Container scanning: analysis of the mechanism’s impact on the Customs clearance procedure established in Cameroon

6 June 2019

By Cameroon CustomsIn 2016, the Cameroon government opted to impose a systematic scanning policy for containers on both their import and export. This article assesses the impact of this mechanism in the Customs clearance procedure, focusing, in turn, on its efficiency, how it is generally perceived by private‑sector importers and stakeholders, and the difficulties created by its implementation.

On 26 June 2006, a mobile scanner was installed for the first time at the Port of Douala, in accordance with resolutions resulting from the reform process undertaken by Cameroon Customs under which a scanning process was to be integrated into the clearance procedure for imports of sea containers. The resolutions were the result of consultations between representatives from an inspection company, the Autonomous Port of Douala (PAD), private sector undertakings and port supply chain stakeholders assembled within Cameroon’s National Trade Facilitation Committee.

The key objective of deploying a scanner is to reduce significantly the time needed for inspecting containerized goods by substituting non-intrusive inspection (NII) for the physical inspection of goods, which generated extensive costs and caused multiple burdens and annoyances for importers.

Although the majority of stakeholders in the port supply chain concurred as to its necessity, the initiative generated various pockets of “internal resistance”[1] within a not-insignificant fringe of Customs officials who questioned the tool’s efficiency as well as the methodology for its use in the clearance process.

This initial scanning equipment was a first-generation mobile scanner procured under an agreement between the State of Cameroon and the inspection company concerned, and was installed on a 60 m x 35 m site adjoining the container park at Douala International Terminal (DIT), the approved operator of the container terminal at the Port of Douala. The equipment had a maximum operating capacity of 20 containers per hour and was operated from 06.00 to 18.00.

The increase in the volume of containers unloaded at the Port of Douala, the recurring breakdowns of the equipment over the years, the cumbersome procedures inherent in the protocol for scanning, the need to enhance enforcement and combat large-scale trafficking, and the security issues created by the crises in the Central African sub-region and the English-speaking regions of Cameroon prompted the government to take the gamble of introducing scanning technologies that were more sophisticated and better adapted to contemporary circumstances.

Accordingly, in September 2016, three fixed scanners with a total effective scanning capacity of 150 containers per hour were brought into operation, still in the context of a partnership between the State of Cameroon and the inspection company. In a major development, the government opted to impose a systematic scanning policy for containers on both their import and export.

In order to assess this policy’s impact on the implementation of the clearance process for containers at the Port of Douala, Customs felt that it was necessary to look at the current positioning of the scanning process in the mechanism for examining containerized goods, the tool’s efficiency, how it is generally perceived by private sector importers and stakeholders, and the problems created by its implementation.

Repositioning the scanner upstream of the clearance procedure

In 2006, mobile scanners had been positioned at the end of the Customs clearance procedure, and containers were subject to the scanning process only where:

- declarations were made in the red channel;

- declarations were made in the yellow channel and were subject to scrutiny by the relevant visiting inspector;

- the nature of the shipment made a physical inspection necessary, for instance, owing to a security alert being triggered;

- an accelerated procedure was under way, such as the unloading of cargo by means of hoists (from vessel to lorry, thereby avoiding any storing or depositing on the quays) and the direct unloading of cargo (from vessel to Customs-bonded warehouse under cover of a summary declaration);

- the goods were being transferred to an external Customs storage facility.

This original mechanism was heavily criticized: access to images was restricted to those officials working in the Scanning Management Unit only – with all the risks of collusion this might entail, mobile scanners operated at a reduced capacity, and the quality of the images produced was relatively poor. Lastly, and most importantly, users complained about the cumbersome process, from the initial scheduling of an appointment to the scanning operation itself, and the physical inspection ensuing in the event of cargo being suspect, an inspection which, naturally, gave rise to new costs.

The situation changed in late 2016 when the new scanners were brought into operation. Two‑dimensional X-ray scanning was rolled out on a systematic basis. For imports, scanning became a prerequisite to the container’s storage in the container terminal at the Port of Douala following its unloading.

