How United States customs scientists at the border are stemming the flow of opioids and other dangerous drugs

21 June 2022

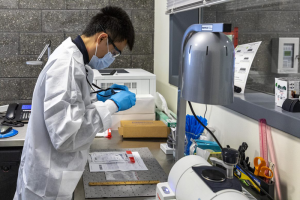

By Marcy Mason, Writer, US Customs and Border ProtectionFive years ago, when the United States started to see a rapid rise in opioid overdose deaths, U.S. Customs and Border Protection was encountering large quantities of an unknown substance arriving in international mail and express courier shipments at the U.S. ports of entry. CBP officers suspected it was an illicit drug. They attempted to use tools to identify the substance, but the technology was limited. Novel drugs that had never been identified before were not in the equipment’s library and the tools wouldn’t work. The suspected substances were sent to scientists at CBP’s regional labs where they were identified as fentanyl, a highly dangerous, addictive opioid narcotic. But identifying the drugs at the regional labs was a slow and inefficient process for mail and express shipment environments. So CBP’s Laboratories and Scientific Services came up with an innovative solution—locating lab scientists on-site at the U.S. ports.

Timing is everything when it comes to stopping the flow of illicit drugs from entering the U.S. That is why five years ago, when the country was in the throes of the opioid crisis, with more than 47,600 overdose deaths in a single year, U.S. Customs and Border Protection located agency laboratory scientists on-site at the U.S. ports of entry. The scientists were part of a special operation known as Operation Sustain, which was designed to stem the flow of fentanyl and other narcotics found smuggled in shipments at international mail and express courier facilities. The faster the scientists could analyze the suspected drugs, the quicker CBP officers could seize and destroy the white powdery substances or work with other agencies such as Homeland Security Investigations, HSI, to make law enforcement-controlled deliveries that could potentially lead to arrests and shutdown dealers and their networks.

In late October 2016, when CBP Officer Tom Pagano started working at the international mail facility at John F. Kennedy International Airport in Queens, New York, where 60% of U.S international mail is processed, there weren’t any scientists working on-site. It was also the first time Pagano encountered fentanyl. “I had never heard of fentanyl. When we started finding it, I was curious. I thought, ‘What is this stuff?’” said Pagano. “After we found it a few more times, we were warned, ‘Hey, watch out. This drug is deadly.’”

Pagano and the other CBP officers at the international mail facility had tools to test the unknown substances for an initial or presumptive analysis, but the technology was limited. If a substance had never been identified before, the tools weren’t able to match it with drugs that were part of the equipment’s library. Instead, the officers collected and sent samples of the suspected drugs to a CBP regional field laboratory. The field labs would place the samples in a queue where they waited with other samples that needed to be tested. After the scientists analyzed the samples, they would send the results to the officers. It was a lengthy process that could take anywhere from 30 to 45 days for a presumptive analysis and six months to two years for confirmatory final results.

“I was able to look for drugs as much as I wanted, but the labs weren’t ready for that because I was finding so much. I could just walk into the mailroom and select 10 parcels and all 10 of them had drugs in them,” said Pagano. “I was only allowed to submit 20 samples a day, but there were times that I would find 200 or 300 packages with suspected drugs. They would have to wait to be processed. It was creating a backlog and we couldn’t store the packages anywhere.”

For a while, a CBP scientist was assigned to work at the international mail facility one day a week. “If we had samples we believed were fentanyl, we would give them to him,” said Pagano. “When he was on-site, he was able to tell us presumptive findings right away. But if we found something on a day he wasn’t there, we would have to wait for him to do the tests to possibly get an answer. If he took a day off, it could be two weeks before we would hear anything back on what the substance was.”

Pagano and the officers started to notice that as opioid deaths continued to rise so did the number of interceptions at the JFK international mail facility. “We kept seizing more and more parcels containing narcotics. And it wasn’t just fentanyl. It was every drug imaginable,” said Pagano. We seized LSD, PCP, marijuana, magic mushrooms, bath salts and other synthetic designer drugs. Basically, any illicit drug you can think of was coming through there and we were finding it.”

