Customs Brokers: An overview of the outcomes of the WCO Study Report

26 June 2016

In order to provide a clear understanding of practices relating to the role of brokers, including institutional frameworks and the regulatory/licensing requirements, and to further provide guidance to its Members, the WCO developed a Study Report on Customs Brokers. Besides reviewing Members’ practices, the Study, which is based on the results of a survey and research carried out by the WCO Secretariat, provides some policy and organizational considerations to serve as a reference point for Customs administrations who are considering the establishment or adjustment of a licensing/regulatory regime for brokers.

Back in 2015, a questionnaire was circulated to all WCO Members in order to ascertain Customs administrations’ practices concerning Customs brokers. Ninety-nine countries (55% of the WCO membership) responded to the survey questionnaire, which touched on a number of themes such as licensing requirements, sanctions/penalties, obligations, restrictions, and cooperation mechanisms.

Ninety-five reporting administrations stated that their country has some or other mechanism for Customs brokers, agents, representatives or third parties who act on behalf of traders to handle Customs clearances and related activities. The remaining four countries did not have any requirements for such activities – as a result thereof, they did not provide any framework for the profession.

The first finding of the Study is that there is a wide range of models among countries regarding the use of Customs brokers. The function of a Customs broker also varies greatly, from the preparation of documents related to release and clearance, to the payment of duties and taxes, to providing assistance in post clearance audits, to representing clients in dispute resolutions, and to providing advice/consultancy services to traders aimed at helping them to meet various regulatory requirements.

As there is “no one size fits all” solution, the Study suggests a basket of considerations that could serve as a reference point for countries wishing to establish or adjust a regime for brokers. This article examines some of these considerations, while highlighting some of the WCO survey’s findings under each consideration.

Optional/mandatory

Consideration: Use of Customs brokers should be made “optional” in line with the provisions of the WCO Revised Kyoto Convention (RKC), and could potentially be governed by free market principles as are other professional services, keeping in mind the national social and economic situation.

The RKC obligates countries to make the use of Customs brokers’ services “optional.” The World Trade Organization’s (WTO’s) Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA) provides that, from the entry into force of the Agreement, Members shall not introduce the mandatory use of Customs brokers. However, mandatory use of licensed brokers’ services is still prevalent in many parts of the world, for example in the Americas and Caribbean region or in some African countries.

Chapter 8 of the RKC

Standard 8.1: Persons concerned shall have the choice of transacting business with the Customs either directly or by designating a third party to act on their behalf.

Article 10.6 of the WTO TFA

Paragraph 6.1: Without prejudice to the important policy concerns of some Members that currently maintain a special role for customs brokers, from the entry into force of this Agreement Members shall not introduce the mandatory use of customs brokers.

Of the 99 reporting administrations, 72 stated that the use of Customs brokers was optional. Nine reported that the use of Customs brokers for Customs transactions was mandatory. Fourteen indicated that the use of Customs brokers was mandatory, except for certain specified categories of Customs clearance transactions, threshold values and goods – household goods, used cars, non-commercial samples and postal items were given as examples.

Fees and charges

Consideration: Fees and charges for Customs brokers should be neither fixed nor regulated by an authority, and should be left to be determined by the market. However, depending on national-specific requirements, general oversight may be required to protect the interest of traders.

Following free market principles means that the engagement of the services of a Customs broker or a similar entity is a commercial decision by traders. Eighty-one reporting administrations noted that free market principles apply in their respective countries. Only in the case of 12, are fees either fixed or monitored in some way (e.g. setting out minimum fees or flat rates) by a government authority, mainly a Customs administration, and in some instances by Customs in concert with a private sector body. Such practices may have been adopted to avoid brokers overcharging for their services or to avoid cartels or monopolistic situations.

Individuals and companies

Consideration: Both individuals (natural persons) and companies (legal persons) should be permitted to become licensed brokers, in cases where licensing is required. This is to ensure equal opportunities for everyone, and also to have a wider availability of brokers.

