Reviewing the OECD method to assess trade facilitation policies

16 October 2018

By Xiaoping Jiang, Director, and Zhuojian Zhou, Project Manager, Re-code Trade Security and Facilitation Research Center, ChinaRe-code, an independent Chinese research institute focusing on issues related to Customs and trade, shares its thoughts in this article on the OECD method to assess trade facilitation policies, explains why it decided to evaluate the performance of China using the indicators constructed by the OECD, but not the same scoring methodology, and what the exercise revealed.

Several international organizations have developed methods to assess the efficiency of countries in facilitating trade flows. Among them are the World Bank with the Doing Business project and the Logistics Performance Index, the World Economic Forum who publishes the Global Trade Enabling Report and the Global Competitiveness Report, and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) with its set of Trade Facilitation Indicators. This last method forms the focus of this article.

OECD assessment method

The OECD developed indicators to assess the extent to which countries have introduced and implemented trade facilitation measures as well as their performance relative to others. The measures that were selected are specific or “narrow,” focusing on public prerogatives, and drawn from the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) Trade Facilitation Agreement.

There are 11 first-level indicators related to the import/export procedure, each of which is subdivided into further indicators: 115 in total. The methodology is by no means complicated: the score for each first-level indicator is the average of the scores obtained for each of the second-level indicators (i.e. the subdivisions), while global trade facilitation performance is the average of the scores of the first-level indicators.

There are two methods to calculate the score of the second-level indicators:

- “Direct scoring” – Indicators are scored from 0 to 2 (0 for poor performance, 1 for average performance, and 2 for good performance) on the basis of the results of an investigation. Investigators may rely on publicly available sources of information (Customs websites, official publications such as Customs codes, etc.), and on questionnaires replied to by the relevant administrations and by carriers with a worldwide presence.

- “Indirect scoring” – Data is extracted from existing international reports, databases or other sources, and is translated into corresponding scores based on specific rules.

For more details about each indicator, the data sources and the method of calculation, see the online tool “Trade Facilitation Indicators Simulator”.

China’s trade facilitation policies

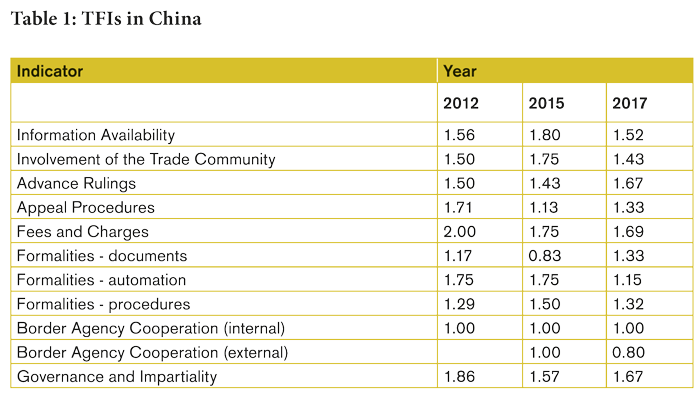

The OECD conducted assessments on China’s trade facilitation policies in 2012, 2015 and 2017.

The results are shown in table 1.

Experts agreed that, in general, the above evaluation results fairly reflected the level of trade facilitation in China. However, a great many trade experts also thought that several of the indicators were not assessed well enough and, therefore, deviated from the reality on the ground.

An example is the assessment done in 2017, in particular the indicator referring to the pre-entry advance ruling programme, which allows China Customs to provide decisions on the classification, origin and valuation of commodities prior to their importation or exportation. Re-code believes that the performance of China in this respect is not deemed to be as good as the OECD’s estimate indicates. The score obtained seemed too high for two reasons:

- provisions regulating advance rulings in classification, valuation and origin of commodities are not well harmonized with other relevant regulations;

- the procedures and the requirements to issue a ruling are not standardized or unified across the country.

