Using Customs data to follow crisis trends: the experience of Niger Customs

21 October 2020

By Mahamat Akanja, Thomas Cantens, Mahamane El Hadj Ousmane, Hassane Moumouni and Ibrahim SouleyTo date, African countries have been only moderately affected by the COVID‑19 pandemic.[1] Governments took measures promptly: as early as March 2020, borders were closed except for goods, large gatherings were banned, curfews imposed and capital cities locked down, teleworking was introduced in education and public services, and social measures were adopted to compensate households for loss of income (in Niger, water and electricity were supplied free of charge to the poorest households for three months). These measures were gradually eased from the start of June onwards.

Customs in Niger kept up the same level of presence and activities as before the crisis, while complying with health precautions (social distancing, including, in particular, new vehicle search procedures, the wearing of masks and gloves and the availability of hand gel and soap). Measures common to most Customs[2] were also adopted:

- imports of equipment and products used to tackle the epidemic were exempted from duties and taxes; they were selected in line with the list of products recommended by the World Customs Organization;

- the Customs bond was extended by 15 days to 90 days;

- current investigations were suspended;

- a crisis unit was set up for the purpose of coordinating activities.

The purpose of this article is to examine a specific aspect of Niger Customs’ response: the use of Customs data to follow the trends in the crisis and support the Government in the almost daily preparation of responses to health and social concerns.

The specific features of the COVID‑19 crisis and Customs involvement

The consequences of this crisis and the counter-measures taken by governments, such as lockdown and the closure of borders, were difficult to predict. At the start of the crisis, analyses indicated dramatic effects on economic cycles: a drop in imports of consumer products (rice, pasta, cooking oil, sugar, cereals); disruption of the flow of pharmaceutical products from Asia; a fall in exports of mineral resources as a result of the drop in demand in high-income countries and difficulties in delivering mineral exploitation equipment; a drop in exports of agricultural and animal products, ultimately leading to higher prices or even shortages; food insecurity; and a drastic drop in tax revenue at a time when the Government might most need it.

Although the negative effects of the crisis are undeniable, it is worth considering how to “follow” a crisis as unprecedented as COVID-19 more closely, so that counter-measures can be regularly adapted. Governments are managing to produce figures on a daily basis on the health situation of the country (numbers of tests, patients treated and deaths), but gaining access to figures on the economic situation in short timescales is a complicated matter, particularly during an extraordinary event which, by definition, has inevitably disrupted forecasting.

In this context, Customs data are particularly useful to the Government of Niger. On the one hand, they show trends in imports of staple goods and exports of raw materials. On the other hand, they demonstrate the almost immediate effects of the lockdown measures and restrictions on transport and border crossings on the production and flow of material goods. Unlike the crisis of 2008, which was primarily financial, the effects of which spread with a time lag, the COVID‑19 crisis is a material crisis. Customs data therefore became critical information for the Government. In practice, they were the only “instant” economic data on the crisis to which the Government could have regular access.

Customs in Niger therefore had to adapt its method of reporting to the Government, moving from monthly reporting to daily and weekly reporting. Two Customs officials attended the meetings of the statistician-led national crisis unit. Their role was to share Customs data and take part in the regular review of forecasting models for revenue and economic activity. Internally, weekly monitoring was introduced for import and export flows according to the exporting regions and national Customs offices, and for exemptions applied to products used in tackling the pandemic.

What does “following” crisis trends mean?