Fentanyl on the rise

The port of Memphis, where the FedEx Express World Hub is located, was wrestling with similar issues. As early as 2014, when U.S. trade increased with China, CBP officers started noticing unknown substances in shipments. “We started seeing an increase in international freight on direct flights from China and Hong Kong. With the increase, we began seeing unknown powders and liquids,” said Lori Breakstone, who was CBP’s assistant area port director for Memphis at the time. By 2016, there was a substantial uptick. “Until that time, we were finding traditional narcotics such as cocaine, heroin, meth, marijuana, hashish. We were not used to seeing fentanyl or synthetic opioids,” said Breakstone. “When we first started to see fentanyl, we had no idea what it was. We had never seen anything like it before.”

Similar to the JFK international mail facility, the port of Memphis did not have a permanent lab on-site or the tools to identify fentanyl. “We had to package up the samples individually, mail them to CBP’s Houston regional lab, and then wait for results,” said Breakstone. “As we started detaining more and more shipments, the Houston lab could not keep up and we couldn’t keep up on our end.”

The shipments were held in a storage area until the sample results came back from the lab. “It would take weeks, months, sometimes over a year for a determination. On average, we had 400-600 shipments sitting on the shelves,” said Breakstone.

The long wait impacted enforcement actions. HSI was reluctant to take the seized shipments for controlled deliveries and turned most of them down. “We were making seizures and stopping narcotics from entering the U.S., but we weren’t disrupting the drug flow,” said Breakstone. “Investigators weren’t given a chance to break the network and dismantle it overseas where the shipments were originating from. The timing of an investigation ties in heavily with the lab. It’s critical in an express environment. If a package is not delivered, drug dealers know something is wrong.”

Breakstone reached out to CBP’s Laboratories and Scientific Services to make a plea for an on-site lab. Pagano had already done the same for the JFK international mail facility. In June 2018, Operation Sustain was launched at both locations. “This was our response to the opioid crisis,” said Patricia Coleman, deputy executive director of CBP’s Laboratories and Scientific Services. “We detailed scientists at the JFK international mail facility and the Memphis FedEx Express hub to see how effective it would be to provide on-site support for our officers when they interdicted unknown substances.” The operation, which ran through September 2018, was an immediate success and led to the creation of forward operating labs, where permanent CBP forensic scientists were hired to perform on-site scientific analysis at ports of entry.

Within weeks of Operation Sustain’s startup, in July 2018, a shipment manifested as an “organic pigment set” arrived from China at the FedEx Express hub in Memphis. Inside the package was a makeup jar filled with an unknown white powder. An on-site CBP forensic scientist tested the substance and identified the powder as butyryl fentanyl, a potent synthetic opioid found in overdose deaths. “We tested the substance and seized it the same night,” said Chief CBP Officer Victor Watson, who oversees CBP’s operations at the FedEx Express hub. “It took 10 minutes for the on-site lab to identify that the substance was butyryl fentanyl.”

The lethality of fentanyl is a major concern. “Until the on-site lab was set up, we did not know how dangerous this drug is,” said Watson. “Even a small amount of fentanyl is deadly. We were examining shipments that were almost 100% pure fentanyl, so the lethality was huge. An officer who opens a package not knowing that it’s fentanyl could accidentally touch or ingest it, putting his or her life at risk,” explained Watson. “By having the lab here, we’re able to identify that it’s fentanyl and follow the safety protocols we have in place to quickly contain it. Having a scientist on-site has been a significant safety enhancement for our front-line officers.”

Hitting pay dirt

The on-site lab also increased the potential for controlled deliveries to make arrests. Officers could make quick enforcement decisions, which is paramount in an express mail environment. “For FedEx, this is the main international sorting facility. It’s one of the top five largest cargo airports in the world by volume,” said Watson. “Each night, approximately 250,000 pieces of international cargo flow through the facility in a 4-1/2 to 5-hour time frame, which means our officers only have a narrow window to inspect and clear packages before shipments are routed on to their next destination. If flights are delayed, businesses will be disrupted. So the timing of targeting and testing shipments is critical for the success of controlled deliveries.”