The visiting inspectors from frontline offices are systematically required to consult the scanned images before issuing a release note for the goods concerned. Having access to images uploaded onto their IT network allows Customs inspectors to take decisions more quickly. All Customs personnel have access to the image, which means that whenever a frontline inspector has taken a decision, the second-line inspector and the port authorities can refer to the instructions issued more readily.

As regards deferred inspection services, they now have access to a database allowing them to assess and carry out some cross-checks and analyses on cargo that has already been unloaded, or even to confirm suspicions raised during an audit or in the light of specific intelligence received.

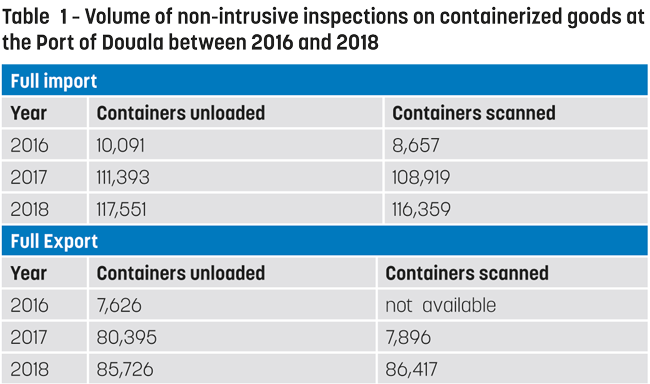

According to the spokesperson for the inspection company responsible for operating the new scanners at the Port of Douala, the undertaking actually scans 35 containers per hour on average, but it could, in theory, scan 50 containers per hour. Table 1 shows the volume of non-intrusive inspections of containerized goods at the Port of Douala on import and export alike over the 2016‑2018 period.

Efficiency of the new scanning approach

Although it is undoubtedly very difficult to assess and quantify accurately the efficiency of the scanning tool on the clearance process, its impact on the time taken by Customs services in processing the files for containerized goods cannot be overlooked. The results of a recent study on the time required for goods to be imported at the Port of Douala clearly indicate a reduction in the time taken in comparison to the last study published in 2012.

As regards enforcement, systematic scanning has facilitated the detection of a number of cases involving the smuggling of heavily taxed goods (for example, wines and champagne concealed in “diplomatic” shipments) and prohibited goods (for example, the seizure of 75 kg of cocaine and undeclared weapons and ammunition in various containers registered to private individuals).

Perception by the operators

Importers and licensed Customs brokers have welcomed the pronounced drop in the number of visits made to the quayside, especially in the light of the additional costs incurred in those operations. The costs involved in import lifting, that is to say, the operation whereby containers are lowered onto the terminal site and subsequently loaded onto a means of transport, rose to 105,000 CFA francs (approx. 150 euro) for 20-foot containers and to 180,000 CFA francs (approx. 270 euro) for 40-foot containers, but these costs did not include those involved in retaining access to transport, which amounts, on average, to 100,000 CFA francs per day.

According to Nguene Nteppe, the Permanent Secretary of Cameroon’s National Trade Facilitation Committee (CONAFE), which brings together public and private sector operators to address cross-border trade issues, the repositioning of the scanning procedure has had a positive effect in simplifying formalities, thereby resulting in greater procedural coherence.

Difficulties

Although the above developments appear to paint quite a rosy picture, some aspects of the mechanism for using the new scanners are still the focus of criticism.

