Customs, cultural goods and data

14 February 2016

By María Esther Portela Vázquez, Researcher, Cultural Heritage International ProtectionFor years, Customs administrations have been able to transform the raw information they collect on drugs, weapons, and humans trafficking into data which could be analysed to provide meaningful insights in the fight against these illegal activities. However, when it comes to the illicit trade in cultural goods, progress achieved in data collection is some way behind that obtained in other transnational crime areas. This article identifies the data which needs to be collected, stored and analysed following the seizure of cultural goods, and how it can be used to enhance the protection of cultural heritage.

Experts estimate that the illicit trade in cultural goods is amongst the types of transnational crime generating the most revenue. Our past is being looted, stolen, and illicitly traded, but to what extent? That is an unresolved question. Finding an answer is not easy because the data that could be used to estimate the scale of this type of crime does not seem available.

In fact, anyone asking about data is likely to receive contradictory answers. Some will tell you that there is data, and others that data on the illicit trade in cultural goods cannot be collated.

The truth is that there are important and valuable databases on stolen artworks, such as the INTERPOL Stolen Works of Art database, and initiatives such as Project PSYCHE (Protection System for Cultural Heritage), which aims to facilitate data collection and further increase the content of the INTERPOL database.

These tools are useful for anyone looking for specific data on a reported stolen artwork or wishing to report a theft of an artwork and information about the stolen items, such as a precise description of the missing artwork, photographs or other relevant data.

Besides those tools, many developed countries have their own enforcement databases which include information about seizures and investigations, and researchers looking for specific data can request to have access to this information. This being said, why is there still a belief among practitioners in the field that no quantitative data on the illicit trade in cultural goods is available?

Lack of data: myth or reality?

Several explanations can be put forward.

First, most data is not made public. Databases are normally owned by enforcement agencies or governments and, for security reasons, access is restricted despite the fact that the illicit trade in cultural goods is a problem that not only interests enforcement agencies, but also many protagonists involved in this field, such as archaeologists, anthropologists, antique dealers, collectors, tribes, museums, and lawyers among others. Each of them has its own need for data.

Second, there might be a lack of data. Convincing administrations to share data is not always easy. International organizations dealing with the protection of cultural goods can find themselves in a situation where not enough data is available for a proper analysis.

Third, there might be a lack of efforts to share data. Each country has its own constraints and priorities. Lack of resources and awareness, low priority ranking of this type of crime compared to terrorism or other transnational crime, such as drugs or human trafficking, can explain why countries are not all collecting and transmitting data on the smuggling of cultural goods.

Fourth, there might be a lack of quality in the data, including low levels of detail. We are living in a time that has been defined as a ‘time of datification’, i.e. processes or activities that were previously invisible are turned into data. We buy tickets and books and make reservations online, and within minutes receive targeted adverts based on our searches. Our actions are registered and automatically analysed.

Although existing technology allows for the gathering, storing and analysing of big quantities of data, databases used to store data on the illicit trade in cultural goods is sometimes not formatted to store all possible sorts of data, or requests a level of information that is too general, with critical information being left out. Other times, databases are more complete, but do not allow for information to be cross-referenced in order to exploit the full potential that the data offers.

For instance, can a correlation between the place of theft, the kind of objects seized and the location where the seizure was made be established? And between the types of objects, their country of origin and the specific border where the seizure took place?

Fifth, it could be due to the type of raw information that is stored in existing databases, which reflects the intended use of the data. INTERPOL states that “National statistics are often based on the circumstances of the theft rather than the type of object stolen.”

Cultural goods are very specific: they are heterogeneous and have their own peculiarities. An Egyptian sarcophagus, an ancient funerary mask or a pre-Columbian archaeological object could be considered cultural goods, but so could an AK-47 if it belonged to a national leader or was linked to a historical event.

Raw information regarding the type of object usually exists and is used by enforcement agencies to search for missing objects or to report seized objects, but it is frequently stored using descriptive fields rather than pre-defined ones. This is probably the best way to store information if it is to be used by enforcement services, but not if the information is to be quantified.

For instance, reporting that the ‘Codex Calixtinus’ was stolen from the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela in Spain, with a full description of its contents, dimensions and characteristics, is not the same thing as breaking down the information for easy analysis and quantification as follows:

- Number of items = 1;

- Type of object = manuscript, old books or documents;

- Place of theft = museum, monument or similar institution;

- Country of origin = Spain;

- Age = between 1100 and 1200 A.D.

Collected Customs information: how can it help?

Customs administrations collect and store an extraordinary amount of raw information that has huge potential to enhance the fight against the illegal trade in cultural goods. Information gathered when a cultural good is seized can be transformed into data if procedures and certain criteria are established.

For instance, let us imagine that Customs at JFK Airport in the United States (US) seizes a pre-Columbian artefact hidden in the suitcase of a New York-based antiquities dealer, and that although the object’s origin is unknown, it is known that the man was coming from Guatemala. This raw information can be broken down into the following data:

- Type of object = archaeological object;

- Number of objects = 1;

- Country where seizure was carried out = US;

- State = New York;

- Border = East Coast;

- Location at the moment of seizure = airport;

- Age of object = before 1522;

- Type of subject = antiquities dealer

- Place of origin = unknown;

- Date of seizure = 5 January 2016;

- Export country = Guatemala;

- Type of entry = non declared, etc.