One stunning example that illustrates how vital an on-site lab can be occurred in September 2020, when a shipment from China, manifested as 1.5 kilograms of “silicon dioxide,” or sand, was selected for examination at the Memphis FedEx Express hub. “The shipment did not make sense to me,” said Michael Hughes the CBP officer who targeted the package that was valued at $10. “Am I going to spend $10 to order 3-1/2 pounds of sand from China when the airway bill cost more than that? Why would you do it? It just didn’t make sense.”

Inside the package, the CBP examining officer found a small, silver bag that contained a white powdery substance. He took it to the on-site CBP scientist who tested the substance and quickly discovered it wasn’t sand. It was xylazine. “Xylazine is a sedative for farm animals. It’s approved for veterinary use, but it’s not FDA approved for people,” said Shelby Stotelmyer, the lead forensic scientist at CBP’s Memphis forward operating lab. “Drug traffickers use it as a filler agent for heroin, fentanyl, and other narcotics to increase the amount they can sell and for enhancement effects.”

The package was seized and HSI in Memphis was notified to see if agents were interested in making a controlled delivery. Stotelmyer sent the results with her daily report to headquarters. In Washington, scientist Michael McCormick from the White House’s Office of the National Drug Control Policy and a liaison to CBP, studied the report and flagged it. “Our law enforcement partners in New Jersey had been reporting large quantities of xylazine showing up in the toxicology of heroin and fentanyl overdose victims, and this shipment was destined for Philadelphia, which is a hop, skip, and a jump from New Jersey,” said McCormick, who passed the information to CBP’s National Targeting Center to see if there was any other derogatory information associated with the parcel, the shipper, or the receiver. “The National Targeting Center looked into it,” said McCormick, “and referred the case to HSI for further investigation.”

In Philadelphia, the case caught the attention of Ryan Landers, an HSI supervisory special agent who oversees a cybercrime investigation task force that mainly investigates drugs smuggled on the darknet. Landers was acutely aware of the trending intelligence regarding xylazine and decided to take action. “Normally, we wouldn’t take a case like this,” said Landers. “Controlled deliveries typically involve a controlled substance such as illicitly used drugs or prescription medications regulated by the government. Xylazine is currently not a controlled substance in the United States, so we took an unconventional approach and executed a controlled delivery with a non-controlled substance.”

Landers’ team delivered the FedEx Express parcel containing the xylazine at the address listed on the manifest and conducted surveillance. Shortly thereafter, an individual arrived at the location in a vehicle and retrieved the parcel. HSI special agents followed the individual to a home at a second address and established surveillance there. Later that day, the individual emerged from the residence in a highly suspicious manner and drove away in his vehicle. Local law enforcement, working in tandem with HSI, detained the individual at a traffic stop and searched the vehicle.

The payoff was huge. The individual, a convicted felon, was arrested and HSI and the state police seized nearly 6 pounds of fentanyl, a stolen, untraceable firearm with a sizeable amount of ammunition, a large quantity of U.S. currency, and the original shipment of xylazine that was delivered to the first address. “To take a non-controlled substance and link it to a deadly fentanyl-based drug distribution network is unusual,” said Landers. “This case is significant for both HSI Philadelphia and on a grander scale for the war on drugs.”

The lab’s role was also significant, said Landers. “The on-site labs are critical to what we do. The speed and nature of their ability to test is crucial to the investigative integrity of a case,” said Landers. “If something is lagging at a port of entry for weeks and months, from an investigative standpoint, that lead is dead.”

Likewise, Landers credited the success of the case to HSI’s partnership with CBP. “HSI can do very little without the partnership of CBP. Whether it’s the Office of Field Operations or the scientists at the forward operating labs, we are tied to a cooperative and collaborative working relationship with CBP on a daily basis,” said Landers. “When we’re investigating international drug smuggling or importations, it’s imperative that we work hand in hand with the officers who are on the front line at the border inspecting the commerce that comes in and out of the country. They are our eyes and ears on the front lines of that port of entry. We can’t do what we do without that relationship and partnership.”

Labs at high-risk locations

By 2019, CBP’s Laboratories and Scientific Services fully embraced the concept of having scientists on-site at forward operating labs and began establishing more labs at high-threat locations. Many were along the Southwest border, but also in locations such as Chicago, Miami, Detroit, Los Angeles, and Puerto Rico. CBP currently has 14 forward operating labs in operation.

