Facilitating trade against a backdrop of security threats: the Tunisian experience

20 February 2017

By Mourad Arfaoui, Capacity Building Directorate, WCO and Thomas Cantens, Research Unit, WCOAt the end of June 2016, a group of WCO experts went to Tunisia as part of a research programme on barriers to trade facilitation with a particular focus on potential obstacles linked to the implementation of the World Trade Organization’s (WTO’s) Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA). The WCO-led programme is being carried out in a number of countries, with support from the Korea Customs Administration.

The experts were particularly interested in the way in which Tunisian Customs officials perceive trade facilitation, the measures already in place to facilitate trade, and any barriers to trade facilitation – one of the most significant being security-related issues of increasing concern on the ground.

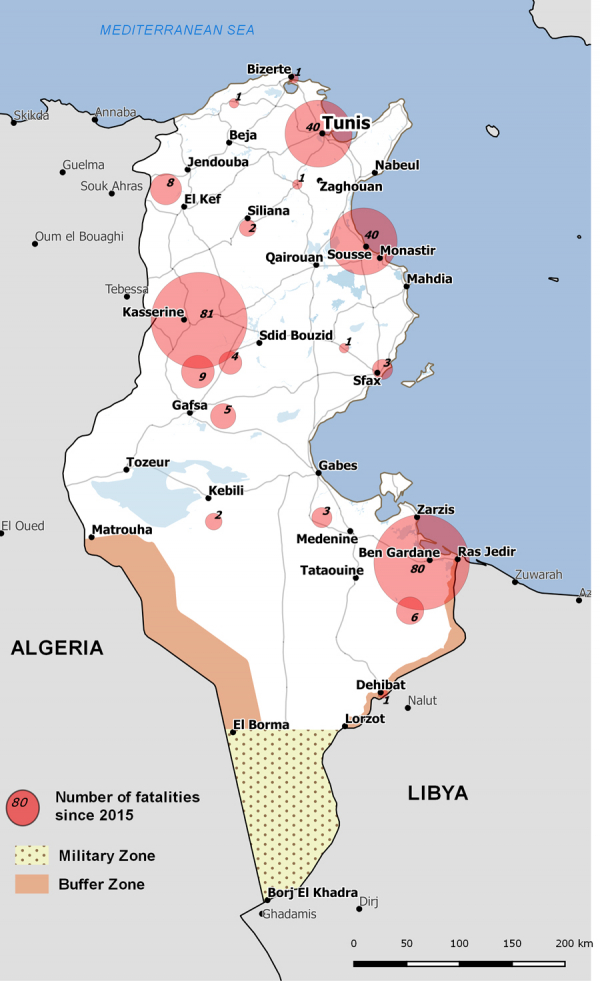

For several years now, Tunisia has witnessed a series of violent attacks perpetrated by armed groups or individuals. The attacks carried out at the Bardo Museum in Tunis (March 2015), in a hotel in Sousse (June 2015), and in Ben Gardane (March 2016) received a considerable amount of media coverage given the scale of the attacks. According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data (ACLED) academic project, over 50 violent armed attacks were recorded in Tunisia in 2016, killing 105 people, two of which were Customs officials.

The security situation remains difficult, particularly in the city of Ben Gardane (a trade hub where both formal and informal trade flows cross the border between Tunisia and Libya), evidenced by the following incidents:

- August 2015 – an armed group claimed responsibility for an attack against a Customs patrol, killing one Customs official;

- 19 November 2015 – a Customs patrol at the border outpost of Sidi Toui (50 km south of Ben Gardane) apprehended three terrorists who were trying to enter Tunisia from Libya illegally;

- March 2016 – an armed group claiming to be part of the Islamic State group (designated a terrorist organization by the United Nations) entered the city of Ben Gardane, killing several people, including a Customs official and a police officer, and tried to create a people’s uprising against the central government, and in particular against Customs officials, whom they accused of threatening informal trade, the biggest source of revenue for the region.