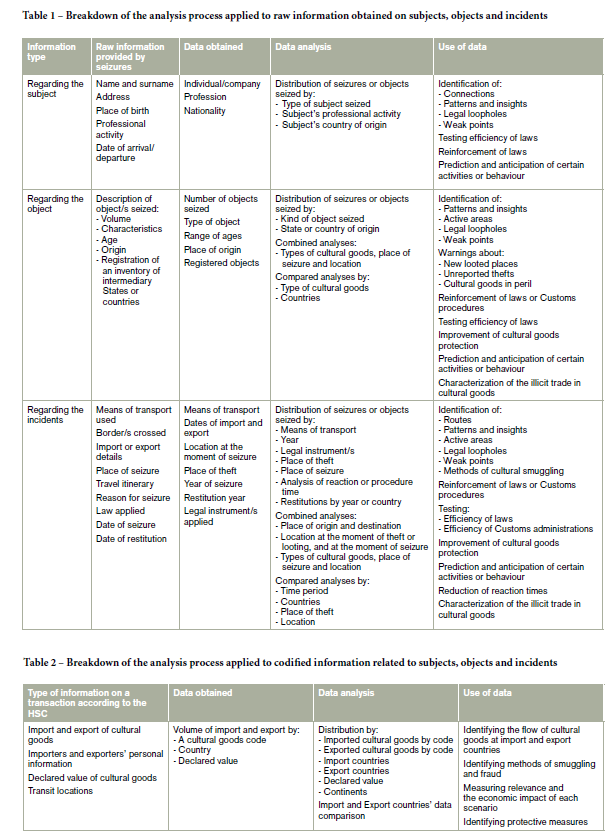

Information obtained following a seizure could be divided into three categories: subjects (individuals or companies); objects; and incidents. Raw information regarding subjects can be useful both before and after being codified and categorized. The advantage of post-codified data is that it is not protected by law, as it is broken down and does not refer to specific individuals but categories which makes it shareable.

For instance, the profession of the subject could be relevant information if it is established that certain professionals or economic activities are the most common kind of subject involved in seizures of cultural goods.

With regards to the smuggling of cultural goods, information related to objects is as important as information about the subjects due to the singularity and relevance of the objects seized. Most of them are unique and irreplaceable. Data related to objects can help identify patterns and trends.

For example, if a large number of ancient archaeological objects of Middle Eastern origin are being seized in more than one European country, it could reveal that there are attempts to bring antiquities from conflict areas onto the market.

Information derived from the analysis of data collected from seizure information would also enable the efficiency of the laws enacted to protect cultural goods to be tested. For example, cultural objects should appear on an inventory if they are stolen from museums, monuments or similar institutions.

But above all, this data could sometimes help highlight the very existence of an object and/or its theft. The existence of certain objects, such as those looted from unknown sites, remains in itself a mystery until these objects are detected at a country’s point of entry, or on its markets.

When a substantial number of the same kind of archaeological objects are being seized and those objects are from an unknown origin but with similar characteristics to other identified objects, it could suggest that a new site has been discovered and looted. The same is true for thefts – the disappearance of a cultural object in a library, for example, may go unnoticed until the object itself is found during a Customs check.

Data related to incidents can be useful in identifying smuggling patterns and trends, as well as smugglers’ behaviour. Certain aspects, such as the means of transport used, the chosen border, and the place where cultural goods were hidden or the period or frequency of border crossings can give some clues to better target controls.

Other information, such as the date of import and export, can be crucial too. A specific archaeological object, for example, could be protected by law depending on the date it was exported from its country of origin and/or the date it was imported into another country.

Harmonized System (HS) Code: what can this Customs tool do?

The other type of information that Customs administrations collect is the HS code of the goods seized – another important source of information. Works of art, collector’s pieces and antiques are found in Chapter 97 of the HS nomenclature. Classifying cultural goods according to the HS is especially important because it allows Customs administrations to shed some light on three different scenarios, and on the type of fraud involved if the transaction is found to be fraudulent: cultural goods that have been declared under Chapter 97 codes; cultural goods that have been declared with other codes; and undeclared cultural goods.

HS code statistics have another important role to play in the fight against the smuggling of cultural goods. As information on the illicit trade in cultural goods is rather fragmented, any researcher would find it helpful if supplementary raw information could be grouped. For example, for each type of cultural goods seized, the number and/or value of the goods according to the HS code under which they were declared, whether they were correctly classified or not, and similar statistics for goods that have been detected but not declared. This information could be complemented with other data collected, such as the country of origin, the type of location where the seizure occurred (airport, auction house, gallery, museum, private residence, etc.), and the border where it took place. The level of detail could even be higher, and could include the laws which were infringed, the real value of the seized items, etc.

Information-sharing: critical to fighting crime

One has to realize that the pieces of raw information stored by Customs can be extremely useful. The databases mentioned at the beginning of this article provide crucial information, but the illicit trade in cultural goods is a global phenomenon which transcends borders, and there is a clear need to collect more valuable and usable data, and to share it at a global level.

Some Customs administrations have made an effort to create safe virtual spaces where information can be shared. The WCO Customs Enforcement Network (CEN), for instance, is one of them. It is simple and user-friendly, and this makes it easy for Customs administrations around the world to report their data. In addition, the information contained in the CEN could provide a better understanding of the phenomenon, even if it is only partial.

Conclusion

One has to bear in mind that databases are not useful without a representative quantity of entries, and well-defined fields of information. Obtaining and collecting reliable data on the trade in cultural goods should be considered as an unavoidable necessity. After all, it is considered perfectly normal in other disciplines.

More information

eportelav@gmail.com