Cameras: one way of making traffic controls more efficient

18 October 2023

By Cédric Orgeret, French Customs and Thomas Cantens, Research Unit within the Office of the Secretary General at the WCOBetween 2021 and 2023, French Customs trialled the use of cameras in covert surveillance systems on the roads. Positioned discreetly on the ground and connected to a 4G system, they allow Customs officers to detect suspicious movements remotely. As mobile devices mounted onto a helicopter or drone, they facilitate wider-ranging surveillance beyond the confines of checkpoints. This article presents details of the trials conducted by French Customs along with the lessons learned, which contribute to the development of the Customs control mechanism in France as well as the tactical strategies on the ground.

Between the 18th and late 19th centuries, French Customs units were developing – quite separately from any industrial programme – various models of folding beds that could be transported in backpack form. They made it possible for Customs officers to remain silent and still for hours at a time whilst on the lookout for smugglers. This “nightwatch bed” (“lit d’embuscade” in French, literally “ambush bed”)[1] is an iconic object showcasing the ingenuity and operational innovation of the Customs profession.

The underlying principle of the nightwatch bed of old, namely to “see without being seen” before taking advantage of the element of surprise and springing into action, is embodied nowadays in the tactical camera. This image-capturing device can be placed in a key position as part of a surveillance system (ideally at an observation post, although keeping this surveillance mechanism covert is problematic for Customs officers) or on an airborne mobile device (such as a drone or helicopter), on a temporary basis and without the smugglers’ knowledge. The use of such cameras has been trialled in France to support “traffic” controls, which involve setting up covert Customs surveillance operations on domestic roads.

Covert surveillance: Daily working hypothesis for inland Customs

The image of a Customs officer standing at a barrier has never been anything but an illusion. The annals of French Customs are brimming with references to surveillance mechanisms, including use of the famous folding bed for ambushing convoys of smugglers on the roads and at border crossing points that were not permanently manned. However, over the years, this method of covert surveillance work would be codified.

A significant turning point was reached in 1993 when the internal borders within the European Union (EU) were abolished. This phenomenon gave rise to a new body of principles governing the use of Customs services and created a new relationship between Customs and the territory in which it operated. First of all, services were regrouped across the major transit routes such as the ports and airports serving the Union’s external borders. Secondly, in order to gain an insight into the monitored intra‑European flows (goods in transit, products subject to excise duties such as alcohol and tobacco products, and prohibited products such as counterfeit goods or narcotic substances), Customs authorities developed new control techniques, including inspections in warehouses and inside businesses, as well as “traffic checks”.

These traffic checks quickly garnered enthusiasm among Customs administrations and Customs officers alike. Various “second-level” Customs services were then established in a number of European countries (e.g. Germany, Poland and Italy). France set up its own domestic surveillance units (“brigades de surveillance intérieures” (BSIs)) with 2,741[2] officers on the payroll, making up approximately 45% of France’s land-based Customs workforce.

These checks are, in fact, part of the daily covert surveillance operations by Customs. The operations are embedded deep within the transit routes, meaning that a broader variety of fraud routes and bypass options can be covered. In this way, this covert surveillance concept can be applied as a response to the concept of the “smuggling basin”, a border area stretching into the hinterland and ripe for smuggling activity across the national territory. This smuggling basin is familiar territory for Customs officers; they have to be fully acquainted with the topography of the transport network and border areas, the secondary roads, the routes used for bypassing possible roadblocks and the key road junctions, but they also need to know specific locations and their capacity for storage, stopping and transshipment. The Customs services therefore needed to improve their working methods and increase their local knowledge.

After 1993, these methods were gradually codified as the Directorate General introduced a number of all-encompassing texts enshrining many tactical practices that had been rolled out on the ground (the use of regional topographical documents, the installing of motorway tolls and secondary exits, dynamic checkpoints with or without motorcyclist teams, decoys, stealth operations,[3] etc.).

Set against this new background of enforcement and checks, where mobility became the prerequisite for commanding control over the territory, technology was initially the Customs officer’s enemy. General and widespread accessibility of mobile phones has allowed traffickers to set up workarounds to the controls by warning their fellow traffickers within organized convoys of the Customs presence. Large-scale fraudulent organizations do not hesitate to use military technologies, such as locator beacons or satellite telephones, to evade detection by the listening devices operated by the various investigative units. Since the 2010s, smartphones and the internet connectivity they deliver have made the tactics required for controls even more complex.

