Geospatial data at the service of Niger Customs

24 February 2022

By Dan Bouga Boukari, Head of the Data Analysis and Reform Unit, Niger Customs, Nicolas Saporiti, Geo212 Director, and Romane Delteil, geographic analystIn the June 2019 issue of WCO News,[1] the WCO Secretariat encouraged Customs to examine the use of geodata for more effective border management. In Niger, the Customs service recently financed a study into the use of satellite imagery to analyse cross-border trade flows. This paper presents the information collected and explains how it will be used to reorganize operational services and provide efficient links within the territory.

The borders of Niger

Niger is a landlocked country that shares land borders with seven countries. Goods exported, imported and in transit are transported by land over a vast territory. In addition to managing legal trade, the mandate of the Customs service is also to combat a variety of illegal trafficking, particularly drugs, gold and humans,. The territory’s size and border porosity represent a considerable challenge.

This is compounded by increasing insecurity along these borders. For almost a decade, the country has been countering attacks by the Boko Haram armed group around Lake Chad and by other terrorist groups – mainly affiliated to Al Qaeda and Islamic State – in the Liptako-Gourma region on the Mali-Burkina Faso border. The latter is also a stage for criminal activity, banditry and community conflicts.

While the Customs service has a physical presence on the ground, it is sometimes limited and fails to seize all trade flows or to optimize the organization of services and their operations. In response to these constraints, it was decided to carry out a geospatial study using, in particular, satellite imaging to list and map the main centres of cross-border trade and signs of developing activity.

Geospatial expertise to analyse flows

The study was supported by the World Bank and was entrusted to Geo212, a geo- intelligence and imagery consultancy company. The analysts started from the assumption that flows of goods generate enrichment, which leaves traces on the ground. These “markers” include, for example, urban development, the enlargement or creation of markets and storage facilities, the creation of new transit routes or increased trafficking flows on known or alternative routes.

The study focused on two aspects of the territory :

- trade centres, a general term that includes towns and transit zones; and

- the road transport network (since road transport is the most important means of transport in Niger).

The analysis required several essential skills:

- spatial imagery skills, involving a knowledge of the provision of the data (costs, frequency of acquisition, spatial resolution, etc.);

- photo interpretation skills (object detection and identification, time observation);

- geographic skills, involving a knowledge of how to connect the results of observations to a context (political, security, economic) and to a geographic situation, whether local or more global; and

- open source skills (mapping and statistical portals, press articles, reference works and other documentation), involving a knowledge of these sources and the ability to classify, manipulate and interlink them.

The combined use of this varied expertise makes it possible to produce useful and accurate geographic information, i.e. information that reflects the reality of the terrain. This makes it possible to construct original geographic analyses which are essential for taking decisions in response to the specific needs of Customs officers.

