The EU cracks down on e-waste crime

14 February 2016

By Juha Hintsa , Cross-border Research Association and Sangeeta Mohanty, Cross-border Research AssociationCountering the illegal trade in waste in electrical and electronic equipment, also known as e-waste or by the acronym WEEE, is a challenging, and actual topic for governments, industries, and academics alike. Human health and safety issues, environmental protection concerns, and the economic aspects related to the re-use of raw material, all call for increased attention and enhanced enforcement in the context of e-waste trade, transport, and treatment. To assist government policymakers and enforcement bodies, as well as WEEE-related industries, in countering illicit activities around e-waste, the European Commission decided to launch, in 2013, the Countering WEEE Illegal Trade (CWIT) project. This article outlines the recommendations developed by a group of experienced professionals who participated in the project.

WEEE volumes

Estimating the total volumes of e-waste produced and the size of the illicit market was one of the first tasks undertaken by the experts who participated in the CWIT project. They found that the total amount of WEEE generated in 2012 by the 28 European Union (EU) Member States plus Norway and Switzerland was 9.45 million metric tons. Of these, 3.3 million tons were reported by EU Member States as having been collected and recycled, 0.75 million tons were estimated to have ended up in the waste bin, and 2.2 million tons of mainly steel-dominated consumer appliances were collected and processed under non-compliant and sub-standard conditions with other metal scrap.

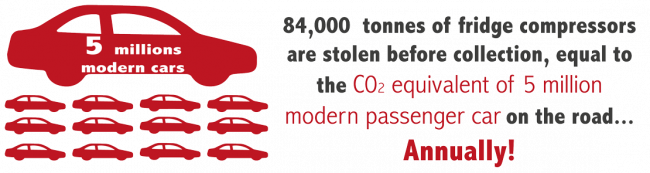

Based on a market survey, it is estimated that 750,000 tons of valuable parts do not make it to the official collection points. They include significant amounts of refrigerator compressors (84,000 tons out of 300,000 are scavenged; roughly equal to the annual CO2 emissions of five million cars!), and cable and information technology (IT) components (180,000 tons), all of which are commonly exported to Asia. In total, 1.5 million tons leave the EU annually: 200,000 tons are documented as used electrical and electronic equipment (UEEE) exports, since it is legal to export functioning UEEE; and the remaining 1.3 million tons are also predominantly UEEE, but are frequently mixed with WEEE before being exported.

Based on a market survey, it is estimated that 750,000 tons of valuable parts do not make it to the official collection points. They include significant amounts of refrigerator compressors (84,000 tons out of 300,000 are scavenged; roughly equal to the annual CO2 emissions of five million cars!), and cable and information technology (IT) components (180,000 tons), all of which are commonly exported to Asia. In total, 1.5 million tons leave the EU annually: 200,000 tons are documented as used electrical and electronic equipment (UEEE) exports, since it is legal to export functioning UEEE; and the remaining 1.3 million tons are also predominantly UEEE, but are frequently mixed with WEEE before being exported.

Weaknesses in legislation and enforcement

The group then looked into the existing gaps in legislation and enforcement systems. Several loopholes created enough leeway for criminal operators to circumvent controls, and in case of detection, to get away with minimum penalties. Some of the major gaps are mentioned below:

- Ambiguities in the definition and classification of WEEE in international legislation have led to discrepancies in classification among EU Member States, and made distinction between waste and non-waste particularly difficult for Customs officers;

- Shortage of human capacity among port authorities to physically inspect all containers dispatched from Europe – as an indication, at a major European port about 20 containers of WEEE are packed each week (approximately 1000 containers per year), and the port authority only manages to inspect about 10 containers a year;

- No unified information system among national and international agencies to enable targeted inspections;

- Lack of specific training for Customs inspectors and police on WEEE issues;

- Lack of technical equipment to assess the hazardous nature of WEEE shipments;

- Cumbersome process of collecting evidence against the perpetrator, and proving the hazardous nature of the shipment;

- Low penalties imposed in many countries that do not act as a deterrent to crime;

- Large discrepancies in the penalty levels and systems across EU Member States that cause offenders to shift their activities to less stringent jurisdictions;

- Limited number of prosecutions carried out.

A set of recommendations to improve the situation were provided to policymakers and regulators, the law enforcement community (Customs, police and environmental administrations), and the WEEE treatment and electronic industry, under four overarching themes.