The WCO experts carried out a number of individual and group interviews with Customs officials and operators in the informal trade sector. They also carried out onsite visits at the port of Radès, Tunis-Carthage airport, the Ras Jedir border post on the border with Libya, in goods warehouses in Ben Gardane, and at the outposts of El M’guissem and Sidi Toui on the border with Libya.

This article briefly lays out the initial analysis carried out by the experts and the potential areas of work, which, in their opinion, would enable Tunisian Customs to develop policies to ensure a balance between facilitation and security, taking into account their specific environment, priorities and means, and not necessarily based only on outside recommendations.

Facilitation: a concept firmly rooted in working culture

The majority of senior Customs officials that the WCO experts met with stated that they were highly aware of the facilitation aspect of their job. Trade facilitation as a concept is visibly anchored both in the representations and working culture described by senior officials. Technical and procedural measures have been put it place in order to facilitate the treatment of trade transactions:

- less time-consuming procedures for perishable and flammable goods (release in under six hours);

- an electronic Single Window for submitting documents accompanying a Customs declaration (used in 90% of operations);

- an automatic selectivity programme with centralized risk management in place at Customs‘ headquarters;

- the possibility of making a Customs declaration without using an authorized Customs broker (option used in less than 10% of Customs declarations);

- the possibility for certain operators to submit an advance Customs declaration (request for authorization to remove goods – under 10% of cases)

- an authorized economic operator (AEO) programme (very stringent selection criteria, with 24 authorized operators at the airport)

- the use of non-intrusive inspection equipment;

- deferred inspections for Customs declarations.

The officials that were interviewed recognized the need to take measures to strengthen trade facilitation policy, including:

- simplifying Customs procedures;

- improving the current Customs IT system;

- overhauling the risk management policy by updating the risk indicators;

- improving coordination between the different stakeholders at the border (Customs, police, agricultural authorities, health authorities, certification bodies, etc.);

- improving information sharing between headquarters and local units on the ground in order to ensure that facilitation policy is turned into concrete measures and actions – adopting the WTO TFA should involve running an awareness campaign for staff on the ground who, while they know of the Agreement, do not have a good understanding of all its provisions.

Procedures and security measures at different border posts

While all senior officials interviewed (at the port, the airport, and the border with Libya) did express their willingness to facilitate trade, it is clear that trade facilitation cannot take the same form at all border posts.

Port of Radès

According to senior Customs officials, since 2003 security measures have been stepped up at the port of Radès through which a large majority of Tunisia’s foreign trade transits: the surveillance unit has been bolstered; a canine unit is now up and running; a video surveillance system has been put in place (74 cameras); there is a plan to install new scanners (4 to 6 scanners); and staff are being trained to use the scanners to detect weapons.

Rolling out such additional measures, however, has not involved any overhaul of procedures. The security controls have simply been added to the administrative procedures already in place: the majority of cargo is released “immediately” after being scanned on leaving the port; and the canine team is used systematically to inspect personal effects.

Here, facilitation is understood to mean minimizing delays. As such, security-related obligations, particularly the use of scanners, can lead to differing viewpoints between experts from international organizations, whose main concern is to ensure that a standardized approach to Customs procedures is followed (risk analysis, reduce inspections to a minimum, etc.), and Tunisian Customs officials, for whom there is a lot riding on security, both at a national and personal level.

At a national level, any action by an armed group would have disastrous economic consequences. While at a personal level, any Customs official having dealt with an import in which the means to carry out an attack were concealed would be subject to scrutiny, and serious doubts would be raised about their integrity in an environment where corruption is taken as a given. It is clear then that certain Customs officers do not want to take any risks, both in order to protect society as a whole, but also in order to protect themselves in the case of poor targeting.

Tunis-Carthage airport

At the airport, the main objective of Customs staff is to facilitate trade and no exceptional security measures appear to have been taken, apart from the systematic non-intrusive inspection of parcels sent by post or express courier. Physical inspections at shop exits is a measure that has been in place for years. This can be explained by two factors which are quite common in airport environments: first, a major objective of air freight is the speed with which operations are completed; and second, airports have traditionally been sensitive to security concerns.

