Tobacco Control, International Trade, and Public Health: a review of Holly Jarman’s book ‘The Politics of Trade and Tobacco Control’

28 October 2015

By Robert Ireland, WCO Head of Research and CommunicationsIntroduction

International trade is subject to conflicts that can arise from, among other things, the inherent tension between business profits and governmental protection of health, safety and the environment. Topics such as plain (standardized) packaging of cigarettes; asbestos (the European Communities – Measures affecting asbestos and asbestos-containing products case); and carbon tariffs (border tax adjustments) in the context of global warming have faced such debate and conflict.

The World Trade Organization’s (WTO) core principle for resolving these clashes is in the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade’s (GATT) Article 20 (General Exceptions), which provides that WTO Members can “protect human, animal, or plant life or health” if “such measures are not applied in a manner which would constitute a means of arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination between countries where the same conditions prevail, or a disguised restriction on international trade.”

The trade in tobacco is a classic public policy example of this dynamic. With respect to public health, cigarettes are unique in that they are the only product that currently can be sold and bought legally but harms the user if consumed as intended. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), six million people died in 2014 from smoking-related diseases; one billion people, mostly in developing countries, are projected to die from smoking-related diseases over the course of the 21st Century.

The trade in tobacco is a classic public policy example of this dynamic. With respect to public health, cigarettes are unique in that they are the only product that currently can be sold and bought legally but harms the user if consumed as intended. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), six million people died in 2014 from smoking-related diseases; one billion people, mostly in developing countries, are projected to die from smoking-related diseases over the course of the 21st Century.

In addition to their inherent carcinogenic toxicity, cigarettes have the added health detriment – albeit a business advantage to the tobacco industry – of being a highly addictive product which makes cessation a tall obstacle to overcome. On the business side, the tobacco industry grosses enormous amounts of money and employs many workers. An ongoing societal choice is thus whether to prioritize the interests of those who profit from tobacco sales or global public health.

National tobacco control regulations seek to protect human health by restricting all cigarette brands, not just a few chosen ones. In addition to higher tobacco taxes (collected by Customs and other revenue agencies), advertising restrictions and smoking bans in public places, limiting the advertising on cigarette packs with plain packaging is currently at the frontline of tobacco-related public health policymaking. Four countries – Australia, France, Ireland and the United Kingdom – have thus far adopted plain packaging.

Tobacco companies are litigating against plain packaging and are doing so not based on the WTO Article 20 principles but by contending that cigarette pack advertising and logos are trademarks and property rights, and should be protected under the rubric of intellectual property rights and ownership in general.

The Politics of Trade and Tobacco Control

The 2015 book ‘The Politics of Trade and Tobacco Control’ by Dr. Holly Jarman, a political scientist at the University of Michigan in the United States, examines the intersection of public health, tobacco control and international trade. In addition, the book describes how lawsuits are being used to challenge public health laws, both in national courts and also in international trade tribunals.

Legal actions against plain packaging laws

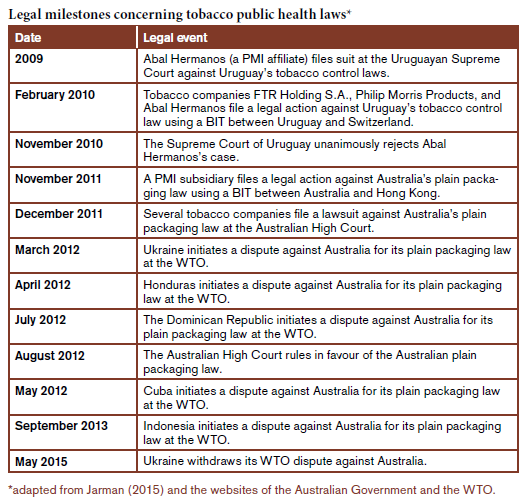

Plain packaging and similar tobacco control laws have been subjected to legal actions in three different types of legal forums: (1) national courts; (2) ad hoc tribunals established using provisions from trade or investment agreements; and (3) WTO dispute proceedings.

National courts

After the Australian plain packaging legislation was adopted, but before it entered into effect, tobacco companies filed a lawsuit in 2011 at the High Court of Australia. The plaintiffs contended, among other things, that the plain packaging law should be overturned because it entailed “acquisition of property” – in essence a purported violation of property rights. The Australian High Court upheld the plain packaging law in 2012 in a 6-1 ruling.

Following the adoption of plain packaging laws in England and Ireland in 2015, tobacco companies filed lawsuits in British and Irish courts. These cases are ongoing; the British and Irish governments have indicated that they will defend the cases vigorously.

Uruguay has also instituted a number of robust tobacco control measures, including large graphic health warnings on cigarette packs, bans on misleading words like ‘low-tar’ and ‘light,’ and the limit of one line for the brand name. These measures are part of Uruguay’s efforts to implement the WHO’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), which it ratified in 2004.