The analytical method

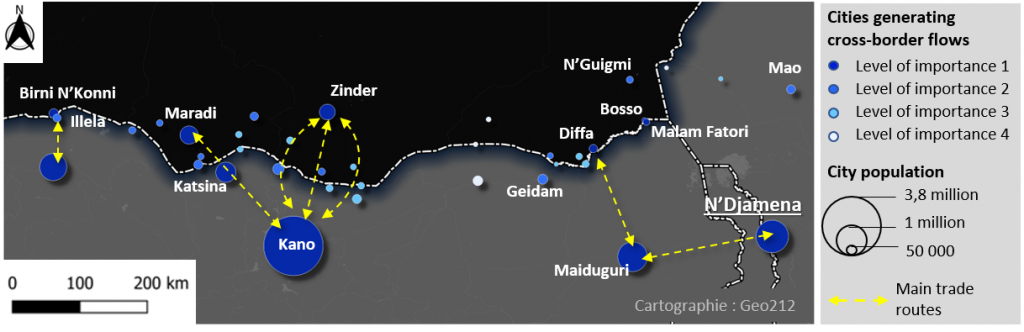

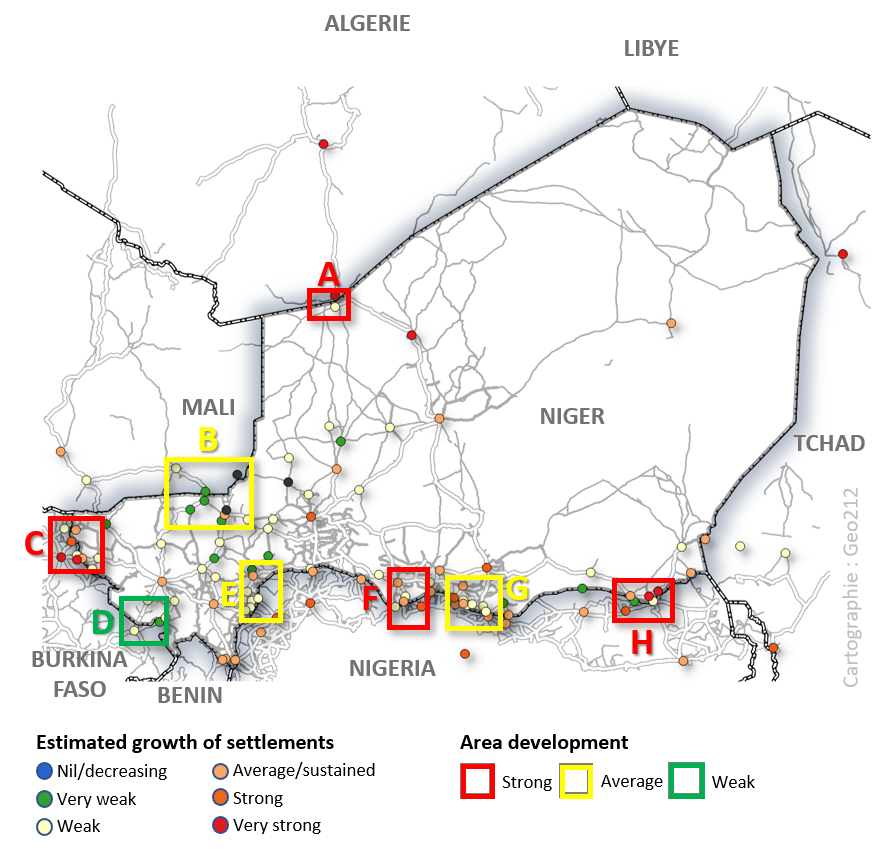

A general analysis of the entire territory of Niger was first carried out to identify the principal cross-border trade centres in Niger and in neighbouring countries, and the routes that link them. A total of 71 towns involved in cross-border trade in Niger were selected, characterized and related to each other (Figure 1).