Costs involved

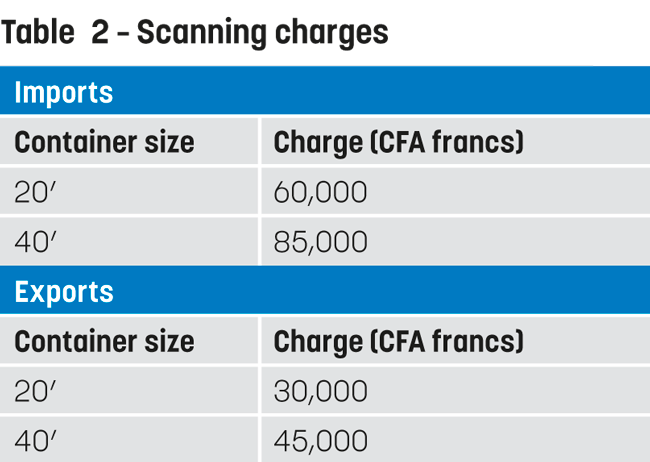

The main criticism focuses on the costs involved in using the tool. Nteppe claims that systematic scanning has increased the costs of transactions, in terms of imports and exports alike, and that this rise in costs is a major concern for operators. The charges applied were not established under the normal procedure for approving port tariffs, namely where all objective factors are analysed with a view to setting a tariff that is both balanced and fair. Notwithstanding CONAFE’s questioning of the Minister for Finance on this matter, this charging procedure was still not applied.

The current charge imposed for scanning, set out in Table 2, is, therefore, considered to be very high and ought to be revised. That said, in the light of strong criticism from exporters and freight forwarders, it has since been amended,[2] and the scanning of empty containers is no longer subject to a scanning charge.

A further point raised by Nteppe is that the inspection charge is still at 0.95% of the FOB value of the goods concerned, subject to a minimum collection of 110,000 CFA francs,[3] whereas, at the same time as the introduction of the systematic scanning of containers, the contract binding the State of Cameroon and the inspection company under the Import Verification Programme has been revised to remove the preshipment inspection procedure.

Relations with licensed scanning service providers

The structure of the systematic scanning mechanism at the Port of Douala calls for collaboration between two separate stakeholders, namely DIT – the operator of the container terminal – and an inspection company, which holds the licence for providing the public scanning service.

Statistics for the 2016-2018 period (see Table 1) have shown how the systematic scanning of containers has not, strictly speaking, become genuinely operational:

- In terms of importing goods, one of the explanations given for the discrepancy between the number of containers unloaded and the number of containers scanned is the fact that DIT negotiated individual agreements with various stevedoring operators, so that those operators could provide port handling operations for shipments in their charge according to their tailored schedule. In the event of a failure to make handling equipment (tractors and semi-trailers, highlifters, etc.) available, scanning sometimes does not take place.

- In terms of exporting goods, there is a lack of statistics on empty containers. As already explained, the government, following negotiations with supply chain stakeholders, decided that the scanning of empty containers for export would be free of charge. However, because of the operating costs borne by the licensed provider, it no longer carries out these operations. The situation could pose risks, and, furthermore, there have been reports of one container, supposedly empty when shipped from Cameroon, being recovered in Italy with a vehicle inside.

Export procedure

The current positioning of scanning equipment is still unsuitable, given the requirements inherent in the export procedure in force at the Port of Douala. Again, Nteppe takes the view that the scanning procedure should take place outside the container terminal, for the sake of consistency with the sequencing of export procedures.

This is all the more relevant, bearing in mind that containers intended for export are conveyed to the terminal by carriers authorized by the exporters themselves or their approved Customs brokers, and that the protocols governing referral and movement inside the terminal provide no guarantee that all such containers will undergo scanning systematically prior to the exiting of the rolling stock that transported them there. Consequently, some containers are stored without being scanned and must then be subjected to further lifting, thereby incurring additional costs.

Conclusion

It cannot be disputed that the systematic use of scanners in the clearance procedure provides many advantages as regards both the simplification and the broader facilitation of procedures. However, implementing such a mechanism, especially in developing countries that rely on the expertise of inspection and operating companies at port terminals, requires optimal collaboration between all economic operators and stakeholders in the supply chain.

More information

[1] Thomas Cantens, in his article entitled “Un scanner de conteneurs en ‘Terre Promise’ camerounaise: adopter et s’approprier une technologie de contrôle,” published on the website www.openedition.org in 2015, illustrates the contingencies observed in the adoption and effective use of this tool by Cameroon Customs.

[2] See Circular No. 013 of 27 January 2017 establishing the arrangements for assessing and paying the scanning charge and Directive No. 016605/MINFI/CAB of 10 November 2017, issued by the Minister of Finance, laying down the procedures for assessing, collecting and repaying the scanning charge.

[3] Ministerial Directive on the PVI (Import Verification Programme) of 30 November 2016.