Internet domain name ownership data: understanding changes and useful suggestions for Customs

22 June 2020

By Brian J. King, Director of Internet Policy and Industry Affairs, MarkMonitorComputers identify websites with an IP address, a long string of numbers separated by periods, which are difficult for humans to remember. Websites also have an address, made up of alphanumeric letters that usually spell out a word or brand name, called a domain name.

Since the creation of the internet as we know it, internet domain name ownership information has been publicly available in a database known as “WHOIS” – i.e. “who is” the owner of a domain name. Like other public databases of information pertaining to land title, trademark registration, or business entity ownership, WHOIS data serves the public interest in several ways, including as an important tool for law enforcement authorities. Richard D. Green, Chair of the G7 High Tech Crime Subgroup, recently wrote, “Supporting investigations related to phishing, malware, ransomware, counterfeit products, child sexual abuse material and terrorism, among other offences, as well as to facilitate the identification of victims and offenders, goes to the essence of providing domestic security for the citizens of G7 members. As such, WHOIS constitutes a key element of online accountability.”[1]

However, the availability of this data to law enforcement authorities and other good actors has been significantly reduced as a result of the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which went into effect in May 2018. Overreaction based on fears of GDPR’s potential for crippling fines and business shutdown orders has led to broad misapplication of the law. GDPR is currently being misapplied both inside and outside the EU, resulting in domain names being listed in the WHOIS without personal data, significantly diminishing the usefulness of WHOIS to law enforcement authorities. While work is currently underway to correct early over-application of the law and build a system to facilitate standardized access to this data, one of the most important tools for online law enforcement investigations hangs in the balance. More information follows, including ways governments can help improve the outcome of this internet policy development, as well as resources and best practices for Customs agencies to access WHOIS data in the short-term while these policies are being developed and implemented.

Background

In many ways, the ability to access WHOIS data has long contributed to trust in, and the security and stability of, the global Domain Name System (DNS), the hierarchical and decentralized naming system for computers, services, or other resources connected to the Internet or a private network. In the early days of the internet, many of today’s universal protocols were still being developed, and WHOIS data was often needed to contact system administrators to resolve technical problems with domain names and the systems that used them. Today, the internet’s very existence still requires the universal, voluntary use of standardized protocols, i.e. all systems communicating with each other in the same way. The ability to notify administrators when systems behave in a way that is inconsistent with those protocols remains as important as ever to the continued success of the internet.

Similarly, for the past several decades law enforcement authorities, cybersecurity investigators, intellectual property owners, and everyday consumers have come to trust WHOIS data to verify that website owners and email senders are who they claim to be. Because of the extraterritorial nature of the internet, there is no global internet police force, and no single entity can make global laws for its use. Rather than having an internet police force, the global DNS relies on local law enforcement, independent cybersecurity experts, IP owners, and consumer protection agencies to contribute in their own way, and WHOIS has been described as the “first line of defence,”[2] enabling good actors to engage in self-help in order to address technical and legal problems for the greater good.

Registry, registrar and registrant

There are three different roles involved in the domain name registration process: the registry, the registrar, and the registrant. A domain name registry creates domain name extensions, sets the rules for domain names, and works with registrars to sell domain names to the public. For example, Verisign manages the registration of .com domain names and their DNS. The registries manage large, centralized databases with information about which domain names have been claimed and by who.

The registrar sells domain names to the public for a certain period of time and updates the registry when a customer purchases a new domain name. Some have the ability to sell top-level domain names (TLDs) like .com, .net and .org, or country-code top-level domain names such as .us, .ca and .eu. Lastly, a registrant is a person or company that registers a domain name.

What data is available?

