Supporting humanitarian work: some recommended practices

15 June 2023

By Virginie BOHL, senior international expert in devising and implementing strategies to optimize the cross-border movement of humanitarian relief aidHumanitarian organizations are some of the actors operating in fragile and conflict-affected situations. This article looks at the constraints they face, and at how Customs administrations can better support their work.

One in every 23 people needs humanitarian assistance

In December 2022, the United Nations Under-Secretary for Humanitarian Affairs launched the Global Humanitarian Overview 2023[1], the humanitarian community’s most comprehensive evidence-based annual assessment of humanitarian needs and funding requirements. It amplifies the voice of affected people, and it reflects global trends and the drivers of humanitarian need, including conflict, economic crises, disease outbreaks, and the longer-term impact of COVID-19. It is estimated that 339 million people will be in need in 2023, and that one in every 23 people needs humanitarian assistance, especially food assistance. We are indeed facing the largest global food crisis in modern history, driven by conflict, climate change and the threat of global recession.

Fragile contexts and the constraints on them

Fragility, according to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), is the combination of exposure to risk and insufficient coping capacities of the state, system and/or communities to manage, absorb or mitigate those risks.[2] In 2022, 1.9 billion people, or 24% of the world’s population, were living in fragile contexts.

Fragility from this perspective therefore encompasses fragile borders, defined by the WCO as areas where state agencies, particularly Customs, are unable to operate properly owing to the insecurity created by non-state armed groups.

In a fragile context, the humanitarian community faces constraints that can be intentional or unintentional, and that impede a timely, effective and principled humanitarian response. The main constraints observed are listed below.

Insecurity

- Violent conflict continues to take a heavy toll on civilians, including aid workers.

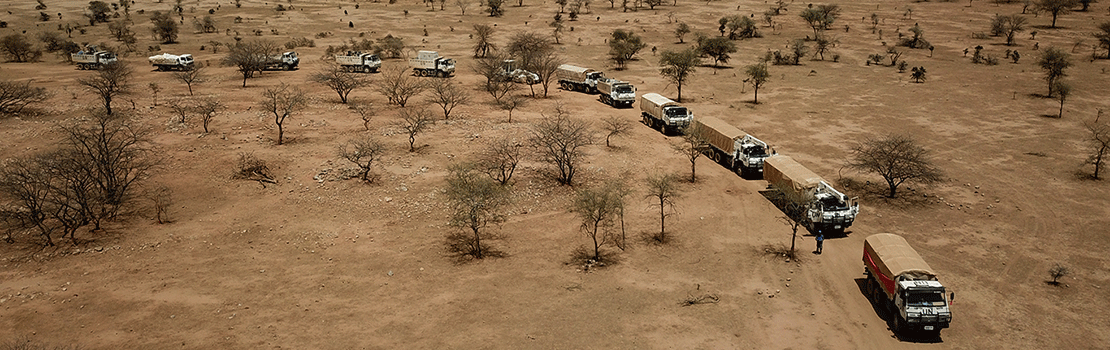

- While in some cases, there is a persistence of cross-border movement of relief aid, in others armed violence and lack of security disrupts humanitarian programmes, affecting the population in need.

Two governing authorities

- Negotiation to access the population in need is complex and difficult as trust must be established with both sides.

- Importing humanitarian consignments implies having to comply with two sets of procedures – which often differ – instead of one, leading to financial burdens.

- Humanitarian imports should be exempted from taxes, but often that rule is not respected in territories where two different authorities are present, and humanitarian organizations may have to pay one of the parties or even both.

- Cross-border agencies may face uncertainty in how to clear consignments.

Lack of or inadequate procedures

- There may be a lack of legislation to support humanitarian organizations, changing or ambiguous regulations, or non-implementation of regulations.

- Procedures may exist but not be published and hence remain unknown to the humanitarian community, resulting in delays in meeting administrative requirements. This in turn leads to higher costs of storage, and more distress and suffering for the affected population.

- Decisions such as temporary closures of border posts may not be communicated in a timely manner.

Restrictions and sanctions

- In territories where anti-terrorism legislation applies, there are restrictions on commodities which may be imported (for example, fuel, armoured vehicles, fertilizers, cement, and medical supplies). Humanitarian organizations can apply for exemptions but the process is slow, costly, and usually requires trained legal staff.