Another example is the score attributed to the three indicators falling under “Formalities,” which seemed to be undervalued. It is widely recognized that China has made tremendous progress when it comes to formalities: documentation requirements and Customs procedures have been simplified to a great extent and information technology (IT) systems have been improved, allowing for far more automation. While this progress has been recognized by the trade community in China, it is not reflected in the assessment conducted by the OECD.

The scores of the two indicators related to “Border Agency Cooperation” also do not seem to conform to reality. Over the past few years, China Customs has spared no efforts to promote cooperation with staff of the Chinese General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine (AQSIQ)[1]. In addition, an “inter-agency licence verification network” has been developed with other authorities. Cooperation with foreign counterparts has also improved, with Chinese agencies being very proactive in this domain. For example, China Customs has initiated a number of joint control programmes with the Customs administrations of several neighbouring countries. These efforts are not properly reflected in the OECD assessment.

Causes of deviation

Re-code believes that there are three major reasons for the deviations observed on some indicators.

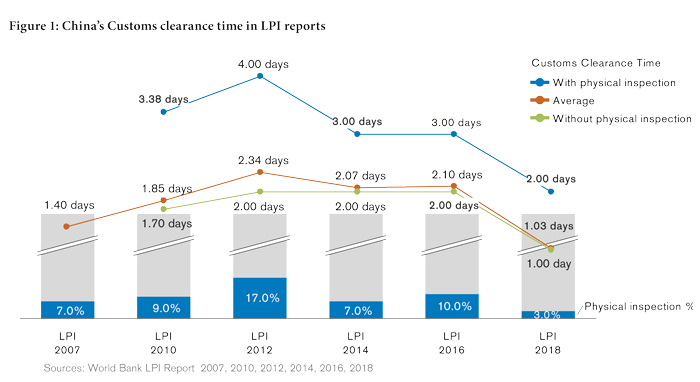

The first has to do with data sources. Many second-level indicators are calculated using the indirect scoring method, i.e. data from reports or databases of other parties. The problem is that this data is sometimes defective. Let’s take the figure related to “Clearance Time,” a subcategory indicator under “Formalities – Procedures,” as an example. The OECD uses a clearance time without physical inspection and the clearance time with physical inspection published in the World Bank’s Logistics Performance Index (LPI) to determine the value of this indicator. The figures obtained from the 2014 and 2016 reports show no real progress in this regard. Average clearance times are 2.07 and 2.10 days respectively.

However, China has taken many measures to optimize clearance formalities, with trade-related border agencies working together to expedite procedures and inspections. Progress was reflected in several Time Release Studies that Re-code conducted in China since 2014 (see the report on the study undertaken in 2015 published at the end of this article in the digital edition of the magazine). In addition, the figures on clearance times, extracted from the Customs clearance management system to which Re-code had access in 2016, are much lower than those reported in the LPI.

Thus, there are reasons to doubt that the data in the LPI reflected clearance time properly in 2014 and 2016. Since the OECD published its latest TFIs in 2017, the World Bank released its 2018 LPI which does reflect great improvement in the clearance time. The evolution of the clearance time as reported in the LPI over the years is shown in Figure 1.

Another issue is that the scoring method does not sometimes allow progress made to be appreciated. Let’s once again take the clearance time as an example which is scored following a binary methodology, with a range of 0 to 2, with thresholds based on the above/below average method. The indicator is scored 0 when the country’s “average clearance time” in the LPI ranks among the lowest scores obtained by 30% of the assessed economies, 1 when it ranks among the scores obtained by 40% of the following economies, and 2 when it falls under the highest scores obtained by the remaining 30% of economies. If the ranking of an economy stays in the same demarcated range, even though there is a big jump in ranking compared with the previous report, its OECD’s score will remain unchanged.