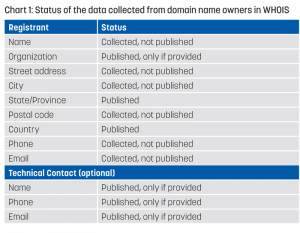

Data collected from domain name owners includes the name, organization (if applicable), postal address, email, and telephone number of the owner, known as the domain name registrant. Domain owners may also provide additional information for a technical contact (e.g., an outsourced technical service provider), if applicable. While this might seem like a wealth of information to Customs agencies for whom woefully minimal data about shipments and shippers is the norm, only a very limited subset of the WHOIS data collected is public. See chart below for comparison:

The result is that very little helpful information is available publicly, but more data is available to law enforcement authorities upon request. Information on how to request this data follows.

Who controls the data?

While many countries have laws governing content on internet websites, the global DNS that routes traffic and serves as a source identification for websites and email is coordinated through a multistakeholder governance model. In the late 1990s, the nonprofit Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) was formed to globalize domain names and IP address numbers, which were managed under a contract controlled by the US Department of Commerce before being handed over to ICANN. In this multistakeholder governance model, governments collectively account for just one advisory committee among many other stakeholders, including private intellectual property and non-commercial civil society interests.[3]

In order to promote competition and consumer choice in the domain name industry, ICANN serves as a regulator for the domain name registrar industry, accrediting thousands of registrars to ensure domain name owners enjoy the benefits of choice and competition among registrars. ICANN also contracts with registries. Registrars and registries together are known as “contracted parties” in that their business is dependent on their non-negotiable contract with ICANN. Registrars compete for customers based on domain name pricing, availability of security features, and value-added services like website builders and email hosting. At the most functional level, registrars perform the basic technical task of adding a domain name to the global DNS and renewing it each year. As part of this core function, each registrar is responsible for storage and some level of accuracy validation of WHOIS data for every domain name under its management.

What’s happening today?

Since the entry into force of the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in May 2018, ICANN requires registrars to make a minimal subset of public WHOIS data available to all internet users upon request, both via a publicly accessible server responding to computer-generated requests, and in a user-friendly format on each registrar’s website. But the non-public WHOIS data remains hidden from law enforcement and other parties with a lawful basis for accessing the data due to the risk of violating the data protection law. While ICANN’s stakeholders work to develop policies to enable standardized access to redacted WHOIS data for such entities, ICANN unilaterally conscripted its contracted parties into manually evaluating requests for non-public data via a “Temporary Specification.”[4] Unlike normal ICANN policy development that must be based on consensus among its stakeholders, a “Temporary Specification” is cramdown, non-negotiable, short-term policy.

Unfortunately, by many accounts, the Temporary Specification has been an abject failure. In the first nine months of the GDPR and the Temporary Specification being in effect, MarkMonitor, the global leading online brand protection service provider, submitted over 1,000 separate requests to registrars for non-public WHOIS data.[5] These requests were manually reviewed and sent by the world’s top brand protection analysts and were related to websites confirmed to be infringing on more than 15 world-famous client brands. Of these requests, 86% were either ignored for 30 days and deemed denied, or were explicitly denied without any indication that the request was actually considered. Anecdotally, many law enforcement requests have similarly fared badly. Another troubling anecdote arose during the ICANN66 Montreal meeting in November 2019 when ICANN reported that a registrar had sent a generic denial message to an EU Member State’s data protection authority, which was investigating a data breach on a website using a domain name sponsored by the registrar.

Progress and best practices

The first phase of ICANN’s Expedited Policy Development Process (EPDP) focused solely on the collection of WHOIS data and the public availability of a minimum subset of this data. Phase 1 has now been concluded, pending implementation formalities. To the disappointment of many in the IP and the law enforcement community, Phase 1 largely confirmed the requirements of the Temporary Specification into permanent ICANN consensus policy for one-off, registrar-decided disclosure of non-public registration data. Law enforcement authorities and the IP community now rely on Phase 2 of the EPDP to deliver a system for standardized access to non-public WHOIS data.