Recommendations under theme 1: collect more, prevent leakage, and monitor performance

Educate consumers

A lack of public awareness on WEEE issues is related to bad disposal practices. Concrete improvement measures include rolling out communication campaigns for end users to raise awareness around the proper disposal of WEEE, running of attitudinal surveys to investigate motivations and potential incentives for users, and assessing the possibility of running law enforcement campaigns for end users to tackle fly tipping and improper kerbside disposal of WEEE.

Improve collection

In many EU countries, collection facilities are too few, insufficiently accessible, or exposed to thefts. Improvement suggestions include increasing the number of collection points, enhancing the visibility and accessibility of existing ones, improving security at collection points, and introducing a ban on cash transactions to reduce the profitability of unlawful activities and the viability of cash transfers related to WEEE illegal trade.

In many EU countries, collection facilities are too few, insufficiently accessible, or exposed to thefts. Improvement suggestions include increasing the number of collection points, enhancing the visibility and accessibility of existing ones, improving security at collection points, and introducing a ban on cash transactions to reduce the profitability of unlawful activities and the viability of cash transfers related to WEEE illegal trade.

Improve national monitoring

Reliable quantitative data is crucial to determine progress towards achieving WEEE collection targets, or the amounts of e-waste that end up outside the official WEEE chain. The proposed action steps include improving local monitoring and benchmarking in all official collection points, improving access to information by creating specific lists for WEEE-related companies, developing a national WEEE monitoring strategy, and improving current methods for calculating e-waste indicators that form the basis for national mass balance calculations.

Reporting by all actors

EU countries face the common problem of non-reporting, incorrect reporting, and underreporting of collected and treated WEEE amounts by compliance schemes, producers, and recyclers of WEEE due to certain deficiencies in the system and incompatible codifications. The suggested improvement measures include establishing reporting obligations for all actors collecting WEEE products, using an unequivocal description of WEEE that is understood by all actors that have to report, use of the same codes or use of codes that allow comparability in reporting processes, and establishing a control system of data collected that will assess the reliability of the data reported.

Recommendations under theme 2: trading, treatment, and the economic drivers

Improve treatment

A core problem is the lack of quality standards in WEEE treatment. A specific challenge is that many of the recycling requirements do not positively impact the legitimate industry over non-regulated players. As a consequence, unqualified treatment operators put responsible recyclers at a disadvantage. Initiatives must, therefore, be designed to support the legitimate treatment industry through the implementation of (mandatory) WEEE standards, improving reporting on treatment within and outside Europe, making de-pollution more economically rewarding, and improving treatment in developing countries.

Improve reuse

There is an urgent need for clarity on the implementation of the various guidelines, and to develop measures on how to discriminate between shipments for proper reuse, and those shipments of mixed quality with too many appliances of low, or no remaining, useful life. Low quality shipments can be reduced by using harmonized definitions for reuse and refurbishment, developing uniform reuse standards and guidelines, providing training and capacity building for the refurbishment/reuse industry, and establishing ‘green’ reuse channels and approved reuse centres, under the precondition that sufficient upstream inspections take place, and that the various guidelines for testing and packaging are fully implemented.

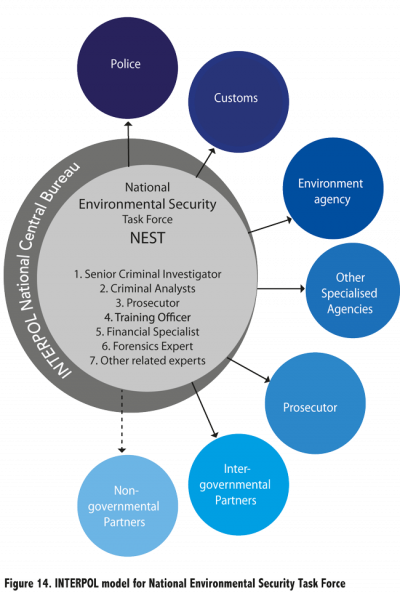

National WEEE networks

Poor cooperation across authorities – including Customs, police, prosecuting, and other specialised agencies – results in difficulties in the identification of environmental crimes, and in securing evidence required for successful prosecution. Two actions were recommended: enhancing multi-stakeholder networks by involving different types of stakeholders in programmes aimed at tackling the WEEE illegal trade; and establishing National Environmental Security Taskforces (NESTs) to ensure a coordinated multi-agency response.

Smarter inspections and investigations

According to the European Commission, only 2% of all the world’s maritime containers are physically inspected by Customs authorities, and of the 2%, only a small number of inspections are done for WEEE shipments. As regards investigation procedures, there seems to be no general methodology for investigating environmental crimes, and the numbers of investigated cases are limited. These issues can be appropriately handled by ensuring more effective and successful inspections through targeted border inspections, conducting intelligence-led risk assessments and improving detection techniques, improving WEEE investigations through better investigative procedures, and conducting more and smarter upstream inspections of facilities in order to prevent illegal activities moving downstream.