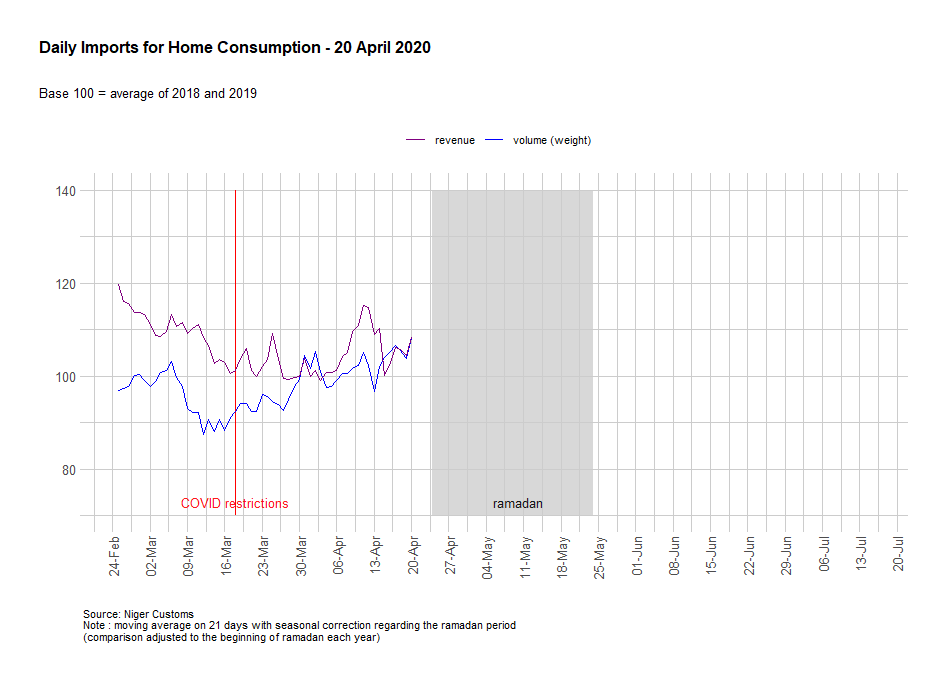

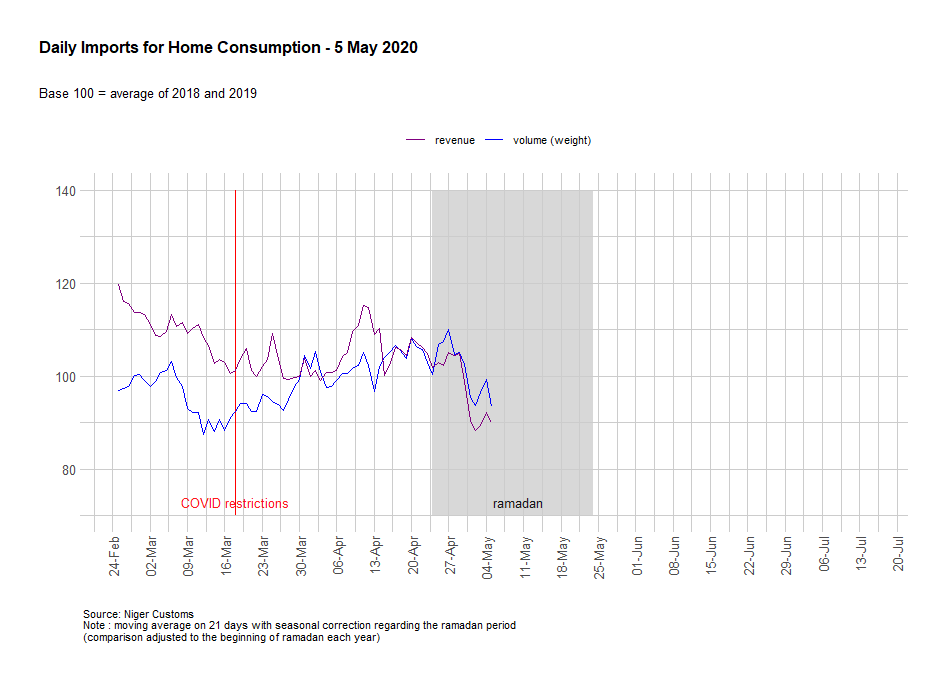

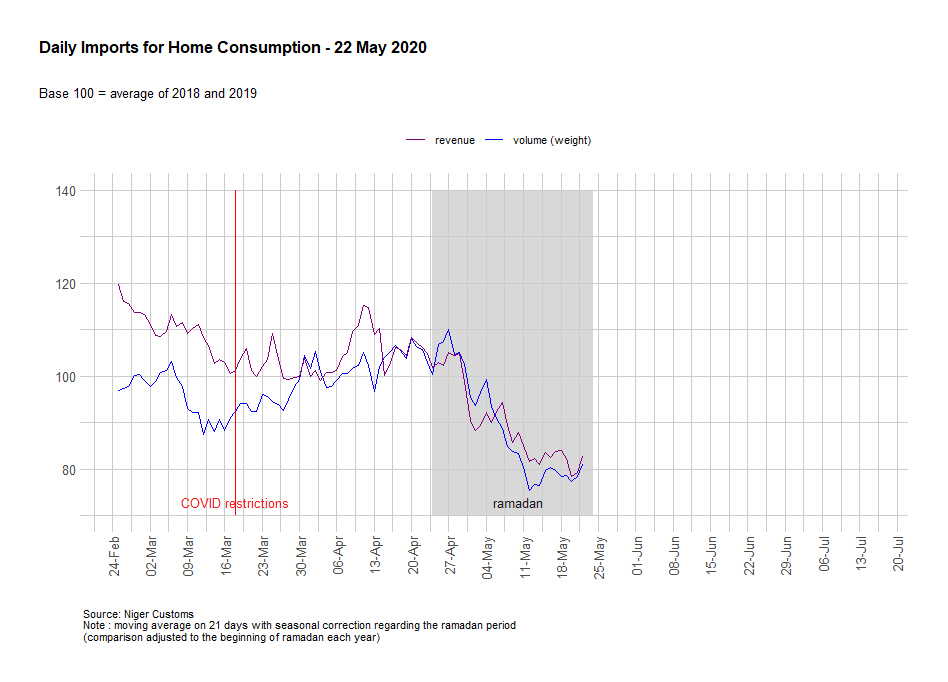

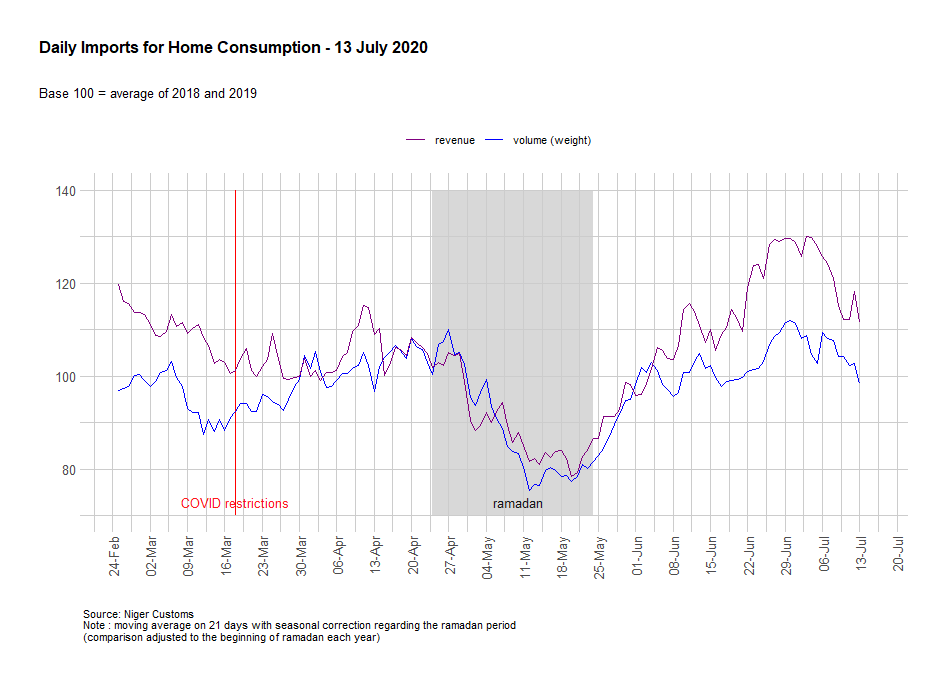

Following the crisis is mainly about comparing data for the crisis period with those for the preceding months and years: comparing the trend in variables, such as revenue and volumes imported by region, by type of operator and by trade route. This process of monitoring raises two technical issues, and solving them was, in itself, an interesting lesson for Customs.