The on-site labs provide multiple benefits including helping CBP identify trends. For example, starting in October 2020, the forward operating labs began seeing an increased amount of N,N-dimethyltryptamine or DMT, a hallucinogenic drug, smuggled across the border. “DMT has been the No. 1 drug seen at CBP’s forward operating laboratories. We’ve seen it coming from South America,” said McCormick. “Once we spotted it, we told our state and local partners, so they could have appropriate standards in place for detecting this material in their street drugs.”

Another trend that the forward operating labs recently discovered is a new fentanyl analogue coming across the Southwest border. A fentanyl analogue is a drug designed to mimic the pharmacological effects of fentanyl, but its molecular structure is just different enough that it is not detected in standard drug tests and can evade legal restrictions on banned substances. “Fentanyl analogues are starting to trickle in from Mexico,” said McCormick. “We don’t know a lot about them pharmacologically, but they are likely to be as dangerous or more dangerous than fentanyl. What is unique is that this particular analogue was once seen coming from China, but after there was a class ban on fentanyl analogues in 2019, prohibiting anything with the fentanyl core structure from entering the U.S., the analogue shipments from China dropped to nearly zero. So it was strange to suddenly see fentanyl analogues coming in from Mexico.”

The forward operating lab at the port of Nogales, Arizona, on the border of Mexico, was one of the first labs to note the trend. Before the coronavirus pandemic, methamphetamine was the predominant drug smuggled into the port. But in March 2020, when non-essential travel was restricted on the U.S.-Mexico border to prevent the spread of COVID-19, scientists at the port saw a shift take place. “At the end of March 2020, we didn’t see any narcotics. It was almost like the cartel took a week off to regroup. But then we started to see more and more fentanyl coming across the border,” said scientist Terra Cahill, a special advisor to CBP’s Laboratories and Scientific Services who was working at the lab in Nogales. “In January 2020, 46% of the samples we tested were meth and 18% were fentanyl. But by March 2021, the number of fentanyl samples had more than doubled, representing 52% of all the samples we tested.”

Cahill said the shift was attributed to the border restrictions. “Meth seizures were generally taken from vehicles driven by Mexicans, but the cartel lost that opportunity,” said Cahill. “U.S. citizens became the drug mules because they had access to come across the border. They were mostly body carriers, so they were carrying the drugs somewhere on or inside their bodies.”

Seeing the big picture

According to Coleman, information flowing from the labs allows CBP to see the big picture. “We can identify what’s coming at us faster and better than we have historically been able to do,” she said. “Before it could be weeks to several months before we uncovered exactly what was interdicted by the CBP officers. So it delayed information gathering, intelligence reporting, and whether or not we’re going to prosecute someone. The faster our scientists can provide lab results, the better we are going to be at addressing the threat coming at us—whether it’s drug smuggling, terrorist activity, or any other threat to the homeland.”

Furthermore, nothing is static, said Coleman. “Drug smuggling is a constantly changing environment and through the real-time information gathered from the forward operating labs, we’re able to figure out things that would have taken us years or we might not ever have figured out because we wouldn’t be looking at this issue from the lens that we’re looking at it today,” said Coleman.

With scientists on-site, officers can focus more fully on their law enforcement duties and legitimate shipments can move faster too. “The forensic scientist we have here is very good and very fast. I can give her a substance and most of the time she can test it and know what it is within 20 seconds, and that’s no exaggeration. She’s that quick,” said Hughes, the CBP officer at the Memphis FedEx Express hub. “If it’s a legitimate shipment that we’re looking at, it’s on its way that night.”

The scientists are also an integral part of outmaneuvering drug traffickers. “Smugglers are innovative. They use creative methods to hide drugs,” said Stotelmyer. “The other night the officers brought honey to the lab for me to test because they don’t have the equipment to distinguish the difference between the drug and the substance it was hidden in.” Stotelmyer extracted the drug, sildenafil citrate, using different solvents to dissolve the honey. “It’s the erectile dysfunction drug used in Viagra,” said Stotelmyer. “The same way smugglers are coming up with creative ways to conceal these illicit drugs, we have to be creative as scientists to forensically unmask them.”

More information

www.cbp.gov