Implementing the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement will deliver huge dividends to the global economy

14 February 2016

By Coleman Nee and Robert Teh, World Trade Organization, Geneva, SwitzerlandBy the conclusion of the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) Tenth Ministerial Conference in Nairobi, Kenya in December 2015, a total of 63 WTO members had ratified the Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA), bringing the Organization closer to the threshold – two-thirds of its 162 members – necessary for the Agreement to come into force.

The TFA is designed to streamline, speed up and coordinate trade procedures across countries, which promises to lower trade costs globally and provide a significant, sustained boost to international trade, particularly in developing countries. The anticipated benefits from the TFA also include faster global economic growth and greater export diversification in implementing countries.

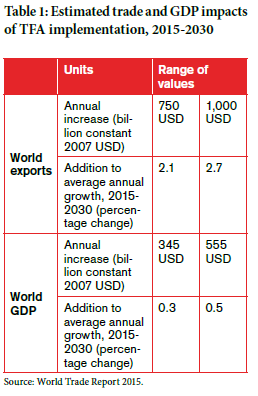

The 2015 World Trade Report, released on 26 October 2015 by the WTO, estimates that the TFA will increase world trade by between 750 billion and 1 trillion US dollars (USD) per year (possibly more under ideal circumstances, such as full implementation), and boost global gross domestic product (GDP) growth by an estimated 0.5% per annum.

Since the scale of potential benefits depends on the speed and extent of implementation, the TFA includes provisions to help developing countries reach full compliance. As the first multilateral trade agreement since the establishment of the WTO in 1995, the TFA also represents a major breakthrough.

Although mega-regional trade agreements, such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), have garnered more attention recently, the multilateral nature of the TFA means that its impact could ultimately be more far-reaching.

The TFA in context

In today’s interconnected global economy, the speed and ease with which goods cross borders matters for trade, at least as much as traditional trade obstacles such as tariffs and quantitative restrictions. Efficient trade procedures are particularly important in a world characterized by global supply chains, where production networks often require just-in-time delivery of essential inputs. It is possible for countries to unilaterally undertake trade facilitation reforms, so why is a multilateral agreement necessary?

Improvements in trade procedures benefit not only the reforming country but also its trade partners. However, trade facilitation reform often requires a country to invest resources. Governments behaving rationally will only spend on improvements up to the point where marginal benefits to the nation equal marginal costs, which means trade facilitation reform will be undersupplied globally. A multilateral agreement on trade facilitation would help countries realize opportunities for mutual gains, thereby leading to greater investments in efficient Customs procedures.

A multilateral agreement also proffers a solution to a persistent coordination problem. Common or similar procedures, such as those developed by the WCO, make it easier for traders to familiarize themselves with Customs procedures in different countries. A similar coordination role is foreseen in the way the Agreement facilitates the provision of technical assistance to developing countries, allowing these countries to undertake trade facilitation reforms that they could not achieve on their own. In addition, the legally binding nature of the TFA may help implementing governments overcome vested interests at home, in order to eliminate cumbersome border procedures.

The TFA’s provisions enhance certain aspects of existing WTO agreements while also creating a number of new disciplines. Specifically, the TFA contains measures related to the publication and availability of information, the opportunity to comment before entry into force of new/amended laws and regulations, advance rulings, appeal procedures, non-discrimination and transparency, fees and charges, release and clearance of goods, border agency cooperation, movement of goods, import/export/transit formalities, freedom of transit, and Customs cooperation.

Even though the implementation costs of the TFA are expected to be modest, they may still exceed the limited resources of many low-income developing countries. To address this issue, the Agreement includes extensive and innovative ‘special and differential treatment’ (S&D) provisions that allow developing countries to tailor the scope and timing of implementation to their particular circumstances.

At the same time, the TFA provides for technical assistance for developing countries from donor countries and organizations, in order to ensure full implementation. This assistance will be coordinated through the recently-inaugurated Trade Facilitation Agreement Facility, which is intended to act as a clearinghouse for information and a matchmaker of last resort between aid donors and partner countries (see www.wto.org/english/news_e/news14_e/fac_22jul14_e.htm).

In contrast to the TFA, Regional Trade Agreements (RTAs) that deal with trade facilitation generally do not include S&D provisions and aid for implementation. These omissions reduce the likelihood of trade facilitation measures in RTAs being implemented in poorer countries, where they are arguably most needed. The strength of WTO enforcement and dispute settlement mechanisms also distinguishes the TFA from other agreements that touch on trade facilitation. However, more ambitious RTAs could serve as a complement to the TFA.