Figure 1 : Example of links, Niger/Nigeria border area and main trade routes

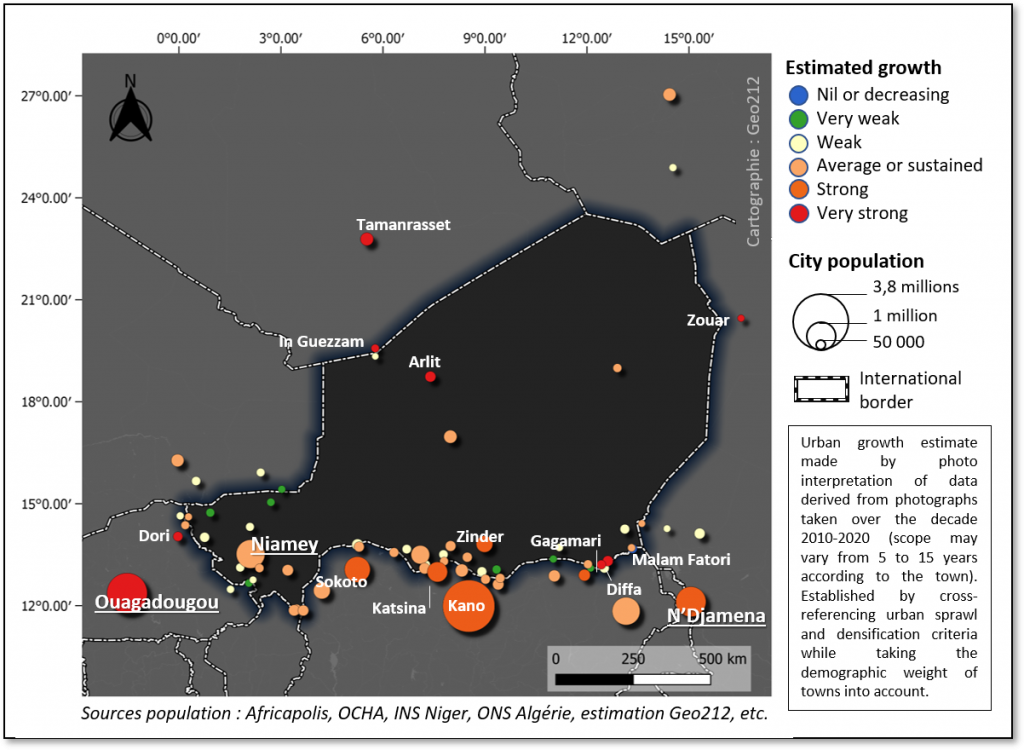

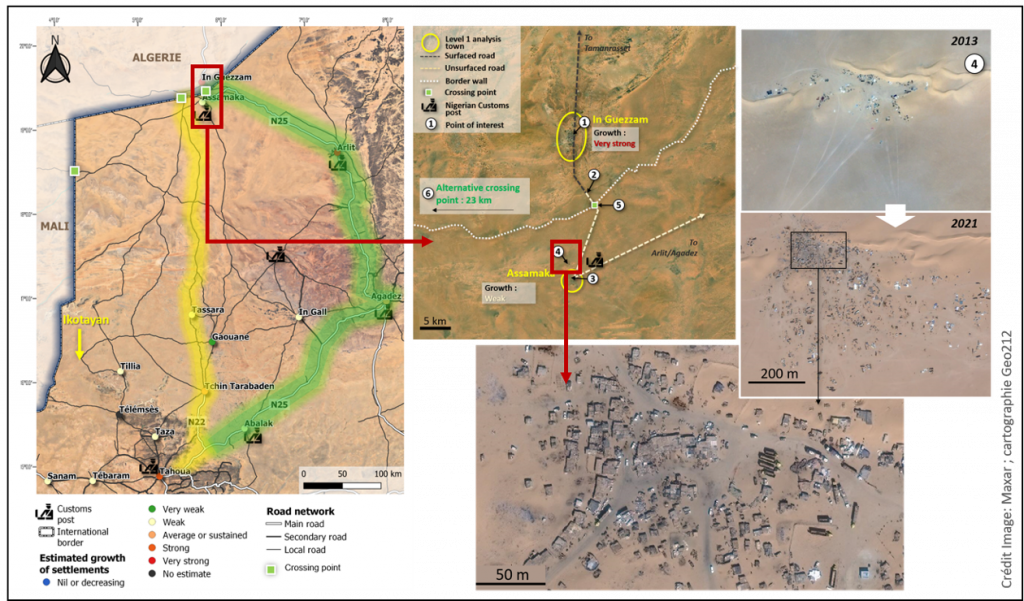

This preliminary analysis then made it possible to present a mapping of the estimated growth of these towns over the previous 10 years (Figure 2) to identify the most dynamic border areas.

Figure 2 : Estimated growth of towns involved over a period equivalent to the decade of 2010-2020

A total of eight areas of various sizes likely to have active cross-border corridors and two known transnational corridors were then identified for closer examination. The contribution of the Customs services was essential during this stage. Dialogue between Customs staff and Geo212 analysts made it possible to adapt the methodology very closely to operational needs. The analysts stressed the topographic and anthropomorphic characteristics of the border of each of the eight zones, identified the main and alternative crossing points and listed particular points of interest. The known corridors were then examined to highlight, alongside the official routes, the alternative routes likely to be used within Niger itself and for crossing borders.

This second analysis was based on very high resolution (submetric) satellite imagery which made it possible to observe the development of locations in detail (growth of small settlements, structuring within cities, appearance of storage facilities or border posts, etc.). The analysts were able to link some changes in the security context (militarization of an area, appearance of camps, destruction of villages, etc.) and produce a global vision of the cross-border dynamics of each zone.

Figure 3 : Multiscale analysis of a cross-border transit zone, from the national corridor to the Assamaka crossing point to the Niger/Algeria border

Figure 4 : Cartographic overview of the results of the analysis of cross-border areas

Reusable results by Customs

All the observations are detailed and summarized in a very well-illustrated report that has been submitted to the Niger authorities. Moreover, the objects of interest and border crossing points identified have been compiled in a database given to the Customs service. The latter can now cross-reference their own data with the information provided. This will allow Customs to build new decision-making supports to guide the reorganization of operational services and ensure coverage which is more closely adapted to the territory.

Reflections have focused on the following points:

- creation of new Customs posts;

- removal or relocation of some Customs units;

- raising of the baseline proficiency of some Customs offices; and

- greater allocation of equipment for some operational units.