Beginning in 2008, Abal Hermanos – the Uruguayan affiliate of tobacco giant Phillip Morris International (PMI) – and several other tobacco companies, filed lawsuits against Uruguay’s tobacco regulations. In 2009, Abal Hermanos filed a lawsuit at the Supreme Court of Uruguay, alleging, among other things, that its brands had been expropriated. Uruguay prevailed in the national cases.

BIT Tribunals

The so-called Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT) and Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) mechanisms are gaining attention in policy circles. Jarman writes that BITs “allow foreign investors to initiate investment disputes against governments that they believe have violated their rights.” The cases are then heard at a legal forum created for the individual investment dispute. The tribunal arbitrators are typically lawyers, one picked by the plaintiff, one picked by the defendant, and one picked by the arbitrators appointed by the parties.

BITs and ISDSs are unusual in that they give private companies the ability to sue governments using bilateral or multilateral governmental treaties, and to do so in a newly established legal forum with several options for a venue. According to leaked text, the draft Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPP), a regional trade agreement currently being negotiated, includes ISDS provisions.

Uruguay faces a BIT-based case. PMI used a 1988 BIT (ratified in 1991) between Uruguay and Switzerland to request an arbitration tribunal hearing at the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID). The BIT was ratified 13 years before Uruguay ratified the FCTC and 19 years before the PMI BIT-based action. PMI and its affiliates alleged, among other things, that the Uruguayan “80 per cent health warning coverage requirement unfairly limits Abal’s right to use its legally protected trademarks . . .” and caused “a deprivation of PMP’s [Phillip Morris Products] and Abal’s “intellectual property rights.”

The PMI v. Uruguay BIT case is not moving quickly. PMI appointed its arbitrator and Uruguay appointed its arbitrator. They were unable to agree, however, on the third arbitrator, who had to be appointed by the ICSID Secretary General. In 2013, the ICSID agreed that it had jurisdiction to hear the case. The case is expensive for a country of 3.4 million people with a gross domestic product (GDP) of only 57 billion US dollars; Uruguay has apparently received financial support from various sources to defend the case, including from American billionaire and former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg.

Similarly, using a 1993 Australia-Hong Kong BIT, a PMI subsidiary launched an action against Australia’s plain packaging law in 2011. PMI alleged that the plain packaging legislation contravened the Australia-Hong Kong BIT “in that they expropriate the investments, are unfair and inequitable, unreasonably impair the use of the investments, amount to a failure to afford full protection and security for the investments, and contravene obligations Australia has entered into with regard to investments of investors, specifically international trade obligations.” PMI also contended that plain packaging is a “technical regulation that is not necessary to fulfill the objective of protection of public health.” Three arbitrators have been appointed – one by PMI, one by Australia and one by the Permanent Court of Arbitration. The case is ongoing.

WTO dispute proceedings

Several countries have launched dispute proceedings against Australia for its plain packaging law at the WTO. The case is expensive both for the complainants and Australia. Jarman cites research indicating that the tobacco industry provided legal and financial support to the countries that lodged the dispute proceedings against Australia.

Ukraine, the first complainant in the WTO proceeding, alleged that the Australian plain packaging law is inconsistent with, among other things, various provisions of the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS Agreement). Several other countries later joined the WTO dispute and a panel was convened.

The action did not make contentions regarding human health and possible discrimination, but placed its hope in contending that stylish advertising on a cigarette pack is intellectual property and should be protected. In May 2015, Ukraine requested that the convened WTO panel suspend its proceedings “with a view to finding a mutually agreed solution.” In June 2015, the panel granted Ukraine’s request and suspended its work.

Forum shopping and bulk buying

Jarman writes that the aforementioned tobacco industry strategy is called ‘forum shopping’ and ‘bulk buying.’ She describes forum shopping – or ‘venue shopping’ – as “the practice of selecting the venue, such as an agency, committee, court, or arbitration body, most likely to provide you with a favourable result.” She describes ‘bulk buying’ as “using multiple forums at once to mediate conflicts over tobacco policy.”

The multiple legal actions against Australia and Uruguay have injected significant complexities and expenses into the adoption of public health regulations. Most likely, the actions have deterred or delayed other countries, especially under-resourced ones, from adopting similar public health laws.

Conclusion

In Australia, data shows that smoking rates have declined and illicit trade has not increased in the period since December 2012 when plain packaging entered into effect. The evidence reflects that plain packaging is working as intended – it is reducing tobacco consumption with no ill effects.

The Australian Border Force (formerly the Australian Customs and Border Protection Service), a WCO Member, has been reporting diminishment in the number of illicit tobacco seizures, one proxy for estimating the illicit trade in tobacco, while taxes have been increasing and plain packaging nears its three year anniversary.

There have been few, if any, examples of counterfeiting of Australian plain packs. One might conclude that the Australian plain packaging law is a technical regulation that is necessary to fulfill the objective of protecting public health and that there is credible evidence that it is reducing smoking prevalence.

More information

www.palgrave.com/