Customs authorities reacted by integrating similar technologies, combining the communication of different types of information and geolocation. A 4G-based secure radio network emerged. Known as AGNet,[4] this tool is tailored perfectly to the needs of the units for which it was clearly designed (motorcyclist integration, emergency button function, geolocation facility, tactical wire function, etc.). More recently, Customs has been trialling the use of ground and aerial tactical cameras.

The tactical camera: a promising device under trial

Trials have been conducted by French Customs’ new centre of expertise for drone technology, which has been assigned to provide support on demand for land-based services and for key advisers[5] in the Customs units, which are the real driving force behind this innovative spirit that relies on a local culture of openness to change from the bottom up.[6]

On the ground, the decision was taken to use hunting cameras. The equipment cannot be used to identify individuals or vehicles specifically, but it is suitable for monitoring small areas (such as car parks or motorway laybys) and for observing the arrival of a vehicle as well as noting its size and model and – if they get out – the behaviour of its occupants. The use of more detailed viewing methods would be subject to specific administrative authorization in advance (from CNIL[7]) or authorization from judges in judicial investigations, given that such use is inconsistent with everyday detection work.

Discreet hunting cameras[8] have been connected up to a 4G image transmission system. These robust systems can be disassembled and are relatively inexpensive. However, sufficiently experienced Customs personnel are needed to operate them, using their expertise to identify abnormal movements and fit them strategically for the most effective outcome within an operation (ensuring optimum positioning of cameras, and knowing how to make best use of the warnings issued and carry out verifications effectively).

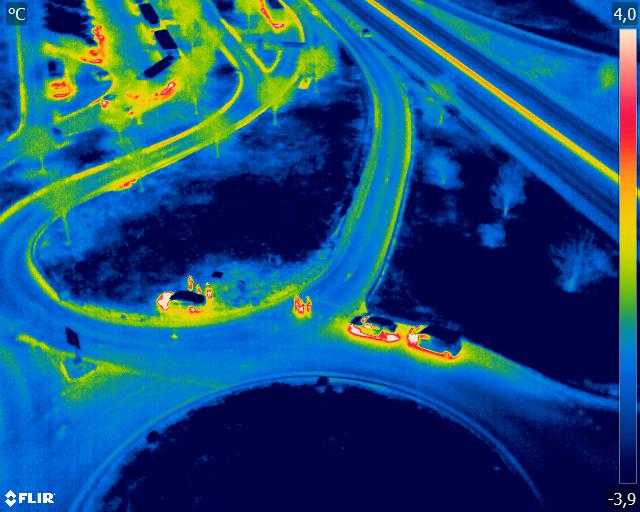

The cameras installed on helicopters[9] operate a superior optical system to those positioned on the ground (greater zoom capacity, thermal imagery capability). The main obstacle to their regular use is the cost of maintaining and mobilizing helicopters as well as pilot availability.

Drones operated by the centre of expertise, use of which is regulated under the new legal framework established by Law No. 2023-610 of 18 July 2023,[10] are now piloted remotely by licensed pilots from the DNGCD, which conducts test flights over a number of land areas within French Customs territory.

Lessons learned and conclusions drawn

These tactical cameras are proven to be invaluable tools for Customs officers, as they offer a means of real-time surveillance that is workforce-efficient and effective.

Use of the camera on the ground enables units to be one step ahead for the purpose of intercepting vehicles and, potentially, to have additional behavioural “selection criteria”, identified upstream, at their disposal for their response at checks further downstream. Lastly, the viewing of the relayed images can also facilitate post-operation analysis in the course of feedback. Its low price and reasonable cost of maintenance, and the short training time frame required for the use of this equipment (approximately one day) are all arguments in favour of its broader deployment.

The helicopter and camera have already proven effective, in particular in visual pursuit exercises where the target refuses to surrender. The helicopter/camera coupling also makes it possible to detect suspicious conduct upstream of a surveillance mechanism. A camera fitted to a helicopter can take aerial photos several tens of kilometres apart and along various routes for comparison purposes (for example, capturing the number of vehicles parked before and after the surveillance system has been installed). Fully integrated in a land-based system (in terms of the mission, command, resources, transmission and regularity), helicopter support has already facilitated combined ground/air operations and the establishment of major findings. Investment in staff and upgraded equipment or the pooling of resources with other military or civil departments would contribute to the further development of this highly valued support.