Geospatial data and border surveillance

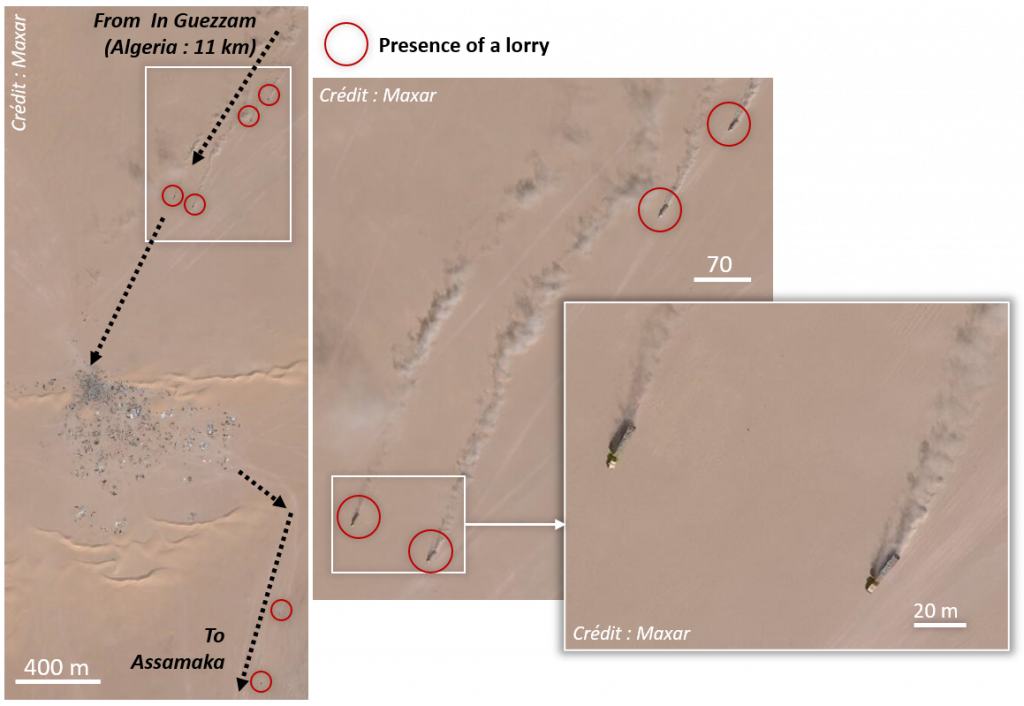

This study has demonstrated the utility of current earth observation tools in analysing border dynamics. These tools facilitate highly detailed observations in areas which are difficult to access for topographic or security reasons. They also allow temporal comparisons, and development analysis.

Future filed changes could therefore be followed setting up a monitoring service allowing regular updating geographic data. It would also be possible to identify which routes are actively used in some border areas: the number of lorries listed on the images and the multiplication of obvious traces are indicative of recent regular movement (Figure 5). These observations will be supported by future satellite constellations, that will make daily or even multi-day analyses possible.

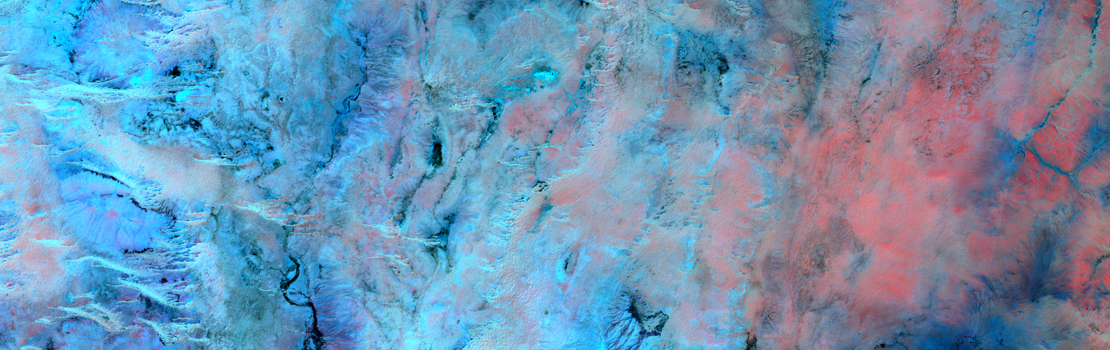

Figure 5 : High resolution image of a very busy transit zone on the Algeria/Niger border, analysed in the study

More broadly, this work has highlighted the relevance of geospatial analysis for Customs, and there is no doubt that the work carried out with Niger, under the auspices of the World Bank, can be reproduced in other countries.

More information

www.geo212.fr

nicolas.saporiti@geo212.fr