In response to this Phase 1 policy, the Registrar Stakeholder Group published guidance for WHOIS data requestors on how to submit a one-off request for non-public WHOIS data.[6] This guidance is non-binding on registrars and will not guarantee disclosure of WHOIS data to law enforcement authorities for any given request. However, following this guidance should provide the best chance of successfully achieving disclosure of WHOIS data at a registrar’s discretion. Another development from the EPDP’s Phase 1 policy is that each registrar must publish its policy and process for handling one-off disclosure requests on its website. While this requirement is not yet in effect, some of the largest registrars have already provided this guidance. MarkMonitor’s registrar policy may be viewed here[7] for reference.

While some registries and registrars have been unresponsive to private sector requests, many are happy to work with law enforcement organizations who wish to request WHOIS data. Customs administrations may identify the registry and registrar for a given domain name by submitting a WHOIS query through any number of public lookup utilities, including MarkMonitor’s free public WHOIS[8], and then contact that entity directly. Many registries will list their law enforcement policies and processes on their website, and the contact information for each registry is publicly available.[9] Registrars are also contractually obligated to list their abuse complaints processes on their website, and many include specific instructions for law enforcement agencies. Several law enforcement organizations have relationships with many popular registrars, and can assist Customs administrations in making these requests more successfully. Such groups include the Europol Cybercrime Centre (EC3)[10] and the National Cyber-Forensics and Training Alliance (NCFTA)[11], as well as multinational groups including the Joint Cybercrime Action Taskforce (J-CAT)[12], and the Intellectual Property Rights Coordination Center (IPR Center)[13].

An Initial Report on Phase 2 of the EPDP has recently been published for public comment on a proposed System for Standardized Access/Disclosure (SSAD) of non-public WHOIS data.[14] The Initial Report includes details on how entities can become accredited to access WHOIS data and what information will be required to grant access to this data. Importantly, the Initial Report includes the concept of automated access for law enforcement authorities within their jurisdiction, though it lacks clarity on how other requests will be approved or denied, who the “data controller(s)” will be (an important factor in data protection law), and how the SSAD can evolve and gain efficiencies over time as data protection law evolves.

What can be done?

Due to the global coronavirus pandemic and the publication of the Phase 2 Initial Report Addendum[15], the deadline for public comments on Phase 2 of the EPDP Initial Report has been extended until 5 May 2020.[16] Law enforcement interests are represented in the EPDP and in the ICANN multistakeholder model, generally through the Governmental Advisory Committee (GAC). GAC members are often designated by a jurisdiction’s telecommunication agency, cybersecurity agency, or similar entities. Customs agencies are able to find out which governmental agency in their jurisdiction serves as a liaison point to the GAC by searching here[17].

MarkMonitor is pleased to represent the IP constituency within ICANN’s multistakeholder model in the EPDP, and to help advocate for our law enforcement partners with whom we share a valued relationship. We welcome any thoughts and input from our global Customs partners, and remain available to discuss the EPDP and other global policy matters.

More information

Brian.King@markmonitor.com

www.markmonitor.com

[1] https://www.icann.org/en/system/files/correspondence/green-to-chalaby-21jun19-en.pdf

[2] https://www.igfusa.us/remarks-of-david-j-redl/

[3] https://www.icann.org/community

[4] https://www.icann.org/en/system/files/files/gtld-registration-data-temp-spec-17may18-en.pdf

[5] https://www.markmonitor.com/mmblog/brand-protection/gdpr-whois-and-impacts-to-brand-protection-nine-months-later/

[6] https://rrsg.org/minimum-required-information-for-whois-data-requests/

[7] https://rrsg.org/minimum-required-information-for-whois-data-requests/

[8] https://domains.markmonitor.com/whois/

[9] https://www.iana.org/domains/root/db

[10] https://www.europol.europa.eu/about-europol/european-cybercrime-centre-ec3

[12] https://www.europol.europa.eu/activities-services/services-support/joint-cybercrime-action-taskforce

[13] https://www.iprcenter.gov/

[14] https://www.icann.org/public-comments/epdp-phase-2-initial-2020-02-07-en

[15] https://www.icann.org/public-comments/epdp-phase-2-addendum-2020-03-26-en

[16] https://www.icann.org/news/blog/epdp-team-publishes-addendum-to-phase-2-initial-report-for-public-comment