall be understood to mean the “transport of non-Community dual-use goods, which are introduced into the Customs territory of the Community for transport through that area to a destination outside the Community.”

The risk of non-compliance with dual-use goods regulations is high for several reasons:

- When “Union goods” arrive at a freight terminal or in a warehouse for export, the terminal operator or the logistics company takes the role of a consignor/exporter in the export declaration, but often does not have sufficient information about the technical specifications of the goods and the circumstances of the sale and its parties to assess whether the exported commodity requires a permit or not. Moreover, a large number of players in the logistics market are new and have little or no knowledge of international controls relating to dual-use goods.

- When “non-Union goods” arrive at a terminal or a warehouse for export, the consignment is placed under a Customs regime. For instance, temporary storage, transit, Customs warehousing, or re-export. Enforcing export control regulations is even more complex in such a case, as the compliance requirements must be understood and met by all the participants in an operation (forwarders, transportation companies, storage companies, Customs brokers, etc.). They must each hand over correct information and documents to the next party in the chain. In doing so lies the risk of mistakes occurring, especially when a re-sale of goods has taken place.

- Non-Community dual-use goods that transit though the EC only, and as such through Lithuania, are usually not subject to a licence requirement. If some EU Member States require an authorization for all external transits of dual-use items, this is not the case in Lithuania where authorities may, instead, prohibit the transit of non-Union dual-use items where they have reasonable grounds for suspecting from intelligence or other sources that the items are or may be intended, in their entirety or in part, for the proliferation of WMD or of their means of delivery, or for military end-use in a country subject to an arms embargo.

- The declarant does not have to select codes X002 or Y901 if the goods are in transit according to the EC definition given above. In fact, the transit procedure and the TIR Carnet do not even include this information.

Operation COSMO

Lithuanian Customs’ enhanced focus on the issue has its roots in its participation in law enforcement operations organized by the WCO: COSMO (2014), and COSMO 2 (2018). The objectives of these operations were to detect and prevent illicit trafficking of strategic goods in international supply chains, and to assess the capacity of Customs administrations to enforce strategic goods regulations. To achieve this latter goal, all participants were asked to complete a national self-assessment of their national standard operating procedures and work practices in this area.

Based on these national self-assessments, it has become clear that the issue of strategic trade control enforcement was a new and challenging area for many WCO Members. Fortunately, the timing of the first COSMO operation coincided with the adoption by the EU of restrictive measures against Russia and enabled Lithuanian Customs to fully assess its capacity to enforce the measures.

Various areas requiring capacity enhancements were identified. These related to issues such as the lack of skills and insufficient technical/scientific knowledge of frontline officers to identify and detect dual-use goods. Although Lithuanian Customs does reach out to others, including local industries, that may have more knowledge, cooperation from foreign law enforcement entities and scientific institutions has not been very forthcoming.

To maintain the momentum and identify ways of improving the situation on the ground, Lithuanian Customs recently launched its own enforcement operation, code-named SPEK 2019, at the beginning of this year.

SPEK 2019

A three-stage approach was adopted for the operation, each focusing for a specific duration on one of the three commodities identified as problematic: anamide, glass and carbon fibre (duration 1 week); aluminium alloys (duration 1 week); and ultrafiltration membranes (duration 3 months).

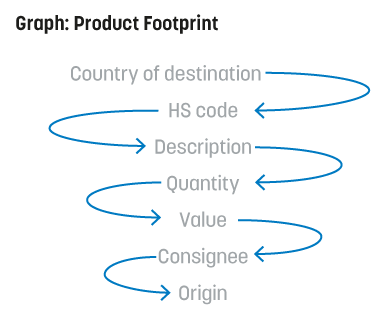

A risk profile was built for each of the commodities, and Customs officials received training on how to handle the clearance process when the pre-determined risk profiles were identified by the risk engine. The “Product Footprint” method was applied, and the sequence of actions is shown in the illustrative graph.

The results of Operation SPEK 2019 are as follows:

- In five cases, the clearance procedure was stopped as the goods were listed as dual-use, but not declared as such, and an export authorization was requested for the procedure to take its course;

- Out of the 10 freight terminals that were randomly selected and audited, two were found not to be in compliance during two separate operations – a dispute is ongoing with one of them, while the other paid the pecuniary (money) penalty stemming from the infringement;

- The export of a non-listed item originating from an EU country was rejected.

The export that was rejected had to do with fibreglass mats, which were produced in another EU Member State and loaded for export in Lithuania. Fibreglass mats are not listed as dual-use goods in the EU regulation, but they can be used in certain military technologies and considered as falling under the catch-all clause for non-listed items.

In such cases, Customs takes into consideration the intended use of the product, the risk associated with the consignee, or the “sensitivity” of the destination country/region. In this specific case, as the consignee of the fibreglass mats was a company involved in the production of military equipment, Customs rejected the export and asked the consignor to present an export authorization.

Regarding SPEK 2019, the following observations were made:

- A significant number of logistics companies have insufficient understanding of their non-proliferation obligations, do not have personnel responsible for compliance, and, as such, do not assess the risks in the manner required.

- Some companies are knowingly involved in the export of dual-use goods, using Lithuania as a transit country in the hope that the authorities will not ask for an authorization.

- Citizens of some sanctioned countries set up front companies in Lithuania, to hide the link with their country and contract logistics companies to act as the consignor/exporter in export declarations.

Enhancing compliance and cooperation

A key challenge to the enforcement of export controls in Lithuania and in many countries relates to outreach and raising awareness. Aware that the private sector needs assistance in identifying, managing and mitigating risks associated with dual-use trade controls and in ensuring compliance with relevant EU and national regulations, the European Commission (EC) released, in July 2019, a Recommendation on internal compliance programmes (ICP) for dual-use trade controls, under a Council Regulation. The EC guidance focuses on the seven core elements for effective ICP:

- Top-level management commitment to compliance.

- Sufficient organizational, human and technical resources with well-defined responsibilities.

- Staff is regularly trained and informed on the issue.

- A process is established to evaluate whether or not a transaction involving dual-use items is subject to trade controls, and to determine the applicable processes and procedures.

- ICP must be reviewed, tested and revised if proven necessary, and clear reporting procedures in place about the notification and escalation actions of employees when a suspected or known incident of non-compliance has occurred.

- Proportionate, accurate and traceable recordkeeping of dual-use trade control related activities is essential, including for documents not required by law (e.g., an internal document describing the technical decision to classify an item).

- Internal procedures must ensure the prevention of unauthorized access to or removal of dual-use items by employees, contractors, suppliers or visitors.

Each core element is further detailed by a section ‘What is expected’ that describes the objective(s) of each core element, and a section ‘What are the steps involved?’ that further specifies the actions and outlines possible solutions for developing or implementing compliance procedures. This document concludes with a set of helpful questions pertaining to a company’s ICP, and a list of diversion risk indicators and “red flag” signs about suspicious enquiries or orders.

Lithuanian Customs provides advice to all parties that deal with export control regulations, in order to facilitate compliance with the EC Recommendation. Customs officials also regularly organize events on the subject or participate in events organized by associations or private sector training providers. In addition, they contribute to the monthly journal “Customs Law for Practitioners” issued by the private sector, to share their knowledge and shed light on specific regulations.

Feedback from participants in training events has been very positive. The main challenge, however, lies in educating employees and companies who show no interest in the issue and who do not want to attend seminars or follow online training courses. Unfortunately, for these types of actors, audits and penalties may be the result of their reluctant attitude.

More information

rolandas.jurgaitis@lrmuitine.lt