Ras Jedir border post

At the south eastern border, the collapse of the Libyan state means that the issue of border security and the fight against smuggling is even more pressing here. In response to such threats, buffer zones under high military surveillance have been set up in the south of the country, a largely desert area, situated between Libya and Algeria. Access to the area is possible through a few crossing points, but only with authorization from the military. The northern border of the buffer zone is in a place called Matrouha to the west, on the Algerian side, and to the east, on the Libyan side, and is situated at the Ras Jedir border post where the WCO experts travelled to.

At the Ras Jedir border post, armoured (anti-tank) gates have been installed to allow the border to be closed in an emergency. Special lighting facilities make the border point operational 24 hours a day: watchtowers outside the crossing point allow movements on the Libyan border to be monitored, to forewarn of any unforeseen activity by armed groups or large movements of refugees. The number of staff has been increased to 260 Customs officers, each equipped with their own personal weapon. In addition, an armed response unit made up of Customs officials and the National Guard is ready to move on orders from the head of office.

Two joint meetings are held every month to ensure coordination between Customs and the security forces, and emergency action plans have been put in place to ensure coordinated efforts in the event of a problem (terrorist act, influx of refugees, etc.). This is done with the aim of guaranteeing border security. Passengers arriving in Tunisia are scanned systematically, the main objective being to detect any weapons.

At the border outpost of El M’guissem, as at other border outposts where government forces that control the areas between border crossings are based, Customs officers play a purely surveillance role, but do so in very challenging conditions (climate, housing, water and power sources, communication by radio only, etc.). Although the number of seizures is relatively low, the intelligence aspect is an important one, particularly as officials have contact with the nomadic communities.

At Ras Jedir, as at other posts on the border with Libya, the notion of trade facilitation takes on a very specific dimension. It is cross-border trade that sustains the region, and facilitating trade singles out the State as a player in the governance of such fragile regions. In addition, as in other areas affected by insecurity, the ability of an organization (be it the State or a militia) to enable trade across the zone is an indicator to the population of its ability to govern.

As such, the Tunisian State, and in particular Customs, plays an important role in negotiating with Libyan authorities. Any Libyan measure (blocking the release of goods, seizures, taxation, etc.) that has a negative effect on Tunisian traders (mostly informal), couriers or transporters elicits a strong response from the latter on the Tunisian side (roadblocks, strikes, damage to means of transport, etc.).

Thus, it falls to Tunisian Customs to resolve the disputes in part. This role, specific to Customs, is necessary in order for the Tunisian State to keep the peace in society, and to retain the support of the population. The role of Tunisian Customs officials is further complicated by the fact that sometimes they have no established, professional Libyan counterpart.

Guaranteeing the smooth flow of trade at the border by making Customs part of the security apparatus

Generally, despite the insecurity, Tunisian Customs is present at the border with Libya and plays an active role in the security apparatus. The situation in Tunisia is an interesting one as Customs has been able to reinstate its authority at the border after the border fell under military rule. This can be held up as an example that could be followed by other Customs administrations working in a fragile or insecure area.

On the basis of the Tunisian experience it can be said that making Customs, the only authority able to guarantee the smooth flow of cross-border trade, part of the security apparatus involves a number of elements:

- willingness by the central authorities to take into account the economic importance of the border;

- local Customs officers’ ability to send quantitative data, including data on seizures, back to the central authorities;

- the same means of force (weaponry, means of surveillance, etc.) as other security services;

- an understanding of local issues linked to cross-border trade by Customs officers who support commercial activity in the region in which they work.

On this last point, it should be noted that Customs officers, and probably the security forces as well, are well aware of their “social” role, and that they have not adopted a purely repressive approach to the trafficking of “legal” goods, other than weapons and drugs.

