Customs reform and trade facilitation in the Horn of Africa: Somaliland under the microscope

13 February 2017

By Creck Buyonge Mirito, CEO and Principal Consultant, Customs & International Trade Associates (CITA) LtdIntroduction

The Horn of Africa refers to the easternmost extension of Africa, and for the purposes of this article, includes the region covered by Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia, and Somaliland. This area has been a theatre of struggle between and amongst world powers for more than one century: the desire to control the Red Sea by colonial strategic interests; struggles for control over the waters of the River Nile among the riparian states, with some Nile River Basin countries questioning the relevance of the Anglo-Egyptian Agreement of 1929); ‘Cold War’ politics that saw countries in the region switching sides at different junctures; and, more recently, issues related to the ‘Global War on Terror.’

Interestingly, Article 10 of the Somaliland Constitution, which was adopted in 2000, recognizes, as part of the country’s foreign relations, that there has been “long-standing hostility in the Horn of Africa,” and that this needs to be replaced with “better understanding and closer relations.” This context informs issues relating to Customs and trade facilitation in the Horn of Africa generally, and in Somaliland in particular.

Somaliland has been cited as an example of locally-driven reconstruction in the period following the fall of Maj. Gen. Mohammed Siad Barre’s regime that ruled Somalia from 1969 to 1991. Siad Barre’s rise to power came in a bloodless coup after a police officer assassinated the then President, Dr Abdirashid Ali Shermarke, on 21 October 1969. On assuming power, Siad Barre adopted scientific socialism as the political ideology of the new state, with the justification that such an approach was not in contradiction with the tenets of Islam, and aligned himself with the Soviet Union.

In 1977, Siad Barre’s army invaded the Ogaden region of south-eastern Ethiopia, setting off a war that ended with the defeat of Somalia in 1978. He immediately changed his alignment to the United States for military support in exchange for American access to use Berbera Port. Siad Barre was also smarting from the failure of his long-standing war with Kenya – which began in the 1960s – over control of Kenya’s so-called Northern Frontier District that is inhabited by Somali-speaking and other related ethnic groups, such as the Borana, Burji, Garre, Ajurran, and Degodia.

War broke out in 1988 between the government and secessionist guerrillas from the north, known as the Somali National Movement (SNM), who contended that they had been systematically discriminated against by Siad Barre’s government. After the government was overthrown in January 1991, the SNM took control of north-western Somalia and unilaterally declared independence from the rest of Somalia to become the new ‘Republic of Somaliland,’ defined by the borders of the former British Protectorate. This was reaffirmed at a conference in Burco (April/May 1991) and in Borama (May 1993).

The complex relationship between Somaliland and Somalia partly arises from the fact that the former British Somaliland gained independence and became a sovereign state on 26 June 1960, but chose to enter into a union with Somalia on 1 July 1960. But, as we have seen, the union ended in 1991 after a civil war that started in 1988 due to long-standing grievances over discrimination by the Somalian regime.

The new Republic of Somaliland has not received international recognition in spite of it having all the key elements of a modern state, such as a defined territory, a stable government, and a Constitution. Its success in state-building is partly attributed to the fact that it has integrated traditional ways of governance, which are based on consultation and consent, with the apparatus of a modern state. Establishment of an effective and efficient Customs administration is a contribution towards building a sustainable Somaliland state.

Delayed recognition of Somaliland’s sovereignty means that the country does not belong to any regional or international organizations. However, this has not prevented it from exercising some functions associated with sovereign states, such as the negotiation of agreements with other states. In this regard, Somaliland has a transit and trade facilitation agreement with Ethiopia, and in mid-2016, agreements were signed between the Berbera Port Authority (owned and operated by the Republic of Somaliland) and DP World (the Dubai-based global maritime port terminal operator), providing for a 30-year concession for Berbera Port, and the establishment of duty free zones.

These developments, as well as the decision to create a revenue authority in the near future, mirror what is happening elsewhere in the Horn of Africa, such as the establishment of the Djibouti Duty Free Zone, or the coming into existence in 2008 of the Ethiopian Revenues and Customs Authority (ERCA) – a merger between the Ethiopian Customs Authority and the Federal Inland Revenue Authority.