This is, according to the survey, the case in 45 countries. In 24, only companies or legal persons can become licensed Customs brokers. At the same time, in 15 countries, licensed Customs brokers are solely individuals or natural persons. Apparently, more WCO Members have corporate entities as licensed Customs brokers than individuals, although in many cases these companies need to assign at least one Customs broker/Customs specialist. Retired/former Customs officers are also allowed to act as brokers by some countries subject to specific conditions – for example in Korea, 54% of brokers are currently former Customs officers.

Customs as the regulatory and licensing authority

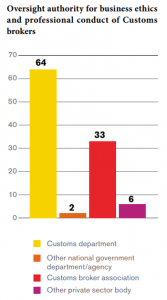

Consideration: Due to the nature of the activities carried out by Customs brokers, which are primarily related to Customs clearance, Customs should, to the extent possible, be the regulatory and licensing authority for Customs brokers, where applicable. Responsibility for conducting examinations for brokers, where applicable, may also be entrusted to Customs. Where needed, Customs could – together with brokers’ associations or any other private body – also be entrusted with oversight authority in respect of the business ethics and professional conduct of Customs brokers.

In 80 countries, Customs has the responsibility of such an authority. Eight reporting administrations indicated that this authority is vested with another government department or agency, such as the Ministry of the Economy in Moldova, and the Professional Regulation Commission in the Philippines. At the economic community/Customs union level, such authority often lays with the respective community/union (e.g. Economic Community of Central African States, or ECOWAS). In the case of two countries, a private sector body such as a trade association or a Customs agents chamber is the regulatory and licensing authority (e.g. British International Freight Association, or BIFA, in the United kingdom).

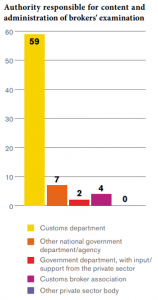

Fifty-nine reporting administrations that do have an examination as part of the licensing process have delegated the responsibility of the examination’s content and administration to their Customs authority. Seven countries have other national government departments/agencies responsible for this, for instance the Ministry of Finance’s Training Institute in the Dominican Republic, the Human Resource Development Service in Korea, the International Business and Customs Institute of Riga Technical University in Latvia, a Tribunal (comprising one representative each from the Ministry of Economy and Finance, the Customs Directorate and the Brokers’ Association) in Uruguay, and the Customs Broker’s Board in Trinidad and Tobago.

Two reporting administrations stated that in their country, a government department is the responsible body, but with the input and support of the private sector (e.g. Professional Regulation Commission with inputs from the Chamber of Customs Brokers in the Philippines). Four reporting administrations have given this responsibility to a Customs brokers association, apparently to optimize government’s limited sources.

Licensing requirements and penalties for brokers

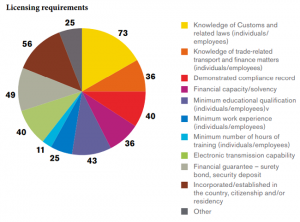

Consideration: Regulatory and licensing criteria, where applicable, should be transparent, non-discriminatory and simple, and may specifically include sanctions and penalties for misconduct and violations, including provisions dealing with informal/unauthorized brokers, in order to ensure effective compliance with Customs and other government agencies’ requirements.

The RKC and the WTO TFA requires that national legislation and rules setting out licensing requirements for Customs brokers should be transparent, non-discriminatory, and reasonable.

Article 10.6 of the WTO TFA

Paragraph 6.3: With regard to the licensing of customs brokers, Members shall apply rules that are transparent and objective.

Of the 95 reporting administrations which have set out some sort of mechanism for Customs brokers, 84 require Customs brokers, and wherever applicable third parties, to meet certain requirements before being allowed to handle Customs clearances. Detailed results on the requirements as well as their use are presented in the chart below.