Appointing Customs officials that come from the region, applying more or less flat-rate taxation to small shipments, having border outposts that foster good relationships with the nomadic communities, and looking to take down the “big” smugglers (thereby breaking up monopolistic situations and allowing a greater number of “smaller fish” to do business) are all measures which, although technically simple, help to contribute to social peace, and encourage a favourable relationship between the population and the repressive apparatus of the State.

Food for thought

This WCO mission’s objective was not to run any diagnostics or to draft recommendations, but rather to make proposals with the aim of strengthening the position of senior Customs officials, and helping them to come up with a Customs policy that will ensure a balance between facilitation and security, taking into account the environment, priorities and means of the Tunisian Customs Administration, and one which would not necessarily be developed only in response to external recommendations. The proposals included:

- Organizing a debate on the possibility of establishing quicker and more reliable import, export or transit procedures at the border which would take account of current security challenges.

- Carrying out a quantitative study on the delays caused by security checks, particularly the scanner. It is highly likely that the delays linked to security checks, caused by the time taken for goods to be scanned, for example, are actually quite minor in comparison to the time it takes to get through the port. This type of quantitative study can demonstrate that security measures are compatible with facilitation.

- Adapting the anti-corruption policy to the security role. Corruption becomes a different issue as Customs plays an increasingly security-orientated role. On the one hand, by definition, terrorism-related fraud is a rarity in comparison to commercial Customs fraud. On the other hand, the perception that Customs is corrupt weighs heavily on non-corrupt Customs officials who cannot afford to take any risks when it comes to security checks: if a shipment to an armed or terrorist group is not checked, then the Customs official in charge would immediately be suspected of corruption, but if a risk-based security check procedure is in place, then a legal mechanism is needed to protect Customs officials. By the same token, an assessment system should make it possible to monitor the daily practice of Customs officials.

- Organizing a global seminar for senior officials in order to promote the development of in-house policies and techniques as well as better negotiations with external partners. Senior Customs officials do benefit from external expertise and training, particularly on facilitation instruments. The experience of Customs at the border post with Libya, however, shows that it is in the interests of each administration to develop its own solutions locally and show flexibility, both administratively and intellectually, in order to better understand and tackle problems. Moreover, the Customs officials that were met all showed a real desire to engage with the Customs strategy. It may also be interesting to note that Tunisian Customs organizes a seminar for its senior officials on topics of global interest relevant to Customs (facilitation, competitiveness, security, terrorism, corruption, tax, etc.) in order to encourage them to develop their own ways of thinking, and strengthen their negotiating skills for dialogue with foreign and international partners. This type of seminar, which is organized regularly, is both a platform for exchange and a source of motivation for senior officials.

- Organizing a workshop on Customs enforcement techniques in a desert environment. Different Customs administrations can share their experiences which would provide opportunities for perfecting border control strategies for such settings. It could be interesting to address the opposing concepts of managing the border like a “line” to defend and control through the use of a network of border outposts on the actual border, and managing the border as a series of cross-border “flows” to be controlled through surveillance concentrated at trade hubs where such flows meet.

- Carrying out a study of the “business model” of the various players involved in smuggling, across a number of flows of goods. Smuggling and the informal sector are supposed to provide goods at a low price to the poorest of the population. In order to assure the social function of smuggling, Customs agrees to apply advantageous fixed-rate tariffs to certain flows of goods, though there is a lack of data on this type of trade. It would be useful to know which actors along the value chain make the most profit. If it turns out that certain individuals are making significant profit, and that the quantities imported are grossly under-valued, a quantitative study would put Customs in a better position to negotiate with operators from the informal sector, making it easier to justify a change in fiscal policy.

- Carrying out a study on the links between smuggling and terrorism. It would be useful to study the transition process from one network to the other: how might couriers or smugglers become part of a terrorist network? What are the motives? How does it happen?

- Carrying out a study into the role of Customs at local level. The Tunisian experience, and this has been seen in other countries too, shows how important it is for Customs to participate in local government, as well as how important their role is in getting the population to contribute to ensuring their own security.

More information

research@wcoomd.org

capacity.building@wcoomd.org