In Argentina, the Customs, the National Gendarmerie, the Argentine Naval Prefecture, the Airport Security Police and the Federal Police are all responsible for protecting the country’s territory. Cooperating with these agencies is crucial for Customs in remote territories where security is a major issue. This article explains the collaboration framework which is in place, as well as measures taken to strengthen ties and build trust between those bodies. It is also available in Spanish.

Cross-border areas are poles of attraction for unlawful activities

Before joining Argentina’s General Directorate of Customs (Dirección General de Aduanas (DGA)), I worked in different sectors related to international trade, and had a good knowledge of the working practices of the wide variety of actors involved in import and export operations (shipping companies, brokerage, trading companies, and private and public bodies). This was extremely valuable, as my new job consisted in drafting new legislation to suit the needs of the changing trade environment, as part of the DGA Export Technique Department of the Customs Technical and Legal General Sub-Directorate. However, I soon realized that the legislation was not designed in a way which enabled its effective implementation by the Customs officers dealing with operations, and that it generated ineffective procedures which slowed down the movement of goods. To widen my perspective and acquire the knowledge needed for the legislation to meet the operational, logistic, structural and geographic requirements on the ground, I decided to apply for my transfer to a border area.

Overnight, I went from working at a desk in Buenos Aires to La Quiaca, a small city in the north of Argentina, on the southern bank of the La Quiaca River, opposite the town of Villazón, Bolivia. I started my Customs control duties by checking baggage at the Customs office of the Horacio Guzmán International Bridge, which separates both cities. From there, I could see many individuals carrying bags and bulky items with all kind of merchandise as they crossed the almost non-existent river to avoid the Customs control area.

To stop them would have required dozens of officers. But with just over 5,000 officers to control 24 airports, 63 Customs offices, 10 free zones and 154 cross-border posts, inadequate human resources is one of the constraints facing the Administration.

In La Quiaca, like many other border areas, a large percentage of the local population lives off the contraband business. They try to avoid paying duties, excise and other taxes. Some areas of the region have also been taken over by structured criminal organizations that manage intricate logistics networks to move regulated, banned or dangerous merchandise illegally. Taking this reality into account, Customs focuses its control activities on warehouses where goods are stored, and on distribution networks, in order to hit those who orchestrate illegal business.

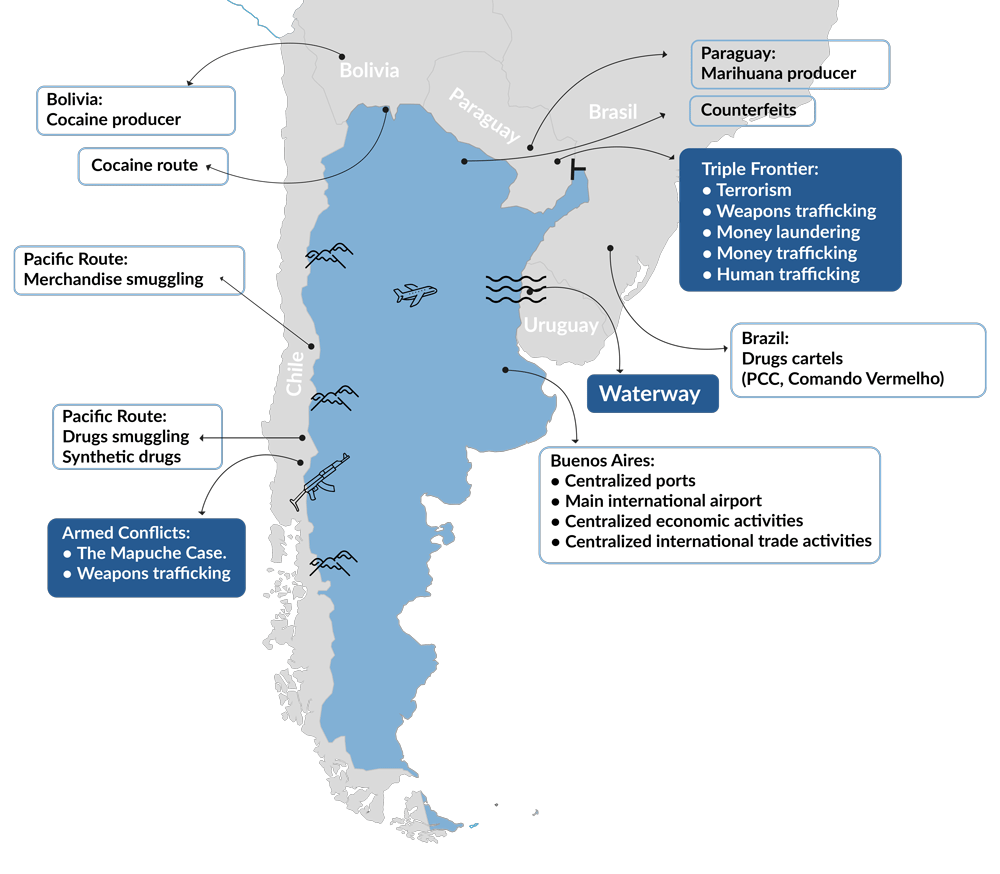

Three specific regions are difficult and can be considered to be fragile borders as Customs may be confronted with violent armed groups with political or financial motivations.

The Triple Border

The Triple Border

The Tri-Border Area (TBA) between Argentina, Paraguay and Brazil comprises three cities: Puerto Iguazu (Argentina), Ciudad del Este (Paraguay), and Foz do Iguacu (Brazil). The border cities rely on revenue from tourism generated by the Iguazu Falls, the largest waterfall system in the world. But they are also known for being major smuggling routes for merchandise such as tobacco, drugs, weapons, endangered species, counterfeit goods, currency and human beings. Most smugglers work on a small scale, but there are also larger criminal enterprises at work.