The drone itself has also become a particularly beneficial platform for additional uses. Assigned to an observation sector, it can be used both as “remote aerial observation binoculars” for spotting suspicious behaviours in the traffic upstream (offloading of goods, parking on the hard shoulder, making U‑turns and suddenly turning off, etc.) and also for securing the control area (with recording capability). The obstacles to using such drones include the current low numbers of staff available to pilot them remotely (and, therefore, the lack of regular availability of this resource), the range (some 5 km for the current models) and the endurance of Customs drones generally (around 25 to 30 minutes, thus requiring frequent battery changes). Drones will probably become increasingly commonplace for use in Customs operations, with officers operating small, less costly civil drones, which will push up the demand for remote pilots.

Conclusion: trialling, evaluating, mapping

Trials have shown that French Customs would benefit from exploring further the use of the tactical camera in its everyday detection devices. Cases of fraud identified in this context are established most of the time not on the basis of prior intelligence but as a result of swift tactical exploitation of the reaction of a suspect vehicle in the traffic flow. A camera would facilitate an even more proactive approach and would not be dependent essentially on prior operational intelligence or on mere luck. The availability of human resources and the training of Customs officers are genuine issues here but do not in themselves present a challenge. In making the final preparations for the use of tactical cameras, two elements still require work.

The first involves their consideration as an evaluation tool. Just as departments are subject to a performance policy, technical resources could become subject to monitoring indicators which measure their longer-term cost, their usability in real conditions (for example, how many hours are spent airborne per month by one drone, taking meteorological conditions into account?) and their results (in which operations did their use play a decisive role?).

The second element concerns the need for a greater geographical and analytical culture: where and when to use cameras remains the tactical question upstream of operations. Currently, the geographical culture promoted by Customs is too weak; experienced Customs officers rely on an empirical knowledge of the terrain and, as they transfer to new positions or take up retirement, the result is a significant draining of knowledge from the field services. How can we harness this empirical knowledge? How can we build a Customs knowledge of the territory and of potential smuggling basins so as to be proactive and know where to deploy the cameras?

More information

cedric.orgeret@douane.finances.gouv.fr

[1] See on the Centre d’Histoire Locale de Tourcoing (Tourcoing Local History Centre) website at: http://chl-tourcoing.fr/Collections/Zoom-sur-les-collections/Vie-publique/Lit-d-embuscade.

[2] Figures as at July 2023 – includes motorcyclists and dog/handler teams but excludes other land-based services at the borders (such as the External Surveillance Units (BSEs)) or specialized support services (Customs Operations Centres (CODTs), scanner lorries, etc.).

[3] “Stealth operations” means involving regular relocation during an operation to create confusion among traffickers.

[4] Presentation of the AGNet tool in Douane infos, September 2021.

[5] Thanks in particular go to CP Nicolas Buffe and to ACP2 Davroux of the Nogent-sur-Oise unit for their work.

[6] “Bottom-up innovation” means that the administration promotes ideas from the bottom upwards through collaborative or participatory methods (as opposed to innovation emanating from the top downwards only). This approach sometimes allows the local services to trial technologies and to use the results in the main decision-making services. Trialling one technology over another is therefore determined at the initiative of local Customs managers who are familiar with and choose the units for conducting such trials.

[7] Commission Nationale Informatique et Libertés (France’s National Data Protection Agency) which oversees the collection of individual data in France and ensures compliance with the principles of law.

[8] Off-the-shelf and reasonably priced small hunting cameras with movement detection function (to capture the arrival or departure of a vehicle, or the movement of individuals even in darkness – as used in game hunting).

[9] Airborne assets have been used in Customs operations since the 1960s. They have been developed mainly in the maritime/coastguard context which in 2018 established a fully-fledged department with national competence, the National Customs Coast Guard Directorate (“DNGCD”), comprising a fleet of 31 vessels and 15 aircraft (Beechcraft King Air 350 twin-engined turboprop aircraft and EC135 helicopters). The air/land component is provided by the Air/Land Surveillance Unit (“BSAT”) based at Margny-Les-Compiègne (Oise).

[10] Providing Customs with the resources needed to handle new threats (Article 22 amending Article L 242-5 of the Domestic Security Code) which permits the use of “cameras fitted to aircraft” by Customs for some operations.