- The United Nations Security Council also imposes sanctions, which range from comprehensive economic and trade sanctions, to arms embargoes, travel bans, and financial or commodity restrictions. Among those, asset freeze sanctions prohibit certain activities which humanitarian organizations are often unable to avoid, such as paying UN-designated individuals or groups for various services, such as food, drink, or transportation, or paying taxes and fees, such as road tolls or utility bills. In December 2022, the Council adopted Resolution 2664[3], which introduces across all existing and future UN sanctions regimes a humanitarian exemption from the asset freeze measures that ban these kinds of transactions, with a view to facilitating humanitarian provision of goods and services. The implementing rules have yet to be adopted.

What can Customs do to support humanitarian work in a fragile context?

In fragile contexts, national institutions need to adapt procedures. In a conflict situation especially, Customs administrations and humanitarian actors must engage in the design of processes enabling the delivery of humanitarian assistance in a timely and cost-effective manner. Below are some measures and actions to be taken:

- Identifying threats and risks early: countries must establish monitoring and alert systems that identify emerging issues before they become embedded, and Customs must be part of the preparation and response mechanism. Political changes (including elections or other transitions of power) should, for example, be closely monitored.

- Understanding humanitarian principles and building trust: Customs authorities must understand and respect humanitarian principles, and humanitarian partners must understand and respect national rules and regulations.

- Defining objective criteria for access to special legal and operational facilities: subject to existing international law, it is the prerogative of originating, transit and affected states to determine which assisting humanitarian organizations will be eligible to receive special legal and operational facilities (versus facilities offered to any humanitarian organization). It is recommended that states define objective criteria to determine which humanitarian organizations will be granted such facilities for the importation of humanitarian assistance. Examples include compliance with minimum standards, with humanitarian principles[4], with the Code of Conduct for the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement and NGOs in Disaster Relief[5], and with high operating standards (for example, ISO certificates for supply processes, inventory controls[6], and the Sphere Project[7]).

- Establishing effective communication channels between humanitarian partners and governmental agencies involved in the import process: humanitarian partners must know which entry points are available, for example, and should be able to discuss how to avoid delays in the import of humanitarian aid, with Customs taking the lead to explore solutions with other agencies. It is important to use technologies to do so. If IT systems do not allow this, it is good practice to establish a WhatsApp group for cross-border agencies and humanitarian organizations to easily communicate. The most recent example is the WhatsApp group created for the “Import and Customs processing on transit to Sudan.”[8]

- Multi-institutional arrangements should establish coordinated working methods between agencies involved in the import of goods: the establishment of a One-Stop-Shop (OSS) mechanism in designated entry points that are safe and secure for both Customs officers and humanitarian staff is a practice which has demonstrated its efficiency. For example, the OSS established in Erbil (Iraq) by the Coordination Crisis Centre and the Ministry of Interior assisted with the Customs clearance of humanitarian cargo arriving in the Kurdish Region of Iraq (KRI) and provided coordination with all relevant authorities. As a result, Customs clearance lead-times decreased by 71%, benefiting 92 organizations, which imported more than 22,300 metric tons of humanitarian aid between December 2016 and November 2018.[9]

“Leave no one behind” is a universal value. However, many people at fragile borders are being left behind because it is often harder, more expensive and riskier to find and assist them. By working together, Customs and humanitarian actors can help ensure that practices and policies do not put unnecessary administrative and financial burdens on humanitarian assistance in these areas.

More information

Virginie.bohl@gmail.com

[1] https://humanitarianaction.info/gho2023

[2] OECD (2022), States of Fragility 2022, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c7fedf5e-en.

[3] http://unscr.com/en/resolutions/doc/2664

[4] https://www.unocha.org/sites/unocha/files/OOM_Humanitarian%20Principles_Eng.pdf

[5] https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/assets/files/publications/icrc-002-1067.pdf

[6] https://www.interaction.org/documents/interaction-ngo-standards/

[7] https://spherestandards.org/humanitarian-standards/

[8] For more information, please contact impacct.2021@gmail.com

[9] https://reliefweb.int/report/iraq/logistics-cluster-iraq-closure-report-december-2019