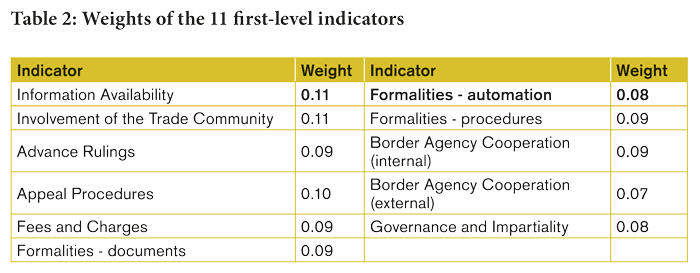

Finally, the OECD uses unweighted formulas to calculate the scores of the 11 first-level indicators. In this respect, Re-code believes that conducting the assessment simply by calculating an average without setting weights and taking into account the difference in importance of the indicators as well as their possible correlations (correlation between variables could be interpreted as double counting) is not optimal.

Reviewing the OECD methodology

Re-code has made relevant adjustments and improvements to tackle the deficiencies mentioned above. Instead of relying on publicly available data as well as reports and databases developed by other international organizations, the Research Center decided to set up a pool of experts, and asked them to score each second-level indicator. To ensure the impartiality of the results, Re-code set some conditions when hiring the experts. They had to be engaged in the business of trade, had to have more than five years of trade-related experience, and had to be interested in trade facilitation in China as well as willing to take part in the assessment.

In 2017, 21 experienced experts from governmental agencies (including China Customs and the Chinese General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine), from the trade community, and from independent research institutes were invited to participate in the survey.

Weights were assigned to indicators during the aggregation process in order to reflect the specific importance of some indicators and to reduce the impact of the potential correlations among some of them. Re-code asked the three most senior experts to evaluate the importance of each first-level and second-level indicator and to then set a corresponding weight according to the results of their evaluations. The weights of the first-level indicators are listed in Table 2.

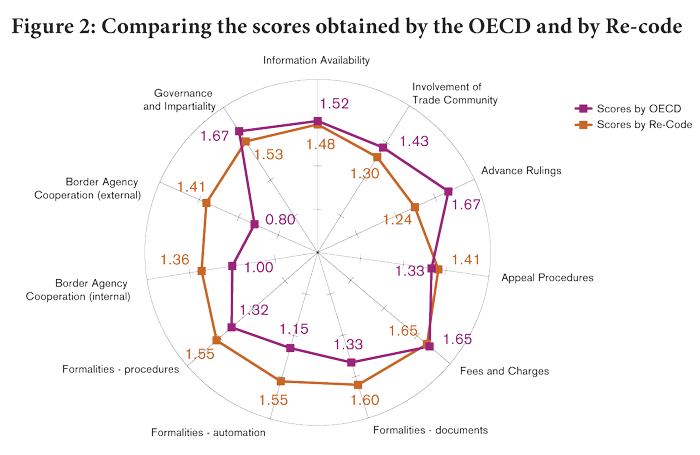

With the above adjustments and improvements, a new set of scores on the 11 first-level indicators was developed, which are compared with the conclusions of the 2017 TFIs assessment by the OECD in Figure 2.

Research results

The results of the research were published in Re-code’s “Annual Report on Trade Facilitation of China 2017,” with readers being encouraged to send their feedback on the research findings.

On the positive side, some found that Re-code’s research provided a more accurate assessment of the actual trade facilitation performance of China than the one done by the OECD, and that the progress made in China when it comes to formalities and international/national cooperation was better reflected.

On the other hand, some deficiencies of the Chinese government were also exposed, especially in relation to the management of advance rulings and consultations involving the trade community when introducing or amending trade related laws, regulations and administrative rulings of general application.

More information

Recode reports can be downloaded at https://pan.baidu.com/s/14Urcz5vKDhSp7S9lRBs4CQ

[1] In March 2018, the AQSIQ was dismantled under a government restructuring programme, and its entry-exit inspection and quarantine duties and workforce have been integrated into China Customs.