Requirements for traders

Consideration: Where licensing requirements, if any, are foreseen for traders who are permitted to carry out Customs formalities for the clearance of their own goods, they need not necessarily be as stringent as the licensing requirements for Customs brokers; however, some minimum prerequisites such as knowledge of Customs and related laws, a good compliance record, and financial solvency could be prescribed.

In countries where traders are allowed to handle their own Customs clearance formalities, they are in general subject to requirements broadly similar to those of Customs brokers. In 19 of the reporting countries, traders can handle their own Customs formalities with no requirements from the government or Customs. In some cases, though, such a facility is restricted to manufacturers and government agencies only.

Examination

Consideration: In order to test the Customs knowledge of brokers and ensure that they keep themselves abreast of the latest developments, Customs administrations should consider designing suitable assessment/verification systems, for example, an examination which could be either written or oral.

Sixty-five reporting administrations stated that they have an examination system for verifying/testing Customs brokers’ knowledge of Customs and related laws/regulations, prior to licensing a Customs broker. Twenty countries did not have an examination requirement. Ten countries, including some who do not have an examination system, employ additional means for verifying the Customs knowledge of brokers.

A sample of the methods used to verify brokers’ Customs knowledge include: the conducting of interviews (Australia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo); the completion of an approved course of study (Australia); a Customs diploma programme (Fiji); a specific training programme (Malta); five years of work experience in Customs matters (Mexico); and a “fit and proper person assessment” based on education, work experience, and industry knowledge (Seychelles).

Obligations and liabilities

Consideration: Obligations and liabilities of brokers may include representing their clients under proper authorization, advising their clients on various compliance requirements, carrying out due diligence on their clients and the information submitted to Customs, and not lending their licence or permitting any other person or agent to use it under any circumstances. They may also be jointly and severally liable for the payment of duties, taxes and other charges on behalf of their clients.

Chapter 8 of the General Annex to the RKC

Standard 8.2: National legislation shall set out the conditions under which a person may act for and on behalf of another person in dealing with the Customs and shall lay down the liability of third parties to the Customs for duties and taxes and for any irregularities.

Challenges

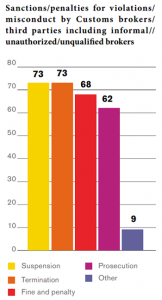

Consideration: Challenges posed by some brokers, including informal/unauthorized brokers, could be met to some extent by increased use of information and communications technology (ICT), the application of demonstrative sanctions and penalties in appropriate cases, and through constant dialogue with traders and with such brokers.

According to countries’ differing regulations, suspension, termination, fines and penalties, and prosecution are all potential sanctions that could be imposed on Customs brokers/third parties for violations or misconduct. Usually, the nature of a sanction would depend on the gravity of the offence. For example, in cases of minor infractions, the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) would simply provide advice and guidance to brokers to rectify their mistakes.

Asked about informal or unauthorized Customs brokers, 29 reporting administrations indicated that it was not a very serious problem, while 13 stated that it was a very serious problem in their country. In terms of measures being taken against such practices, one country is reportedly trying to limit the entry of informal brokers by insisting on the wearing of uniforms and the display of identification (ID) cards, in order to “sanitize” operations at Customs ports, as well as by imposing penalties and sanctions. Another country indicated that their Customs administration was also cross-checking with the tax authority, in order to verify that the person who issues the bill for broker services is authorized to do so.

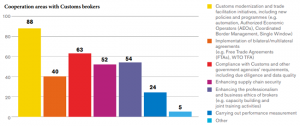

Cooperation

Consideration: Opportunities for cooperation between Customs and brokers could include: Customs modernization and trade facilitation initiatives; implementation of bilateral/multilateral agreements; compliance with Customs and other government agencies’ requirements, including due diligence and data quality; enhancing supply chain security; enhancing the professionalism and business ethics of brokers (e.g. capacity building and joint training activities); and carrying out performance measurement (including conducting Time Release Studies). Where appropriate, Customs brokers could also be involved in the National Committee on Trade Facilitation set up/maintained under the WTO TFA.

