Fighting corruption in the form of gift-giving: the experience of Indonesia Customs

15 June 2023

By Directorate of Internal Compliance, Directorate General of Customs and Excise, IndonesiaUnder the leadership of President Suharto, Indonesia built one of the world’s largest bureaucracies. It suffered from a range of problems including rampant corruption, inefficiency and poor service delivery. Following democratization in 1998, the country’s political leaders experimented with various public administration reforms. The Directorate General of Customs and Excise (DGCE) was one of the Ministry of Finance departments to pilot the reform of bureaucracy back in 2002. With the improvement of integrity being one of the key expectations of public and private stakeholders, the reform addressed corruption in all its forms, including ‘gratification’.

Bribery versus ‘gratification’

Indonesia adopted two laws concerning corruption in 1999 and 2001 respectively: Law No. 31 on the Eradication of the Criminal Act of Corruption, and Law No. 20 amending Law No. 31. These regulate seven types of criminal corruption:

- an act that causes a loss of state finance,

- bribery,

- embezzlement in office,

- extortion,

- fraud,

- a conflict of interest in procurement, and

- gratification.

Bribery means actively and intentionally giving or promising a reward to a civil servant in the hope that it will help accelerate a process and make it smoother. It involves a meeting of minds between the bribe giver and the recipient. Bribery occurs when there is a deal between the two parties.

Gratification, by contrast, is the receipt by civil servants or state administrators, by virtue of their position, of a gift in the broadest sense, in a manner which is incompatible with their obligations and duties. This includes the provision of money, goods, rebates (discounts), commissions, interest-free loans, travel tickets, accommodation, tourist trips and free medical treatment. There is usually no meeting of minds between the giver and the recipients. However, the gratification can be said to have hidden purpose: the gift is intended to help the giver in future when doing business with the official concerned.

The punishment for the giver or the recipient, is a prison sentence of a minimum 4 years and a maximum 20 years, and a fine ranging from IDR 200,000,000 to IDR 1,000,000,000.

Recipients must report any gifts received to Indonesia’s Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) no later than 30 working days from the date on which the gratuity was received to determine whether it belongs to the recipient or the state. Enforcement is carried out through spot checks, regular inspections or investigation of complaints. A whistle-blower system enables people to communicate information on, or allegations of, such acts. Failure to report these gifts indicates that the recipient is corrupt. The recipient is obliged to prove that the gift they have received is not a bribe and is not incompatible with their position and duties if the value of that gift is IDR 10 million or more (reversal of the onus of proof). For amounts below IDR 10 million, the prosecutor is required to prove that the gift is bribery.

There are specific exemptions for gifts that are not classed as ‘gratification’. For example, government officials may accept souvenirs from meetings, workshops, seminars, conferences or training activities, or accept gifts obtained from a relative or by marriage, as long as there is no conflict of interest for the recipient.

Gratification control units

Withing the DGCE, the Directorate of Internal Compliance is in charge of ensuring compliance with the law and undertaking investigations. As the rules relating to gratification are rather complex, the DGCE soon realized that many Customs officers did not understand when gratification was an actionable crime and when it was not, let alone the correct way to report or hand over the gifts.

In 2013, the Corruption Eradication Commission and the Ministry of Finance decided to sign a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) to support each other in implementing gratification control. To strengthen this function, in 2015 the Ministry established a dedicated unit in charge of such control within the Directorate of Internal Compliance.

The newly created Gratification Control Unit was set up to:

- disseminate information on regulations related to gifts classed as gratification in order to remove ambiguity,

- coordinate the implementation and effectiveness of controls,

- identify risk areas,

- propose measures to prevent corruption and favour integrity,

- receive reports from employees and coordinate with the Corruption Eradication Commission.

Initially, the main focus was to familiarize officials with the concept of gratification. Over the years, it shifted towards the development of a reporting culture within the DGCE.

Understanding that controls on gratification could not be handled by a single unit, in 2017 the DGCE established 136 new units deployed as follows:

- one coordinating Gratification Control Unit in the Inspectorate General of the Ministry of Finance,

- one Gratification Control Unit in the Directorate of Internal Compliance of the DGCE (level 1),

- 23 Gratification Control Units in DGCE regional offices (level 2),

- 112 Gratification Control Units in DGCE local offices (level 3).