In addition to political instability and geopolitics, the Horn of Africa region has also been shaped by complex ethnic and clan dynamics, especially in the Somali-speaking countries of Djibouti (colonial era French Somaliland), Somalia (colonial era Italian Somaliland) and Somaliland (colonial era British Somaliland).

The major clans in Somaliland include the Isaaq, Gadabuursi, Ciisa, Dhulbahante and Warsangeeli, and clan membership is taken into account in the distribution of government positions, rather than pure meritocracy. In spite of Somaliland having been a former British Protectorate, it did not inherit the sort of bureaucracy usually associated with Commonwealth member countries, as there was an overlay of practices associated with the Italian system of governing, introduced during the union period which ran from 1960 to 1991.

Context for reform

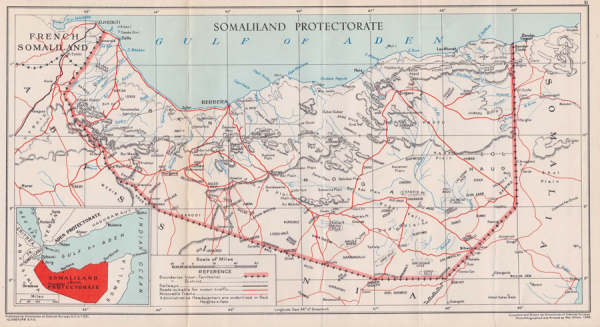

Article 2 of the Constitution of Somaliland clearly defines the territory of Somaliland in terms of location (“between latitude 8° to 11° 30’ north of the equator and longitude 42° 45’ east; and consists of the land, islands, and territorial waters, above and below the surface, the air space and continental shelf”) and borders (“the Republic of Somaliland is bordered by the Gulf of Aden to the east; the Federal Republic of Ethiopia to the south and the west; and the Republic of Djibouti to the north-west”).

In terms of Article 6, “the official language of the Republic is Somali, while the second is Arabic, and other languages shall be used when necessary.” Furthermore, Article 14 (paragraph 1) provides that “no taxes or duties which have not been determined by law shall be collected,” and that “the levying, waiver and changes in taxes and other duties shall be determined by law.”

Customs reform in Somaliland is being undertaken as part of the government’s Public Financial Management (PFM) Strategy, which was launched in 2011. During the launch, the then Minister for Finance, Eng. Mohamed Hashi Elmi, identified the four key challenges in raising revenues for the country:

- a lack of capacity in the tax administration system, and low compliance levels among taxpayers;

- a need for tax law and tax administration reform, and a development-oriented system of taxation;

- the difficulty in taxing the dominant pastoral and informal economy;

- the need to fight corruption, as the tax administration is widely perceived to be corrupt.

Customs and revenue reform is also in line with the Somaliland National Development Plan (2012-2016) which focuses on reform of the Ministry of Finance through strengthening revenue policies and systems, reviewing and updating all procedures related to the Customs and Inland Revenue Act, introducing and enforcing value-added tax (VAT) and establishing a training centre for the Ministry. A government-wide Civil Service Strengthening Project, supported by World Bank “with the overarching goal of strengthening institutions to deliver services to citizens” according to Country Representative Hugh Riddell, was launched in November 2016.

Five years after the launch of the PFM Strategy, Customs Law No. 73 was adopted on 16 July 2016, repealing the Customs Rules and Procedures Law No. 91/96. This was a critical step in Somaliland’s reform process. As WCO Secretary General Dr Kunio Mikuriya said in 2005, “without an effective legal framework that guarantees transparent, predictable and prompt Customs procedures, the international private sector will find it highly cumbersome to conduct business with, or invest in, a country in a competitive business environment” (Customs Modernization Handbook, p. 51).

The repealed law provided for the classification of goods based on the Convention on Nomenclature for the classification of goods in Customs tariffs (1959), Customs valuation using the Brussels Definition of Value (1953), the coordinating role of Customs at the border, and anti-smuggling measures. This is in contrast to the new law which provides for the use of the WCO Harmonized Commodity Description and Coding System (HS Code), the Valuation Agreement of the World Trade Organization (WTO), and modern Customs procedures that include risk management and post-clearance audit.