Chapter 8 of the General Annex to the RKC

Standard 8.5: The Customs shall provide for third parties to participate in their formal consultations with the trade.

Bilateral consultation, including through a brokers association (in a few cases by way of a Memorandum of Understanding, or MoU – e.g. Bhutan, Moldova, and Uruguay), is the most prevalent mechanism stated by 76 reporting administrations. Sixty-six countries have a broad consultative process involving all trade stakeholders, including Customs brokers. Seventeen have started to consult Customs brokers, as part of their National Committee on Trade Facilitation established under the WTO TFA or any other similar existing body.

AEO/trusted trader programmes

Consideration: The remit of authorized economic operator (AEO)/trusted trader programmes should be expanded to include brokers, with well identified tangible benefits.

Fifty-eight reporting administrations who have implemented an AEO/trusted trader/compliance programme also include Customs brokers in such programmes. The benefits extended to Customs brokers in these programmes vary from one country to another. For instance, in the case of Japan, benefits include the pre-arrival filing of an import declaration, and the facility to pay duties after the release of the cargo. Benefits provided to such brokers in other Customs authorities include a reduced data set for summary declaration, simplified clearance, self-assessment of declarations, access to training courses and pilot projects, service outside of office hours, extended licence validity period, reduced guarantees, and a “coordinator” facility.

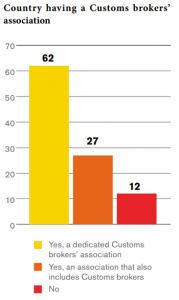

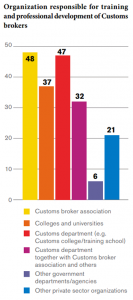

Brokers’ associations

Consideration: Consideration could also be given to establishing/recognizing a brokers’ association at the national/regional level, as such associations can provide support to their members while assisting Customs administrations with the fulfilment of their regulatory/licensing responsibilities. These associations can also provide valuable training, capacity building, and an oversight framework which, given the limited resources some administrations may have, might add to the overall capacity of brokers. However, Customs administrations should support Customs brokers, including through brokers’ associations, by informing/educating them about the regulations and requirements, including, where appropriate, those of other government agencies.

Compliance rate

Consideration: Consideration could also be given to measuring the compliance rates of traders who use a Customs broker against those who do not, alongside studies that measure the release times of traders who use a Customs broker against those of traders who do not. Such studies, conducted at regular intervals, could provide valuable insights into the role and responsibilities of Customs brokers, and identify potential areas for further improvement.

Eighty-two reporting administrations stated that they have not measured the compliance rates of traders who use a Customs broker against those who do not. Seven countries who have conducted such a study did not indicate any clear finding on whether the compliance rate was better with the use of brokers or otherwise.

In a similar vein, 85 reporting administrations noted that they had not measured the release times of those who use a Customs broker against those who do not. Six countries who did carry out such studies had mixed results.

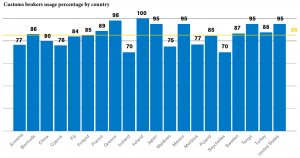

Extent of use

Consideration: Consideration could also be given to ascertaining the extent to which Customs brokers are used in the Customs clearance process. Several Members reported a high percentage of use of brokers despite this being optional in their jurisdiction. Outcomes of such studies might necessitate policy changes not only in terms of adjusting licensing requirements, but also in setting up an effective oversight and capacity building mechanism.

Twenty reporting administrations, where the use of a broker is optional, have ascertained the extent to which Customs brokers are used. In those countries, the average percentage of broker usage was 85.26%, even reaching 99.99% in some cases.

This brings to light the possibility of eliminating any “mandatory” use of brokers to comply with the RKC, rather letting usage be decided by traders/individuals based on market principles – as is the case with most other professional services. This also makes a good business case for those countries that are apprehensive about the social and political issues surrounding the elimination of the mandatory use of brokers.

More information

www.wcoomd.org