Recommendations under theme 3: robust and uniform legal framework, and implementation

Improve waste codifications

The suggested actions to improve the classification of WEEE are to develop import/export codes for WEEE and second-hand commodities in order to differentiate between new and used ones, have a consistent interpretation of waste versus non-waste, encourage collaboration and agreement between stakeholders to progress towards more harmonized WEEE classifications and definitions, and develop compatibility tables to allow for conversion between codification systems.

Produce and maintain consistent guidelines

Various definitions and guidelines related to WEEE exist at national, regional, and international levels. These issues can be addressed by improving the availability, awareness and understanding of existing guidelines, providing sufficient support and training to authorities, developing certification in the use of guidelines, and campaigning for official endorsement of guidelines by relevant authorities.

Train authorities

Insufficient guidance and training often prevent Customs and environmental officers from proving the illegal nature of a shipment. Proposed actions include the establishment of centres of excellence and/or an EU waste agency, providing specialized training for personnel (Customs officers, environmental inspectors, etc.), facilitating cross-border inter-agency capacity training between stakeholders involved in both the export and import of WEEE, and the establishment of public-private partnership schemes (between law enforcement authorities and the WEEE industry).

Harmonize and enhance penalty systems

Participation in WEEE illegal activities does not appear risky to offenders due to the low probability of being prosecuted and sentenced, and there are large discrepancies in the penalty systems and levels for the illegal trade in e-waste across the EU. The proposed actions include assessing if sanctions are proportionate and dissuasive, increasing penalty levels for natural persons who are company representatives, harmonizing offences related to WEEE crimes at the EU level (wording, definitions, and severity), harmonizing penalty types at the EU level, and providing specific penalties to tackle organized crime involvement in WEEE illegal activities.

Recommendations under theme 4: best practices in enforcement and prosecution

Enhance information management systems

A lack of information exchange, and a lack of statistics about illegal WEEE activities have been reported both at national and international levels. Discrepancies have been identified in data reported by different authorities in the same country. Suggested actions to counter the situation include putting in place formalized agreements for the exchange of information between law enforcement, judicial authorities, and the WEEE industry, establishing an Operational Intelligence Management System (OIMS) that enables the secure input, management, development, analysis, and dissemination of intelligence and critical information especially during the planning of law enforcement actions, using intelligence to prioritize and direct resources towards the operations and policies that will be most effective in combating crime, and building a national intelligence model to implement a full set of best practices in intelligence-led policing and law enforcement.

Invest in capacity building for LEAs

A common bottleneck for poor implementation in most countries is limited resources and capacity. It is therefore deemed necessary to provide more human resources and equipment, facilitate international cooperation, including the exchange of Customs inspectors, across competent authorities, conduct a risk assessment and allocate staff according to the expected risks identified, and strengthen the capacity of existing networks (such as EUROPOL and INTERPOL), as an effective and cost-efficient capacity building initiative, instead of creating new networks.

Improve international WEEE networks

To strengthen international cooperation in law enforcement, two actions are proposed: first, encourage the participation of relevant agencies involved in international waste operations and enforcement actions to bring together neighbouring countries to target waste and WEEE trade/operations; and second, create an EU waste implementation agency to support Member States through training, and to act as a platform for the exchange of knowledge and best practices.

Enhance prosecution and sentencing capabilities

Environmental crime seems to be an under-sentenced area. There appears to be a major gap between the number of WEEE violations and the number of successfully prosecuted cases across Europe. This can be addressed by improving the capacity and resources of prosecutors and judges, and enhancing communication and cooperation among prosecutors and judicial authorities, in order to establish a database of information, contact points, and joint investigation teams. Increasing the role of EU and international networks, such as EUROJUST (an EU agency dealing with judicial cooperation in criminal matters), is considered another positive step.

Roadmap

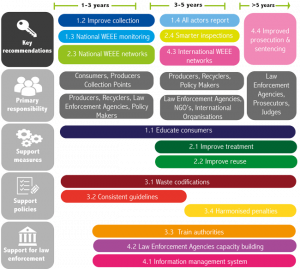

These recommendations are not standalone, but rather mutually dependent and impact one another. Hence, the final step in the project was to prioritize and structure the recommendations, and to develop a roadmap illustrating the time needed for implementation, as well as the actors that are primarily involved. This roadmap is reproduced below.

More information

www.cwitproject.eu