Moreover, and just as equally important, Revenue Act No. 72 of 2016 made provision for the establishment of the Somaliland Revenue Authority (SLRA), and makes fundamental changes to the administration of tax law in Somaliland.

Customs and trade facilitation challenges and reform initiatives

Somaliland faces a number of challenges related to Customs and trade facilitation. First and foremost, though the Somaliland Constitution requires a legal basis for the collection of duties and taxes, the intermingling of international norms which are not always well understood, and the cultural tendency to negotiate and consult on everything, leads to unpredictability in the international trading environment.

Even when the current law provides for the use of international standards (such as valuation methods based on the WTO Valuation Agreement, or goods classification based on the HS Code), the understanding of these standards tends to be localized and country-specific. For example, the General Rules for Interpretation of the Harmonized System may be used and interpreted selectively, with an eye to increasing revenue rather than the strict application of the HS rules and the provisions contained in national law.

To remedy this situation, workshops on Customs law, rules of origin and Customs valuation were held in 2015 and 2016 for technical officers and managers from the Ministry of Finance, as well as relevant stakeholders. The objective being to create a sound foundation for Customs operations, based on simple, clear and predictable rules. These workshops were held at three locations, namely Berbera, Burco and Borama.

There is also a need to enhance strategic and operational planning capacity in the Ministry of Finance, in the envisaged SLRA, and, more specifically, in the Customs Department. In this regard, a Tax Policy Unit (TPU) has been established and staffed, under the Strengthening Revenue Policy and Administration in Somaliland Project (2015/16), funded by the Department for International Development (DFID) in the United Kingdom (UK).

Technical assistance delivered under the DFID-funded project includes development and training in the use of a revenue forecasting model. A comprehensive national strategy for a modern Customs and revenue administration has also been developed, validated and adopted. At a workshop in October 2015, Customs managers adopted the following principles for a modern Somaliland Customs administration: integrity (sharaf/hufnaan); fairness (daacadnimo); transparency (daah-furnaan); mutual respect and cooperation (iskaashi-shaqo/talo-wadaag); and professionalism (aqoon-xirfadeed).

In addition, successful reform requires appropriate project management structures, and several have been established:

- a PFM Coordination Unit;

- a Revenue Reform Steering Committee (RSC) chaired by the Minister for Finance, which meets monthly, and which includes representatives of DFID and the implementing partner, the Director General in the Ministry of Finance, the PFM Coordinator, and Directors from the Inland Revenue, Customs and Planning Departments;

- a Revenue Technical Working Group (RTWG), which meets weekly to monitor project progress and address any bottlenecks that may be encountered;

- a Customs Reform and Modernization Committee (CRMC), at departmental level, has been established as the focal point for the identification of the needs and reforms in the Department.

Without adequate cooperation, communication and partnerships with external stakeholders in the public and private sector, Customs reforms can easily encounter conflict and lose steam. Training and sensitization provided under the DFID-funded project has, therefore, included representatives of the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, the Berbera Port Authority, the Somaliland Chamber of Commerce & Industry, the Quality Control Commission, the Central Bank of Somaliland, and the Accountant General among others. This partnership approach is reflected in the concept of ‘iskaashi-shaqo/talo-wadaag’ (mutual respect and cooperation).

Conclusion

Customs reform and trade facilitation in a post-conflict environment like Somaliland has its special challenges, but as we have seen, efforts are being made to address these challenges comprehensively through strategic and policy interventions, as well as through implementation at the operational level.

Nevertheless, it will take time to enhance the capacity of the country to operate a modern Customs and revenue administration with adequate structures, including the necessary human and financial resources. On the positive side though, the support of development partners has certainly provided the needed impetus for Customs and revenue reform and modernization, but more needs to be done. Somaliland is the definitely on the right track!

More information

creckbuyonge@gmail.com

Creck Buyonge Mirito is the CEO and Principal Consultant of Customs & International Trade Associates (CITA) Ltd., which is based in Nairobi, Kenya. CITA engages in training, research and consultancy on Customs, international trade, trade facilitation and border management issues. From September 2015 to December 2016, Mr Mirito worked as a Customs Policy and Training Expert in the “Strengthening Revenue Policy & Administration in Somaliland Project,” which was funded by the UK’s Department for International Development and implemented by Adam Smith International. The views expressed in this article are his own.