The first issue was how to reveal the crisis while the crisis was in progress. Customs and tax administrations are accustomed to producing and analysing data aggregated on a monthly and annual basis. At a time of crisis, these aggregated data are not enough.[3] They are drawn up retrospectively, and with too great a time lag to allow the government and the administrations to react in time. Customs in Niger chose a daily timescale, using moving averages[4] and comparison with the average for dates in 2019 and 2018 to smooth out the sharp daily variations and reveal the weekly trends.

The second technical issue involves distinguishing between what is a result of the crisis and what is caused by other factors. A robust estimate of a causal inference between the crisis and variations in revenue or volumes can be made from retrospective analysis. During the crisis, the approach was aimed at swift quantitative documenting of trends in the situation and of what was and what was not attributable to the crisis. Rather than estimating the effects of various factors on revenues and volumes, known variation factors needed to be removed from the comparison over time. Two variation factors were identified in Niger. The first was the closure of the border with Nigeria since September 2019. Some of the declarations relating to trade with Nigeria were excluded from the data.[5] The second variation factor for revenue was structural: imports generally tend to rise as the period of Ramadan approaches, with the dates varying from year to year. It was a few weeks before the start of Ramadan when the health crisis began in sub-Saharan Africa. Variations in revenue and volumes therefore needed to be adjusted for the seasonal factor of Ramadan. The method used was to change the daily timescale, taking the date of the start of Ramadan for each year as day zero. On the new scale, the dates in 2020, 2019 and 2018 are comparable for the first half-year – they are equivalent in respect of the start of Ramadan.

Examples of how Niger’s data were used

The following graphs illustrate how Customs reported on the crisis at the end of each week at different points in the crisis.

Figure 1. Daily variations in revenue and import volumes based on the date on which the situation was recorded

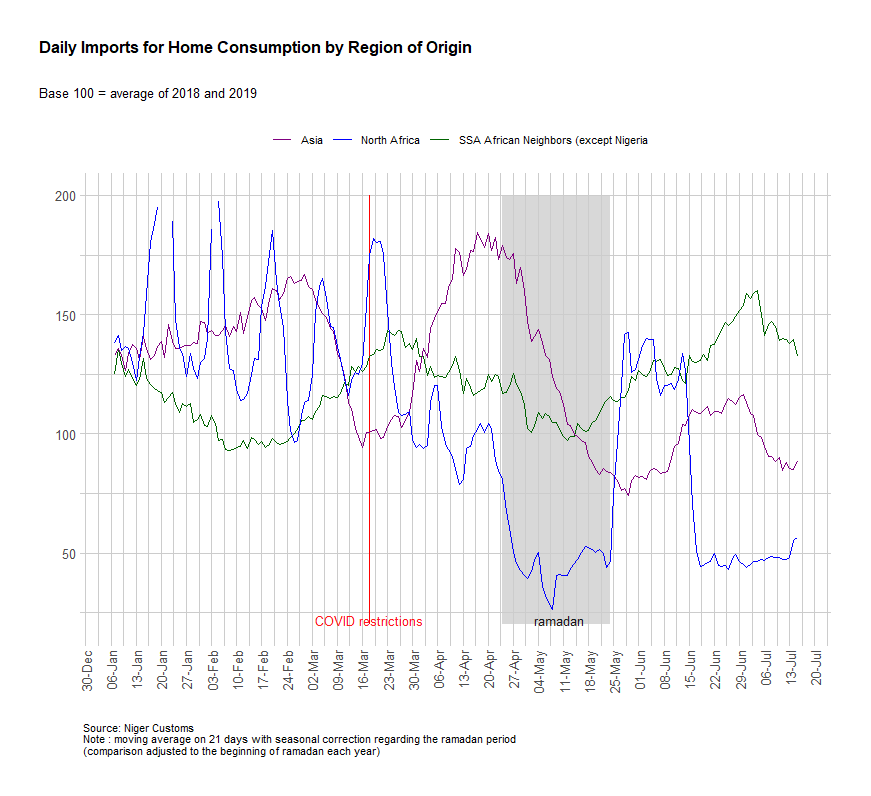

The same kind of method was used by product, by region of origin of the imported goods and by type of importer according to size. One example is shown below.