Units at levels 1 and 2 comprise 4 officers, and those at level 3 three officers. All of these officers worked within the Directorate of Internal Compliance before being appointed and were trained by their peers or by the officers of the Corruption Eradication Commission.

Each level 3 unit reports to the level 2 unit in its region, which in turn reports to the level 1 unit. The level 1 unit conducts an annual survey of employees on the work of the units at levels 2 and 3. The idea is to identify areas of concern and ways of improvement. The survey shows that employees have a positive view of the units and consider that they help to minimize the risk of corruption.

In 2020, a second MoU was signed between the Ministry of Finance and the Corruption Eradication Commission, providing for:

- access to experts for training purposes,

- information and data exchange between the two parties,

- joint research,

- support in the management of state-owned property, confiscated goods, and goods regarded as gratification,

- the development of a corruption prevention programme,

- human resource development and capacity building.

In 2021, the reporting procedure was digitalized through the introduction of a form on the DGCE website and a mobile app.

In 2022, the units had become a key asset of the Corruption Eradication Commission. They had developed an annual work plan which included:

- the mapping of gratification hotspots in each unit,

- information dissemination to officers and customers/stakeholders,

- measuring the effectiveness of gratification control,

- encouraging employees to report gifts received on religious holidays and other major holidays (Eid al fitr, Christmas, and New Year’s Eve),

- participating in activities organized on the United Nations International Anti-Corruption Day.

By 2023, the units were also handling complex tasks such as analysing gratification reports and coaching officials.

Impact

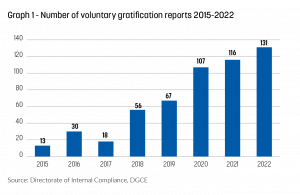

One of the ways of measuring the impact of the units on the level of compliance with the rules on gratification is to look at the evolution in the number of voluntary gratification reports received from Customs officers, as shown in Graph 1.

The increase in the number of reports testifies not only to an increased awareness among staff of what constitutes gratification, but also to increased trust among employees in the organization and its commitment towards integrity. This is important as surveys have shown that the perception of corruption leads to corruption.

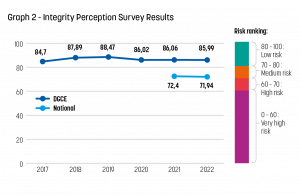

At the organization level, analysis of the gratification reports has enabled the DGCE to identify risky business processes and services, and to collect vital information on the behaviours and practices of both Customs officers and trade operators. Establishment of the units has also enhanced its reputation. Customs staff and stakeholders interviewed by the Corruption Eradication Commission as part of the annual Integrity Perception Survey have given the organization a low risk ranking since 2017.

Lessons learnt

The DGCE believes that, in order to be efficient, corruption prevention must be organized around three lines of defence: first staff managers, second internal compliance and gratification control units, and third the unit coordinating controls in the Inspectorate General of the Ministry of Finance.

The heads or managers working across the administration must become role models and urge their staff to follow anti-corruption guidelines and adopt an integrity culture. The specialized units must coordinate and collaborate with the Corruption Eradication Commission to continuously coach and educate officials about an anti-corruption culture. Finally, the unit at highest level of the system must monitor every aspect of gratification control-related work, from the identification of hotspots, to investigation and measuring the performance of the system as a whole.

Challenges and way forward

Gratification control units face various challenges. The first is to change officers’ perception of gratification and voluntary gratification reporting, which is still “taboo” for many of them. The second is to provide officers who report gratification with support and protection when needed. The law does not provide for such measures, although some officers may be faced with retaliation from the individuals involved. Finally, there is a lack of dedicated facilities and infrastructure, for example, rooms in which to store goods given as gifts regarded as gratification.

After seven years of implementation, it is important that the units keep up the momentum and step up their efforts. They will in future also be focusing on reaching out to Customs clients to prevent illicit acts from their side. This will hopefully encourage officers to “speak up” and report integrity violation without the fear of repercussions or pressure.

More information

tuditki@gmail.com