Expected economic impact of the TFA

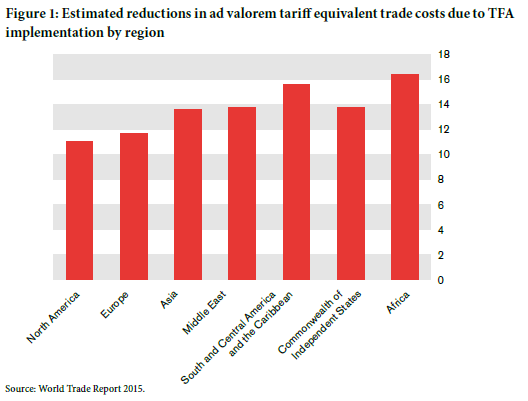

The trade costs that the TFA is designed to address are large, and differ markedly across regions and groups of countries. These costs are equivalent to an ad valorem tariff of around 170% for a typical developed country, and 219% for a typical developing country. Inefficient trade procedures appear to make up a significant part of these costs, which the TFA would reduce by more than 14% on average (see Figure 1).

Inefficient trade procedures result in importers paying more for traded goods, and exporters receiving less in exchange for their goods. However, when a country improves its trade procedures so that trade costs are reduced to zero, this price wedge vanishes. As a result, consumers in importing countries benefit from lower prices, and exporters receive higher prices for their output. Trade facilitation contributes to a marked improvement in the income of both importers and exporters, improving their terms of trade and creating a ‘win-win’ situation.

The 2015 World Trade Report relies on a Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) simulation model to estimate export and GDP gains from the TFA. As noted above, expected trade gains range from 750 billion to over 1 trillion USD per year, with larger values corresponding to faster and fuller implementation (see Table 1). Other estimation techniques – so called ‘gravity models’ – yield even larger estimates of the expected gains, assuming full implementation, which suggests that the CGE estimates may be somewhat conservative.

Implementing the TFA would not only provide a badly-needed lift to the global economy in the short term, it would also raise its growth trajectory over the medium-to-long term. If fully implemented, the TFA could add up to 2.7% a year to world export growth and 0.5% per year to world GDP growth, over the 2015-2030 period.

Implementing the TFA would not only provide a badly-needed lift to the global economy in the short term, it would also raise its growth trajectory over the medium-to-long term. If fully implemented, the TFA could add up to 2.7% a year to world export growth and 0.5% per year to world GDP growth, over the 2015-2030 period.

Beyond simply increasing trade and output, the TFA would also create additional benefits that include:

- Export diversification – The WTO expects developing and least developed countries (LDCs) to reap significant export diversification gains from the TFA, increasing the number of products they export per destination by 36%. They would also increase the number of export destinations per product by nearly 60% after implementation. Export diversification would help insulate developing countries and LDCs from adverse economic shocks affecting specific sectors or destination markets;

- Faster delivery of time-sensitive goods – Delivery times are crucial for the effective operation of global supply chains, and also for trade in perishable agricultural goods. The TFA is expected to boost trade in these products by reducing the time needed to export, and by increasing predictability of delivery times;

- Greater participation of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in trade – Burdensome trade procedures and Customs regulations are often cited as major obstacles to exports by SMEs. This may be because larger firms, and especially multinationals, are better equipped to navigate complex regulatory environments. Drawing on World Bank Enterprise Surveys, the report finds evidence that SMEs are far more likely to export and to increase their export shares than large firms, when Customs clearance times are reduced;

- More foreign direct investment (FDI) – In the case of small economies, trade facilitation not only leads to more trade, but also increases FDI inflows. This is confirmed by empirical analysis showing a positive and statistically significant link between trade facilitation and inward FDI flows, using a dataset covering 141 countries over a 10-year period, namely 2004-2013;

- More efficient revenue collection – Trade facilitation reforms help boost government revenues by increasing trade flows, thereby expanding the tax base and increasing tax collection efficiency for any given level of imports;

- Reduced corruption – The incentives to engage in fraudulent practices at the border are greater when more time is needed to complete Customs procedures. Since trade facilitation is expected to shorten waiting times, it creates an important avenue for reducing incidences of trade-related corruption.

Implementation challenges

The costs associated with improved trade facilitation include diagnostic and needs-assessment costs, regulatory and legislative costs, institutional and organizational costs, human resources and training costs, equipment and infrastructure costs, awareness-raising costs, the costs of addressing political resistance, and operational/maintenance costs.

For developing countries, some of these costs will be offset by aid from donor countries and technical assistance from institutions like the WCO, but they are not the only, or even the main obstacles to implementation. Based on experience gained from existing trade facilitation efforts, successful reform will require a sense of national ownership and broad stakeholder participation, including the private sector. Other keys to success include mobilization of material and financial resources, and correct sequencing of reforms.

WTO members are steadily ratifying the TFA. When the Agreement is finally in place, it promises to make a strong contribution to the revitalization of international trade at a time when such rejuvenation is badly needed. Once it is in force, it will be essential to monitor the implementation of the TFA to gauge its progress, identify problems, and assess how well the S&D provisions of the Agreement are working.

The WTO, together with other organizations, such as the WCO and regional development banks, should invest more resources in the collection of data, particularly with regard to implementation costs, the improvement of existing indicators and analytic tools, and the development of new ones, so as to better monitor and evaluate the implementation of the TFA.

The full report can be downloaded from the WTO’s website, which also contains a wealth of detailed information on the TFA and its provisions.

More information

www.wto.org/english/res_e/publications_e/wtr15_e.htm