Figure 2. Daily variations in revenue and import volumes based on the regions of origin of the goods

What the data reveal about the crisis

Over the weeks, the Customs data revealed a V‑shaped crisis: a brutal but short-lived impact followed rapidly by a marked upswing. This outcome is less catastrophic than forecast. This finding during the crisis in Niger subsequently spread worldwide, in particular with the World Trade Organization downgrading the negative impact of the crisis on international flows of goods.[7] The crisis caused a drop in goods flows of approximately 20% over three to four weeks, which is likely to erode the improvement in Customs performance and the normal growth in revenue of between 7% and 10% a year.

During the crisis period, trade in regional products stood up better than “long-distance” trade. The latter has not only been affected by logistical difficulties but has also diminished because the “large” traders have not been able to travel in person to Asia to place their orders.[8] This crisis highlights the importance of regional trade to this country. As further evidence in favour of the promotion of regional trade, in particular through facilitation measures, the impact of this worldwide crisis has been less severe than that of the closure of the border between Niger and Nigeria since September 2019.

The crisis affected “small” traders (68% of the number of importers, accounting for 41% of revenue) less seriously. The level of their imports in 2020 remained higher than the 2018 and 2019 levels. “Large” traders (1% of the number of importers, accounting for 49% of revenue) were more strongly, but still only moderately, affected: their operations primarily involve staple products (rice, cooking oils, sugar) from more distant locations, but they are sufficiently diversified in such a way as to cushion drops in imports in one sector. The category of importers most affected by the crisis is that of the “medium-sized” importers (7% of the number of importers, accounting for 4% of revenue).

As far as the goods themselves are concerned, imports of exempted sanitary products and equipment were particularly closely monitored. From the budgetary viewpoint, as these imports were exceptional, they were not a source of expected revenue, and most operations were being carried out by international organizations or partner countries by way of donations. This inflow of donations and the absence of an initial market for these products meant that these exemptions had no effect at all on revenue.

As regards natural resources, there was no particular drop in exports. On the contrary, some exports saw significant increases, such as gold following the recent exploitation of new deposits.

Lastly, very early on, the data revealed risks of tension on the internal cereal market. Imports of cereals and their by-products dropped sharply. The closure of land borders to travellers and the reduction in transport probably slowed down what is essentially cross-border trade.

Lessons for Customs countermeasures

Lesson one – continuity of service meant that Customs clearance times could continue to be swift. As before the crisis, more than 80% of duties are paid no later than the day after the declaration is filed by the operators.

Lesson two – the Customs bond,[9] a key measure among recommended practices at times of crisis, was not greatly favoured by importers at either the start or the end of the crisis period. More than 70% of operators that had a Customs bond[10] had taken it out in 2018. A few operators requested this facility in May 2020, but the share of revenue paid by means of Customs bonds remained low at around 5% to 7%.

There are several possible explanations for this. Customs had already sharply reduced its processing times before the crisis, and it remained active at the same level during the crisis. Moreover, as we have seen, the volumes imported dropped during the crisis, which inevitably reduced the Customs workload. Importers were not, therefore, penalized by delays in the release of goods or the associated additional costs. Moreover, the period of Ramadan probably did not cause a drop in demand (at most, the crisis significantly reduced supply), so that operators were not faced with difficulties in finding customers and hence in paying the duties and taxes. The last plausible explanation, which is compatible with those above, is that only a few large importers have a structure that is sufficiently sophisticated to open Customs bond accounts with Customs and keep track of them, and they had already opened accounts well before the crisis. Other importers are not well trained or informed enough to take advantage of these benefits.

Lesson three – regional trade is a factor tending to mitigate the effects of the crisis, even if the associated revenue is relatively low compared with long-distance trade, in particular with Asia. Whereas many international political efforts are being expended to help low-income countries in the COVID‑19 crisis, it should not be forgotten that equivalent efforts are still necessary to promote trade between neighbouring countries. In Niger, the closure of the border with Nigeria had an adverse effect on revenue that was at least three times as great as that of the pandemic.

Last lesson – using its data, Customs can effectively help governments to be proactive in a crisis environment where decisions have to be taken rapidly despite the paucity of information available. This article relates only a simple example, but one that was put into practice in real-life conditions. There are other techniques that also rely on the use of transaction data, taking advantage of the “instant” nature specifically of Customs data. The participation of Customs officials in the national crisis unit is a key element of the governmental response: with their detailed knowledge of the actual data, Customs officials can make a useful contribution to the integration of foreign trade data into economic forecasting models, in particular when these models have to be rapidly re‑evaluated before the statistical data are aggregated and consolidated.

There are still several questions outstanding, essentially about the support that should be given to economic operators. An initial question is how to help importers to make better use of the solutions offered by Customs when events arise in which the response time is crucial to cushioning the shock of the crisis. Mid-crisis is not the right time for operators to “learn” to use Customs facilities. A second question is how to provide better help to certain kinds of importers that are particularly vulnerable to changes in the economic environment, typically those that have built up long-distance trade, outside the region, but do not have major financial resources.

In this respect, Niger Customs has opened up a forum with the Chamber of Commerce to provide better information to importers and exporters and to obtain their opinions on how Customs could adapt its facilities to improve crisis response in future. The second action in progress, with the support of the World Bank and the WCO, is that Niger Customs is working on setting up a regional platform to share information on data analysis and, in particular, the use of data during the health crisis. It is at the very time when Customs specialists have the greatest need to meet and exchange views that the health crisis has made conventional regional meetings and workshops impossible. It is therefore important to have a platform in place so that specialists can discuss, in real time, the practices and techniques that are most capable of helping countries to respond to the crisis.

More information

dgdouanes.niger@gmail.com

[1] Approximately 1,000 cases and 69 deaths in Niger for a population of 21 million.

[2] World Customs Organization, web page devoted to Customs responses to the COVID-19 crisis: http://www.wcoomd.org/en/topics/facilitation/activities-and-programmes/natural-disaster/coronavirus.aspx.

World Bank: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/trade/brief/trade-and-covid-19 and https://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/415841588657355986/Logistics-and-Freight-Services-Policies-to-Facilitate-Trade.

[3] See Diego A. Cerdeiro; Andras Komaromi; Yang Liu; Mamoon Saeed, 2020, World Seaborne Trade in Real Time: A Proof of Concept for Building AIS-based Nowcasts from Scratch, IMF Working Paper 20/57, and Gallego, Inmaculada and Font, Xavier, 2020, “Changes in air passenger demand as a result of the COVID-19 crisis: using Big Data to inform tourism policy”, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 2020, pp. 1-20.

[4] The moving average or rolling average is a type of average used, in particular, for time series analysis: trends can be reported with variations smoothed over short timescales.

[5] These were mainly “re-export” operations involving goods from outside ECOWAS imported into Niger to be sold on to Nigeria.

[6] A K-means supervised clustering algorithm was applied using various criteria to distinguish between importers, including their contribution to Customs revenue and the chapters of the Harmonized System in which they operate. Three particular groups were identified, according to their contribution to revenue.

[7] See WTO press release https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/pres20_e/pr858_e.htm.

[8] Interviews with Nigerien traders in May 2020.

[9] Duties and taxes on the importation of goods are payable in cash, in other words the payment has to be deposited at the same time as the import declaration. The Customs bond is an option available to taxpayers to remove their goods by filing an annual bond with the competent department of the Revenue Authority. The bond is a commitment underwritten by a banking or financial institution or an insurance company that the duties and taxes concerned will be paid by a certain date.

[10] Excluding administrations, diplomatic missions and NGOs.