The Mapuche are a group of indigenous inhabitants of south-central Chile and south-west Argentina, including parts of Patagonia. They demand jurisdictional autonomy, the recovery of ancestral lands, economic-productive freedom and the recognition of a cultural identity. In recent years, some community members have deployed violence against the Federal Police and seized lands. There are constant clashes between the Mapuche organizations and the security forces, creating a context of insecurity for the Customs officers stationed at the border posts in the area. Some extremist factions of these organizations are even credited with setting fire to and destroying, among other things, means of transportation and government checkpoints.

The Paraná-Paraguay Waterway

The Paraguay and Paraná Rivers jointly form a 3,400-kilometre waterway system connecting the river ports of Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia, Paraguay and Uruguay. It is a vast region of more than three million square kilometres, whose surface waters flow into the Río de la Plata, and from there into the Atlantic Ocean. Criminal and smuggling activity is complex as it combines different means of transport (water, land and air), making enforcement extraordinarily difficult. According to the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB), the region is a gateway for the transport of cocaine which is manufactured in Bolivia and Peru and destined for international markets. The “Global Report on Cocaine 2023” of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) also considers this waterway to be the main channel for the export of drugs to the European consumer market.

The challenge of coordinating with security forces

The specificities of each border checkpoint environment (social, economic, geographic and demographic) should determine how control methods and procedures are applied.

In fragile contexts, the nature and size of illicit trade, the degree of violence associated with it, the evolution of working conditions, the degree of infiltration and corruption of criminal networks, the constraints on enforcement operations, and other specific factors, determine the degree of permeability of our borders.

Once threats are identified and needs ascertained, especially when it comes to the equipment and procedures to be put in place to secure staff and operations, Customs must reach out to security forces to ensure actions are coordinated. In Argentina, these are the National Gendarmerie, the Argentine Naval Prefecture, the Airport Security Police and the Federal Police. Law No. 18,711, which stipulates the missions, functions and jurisdictions corresponding to the National Gendarmerie, the Argentine Naval Prefecture and the Federal Police, encourages joint work between these forces when necessary.

The Customs Code (Law No. 22,415) divides Argentinian land, water and air territory into many different areas for the application of its control provisions. For the purposes of this article, the most important are:

- The Primary Customs Zone, where special rules apply to the circulation of people and the movement and disposition of merchandise (for example, ports, docks, airports, border crossings and their facilities, warehouses, squares and other places where Customs operations are carried out).

- The Secondary Customs Zone (whatever is not included in the Primary Customs Zone).

- The Special Surveillance Zone, which is the strip of territory of the Secondary Customs Zone located mainly around the land and water borders (rivers, lakes, sea, etc.) and subject to special control provisions.

Law No. 18,711 gives security forces the function of being auxiliaries of the Customs Service in the context of controls, mainly in the Special Surveillance Zone and in the Primary Customs Zones. In the Secondary Customs Zones, sensitive operations such as arrests or raids are to be carried out jointly with them. All agencies are also to collaborate during investigations and to share intelligence.

Herein lies the main challenge facing our organizations: the application of the procedures, actions and powers granted under the Customs Code, and their coordination with the actions carried out by the aforementioned security forces in their respective jurisdictions. The first step towards meeting this challenge is to recognize the strengths of our organizations, as well as their weaknesses.

Argentina Customs is part of the Federal Administration of Public Revenues (AFIP), an autonomous body within the Ministry of Economy. Its main strengths lie in the competences conferred on it under the Customs Code (Law No. 22,415).

These include:

- To operate in all land, water and air areas subject to the sovereignty of the Argentine Nation. On the contrary, the four aforementioned security forces must act in their territorial jurisdictions (see Law No. 18,711) and may act outside their jurisdictions only with authorization from the Executive Power for order and public safety reasons, or at the request of the Federal Justice.

- To exercise its control powers with regard to people and merchandise, as far as they relate to international traffic in merchandise. In this context, Customs officers may, without prejudice to their other functions and powers and without the need for any authorization, detain people and goods with a view to their identification and registration. They may also adopt pertinent measures in order to stop or retain the means of transport; to inspect, interdict and seize merchandise; and to raid and search warehouses, shops, offices, dwellings, residences and addresses, etc. Security forces can control the means of transport, goods and passengers only with Customs authorization.

- To arrest individuals suspected of smuggling, immediately notifying the competent judicial authority and putting the detainees at the latter’s disposal within 48 hours.

- To access information on natural and legal persons registered in the country in order to investigate crime and to develop risk profiles. This includes information from the Federal Administration’s own records, as well as from the different registries of ownership of movable and immovable property; from credit and financial institutions; from the Central Bank of the Argentine Republic; from the National Directorate of Migration; from the Civil Aviation Administration, and from many other institutions and public and private data centres of interest. Such data is used to initiate, deepen or expand investigations (acting as auxiliaries of Justice); to cross-check information for relationships between suspicious subjects or companies (family, financial, economic, purchases, sales, billing, etc.); to certify information (addresses, ownership, registrations, migratory movements, etc.); to detect abnormal behaviour; and to prepare statistical reports.

The DGA also has good facilities, equipment such as non-intrusive control devices, and highly qualified agents. Finally, it has a small institutional structure and is therefore more agile and less bureaucratic than bigger institutions.

Turning to its weaknesses, for instance, the DGA lacks:

– enough officers in cross-border areas,

– defence capacity (in other words, armed personnel trained in the use of force), and

– access to soft data coming mainly from surveillance and intelligence operations (field research, wiretapping, monitoring, etc.), which are carried out mainly by the federal security forces.

Considering the strengths and weaknesses of each agency is key to coordinating them in pursuit of a common objective and to making the best use of available resources.

Customs and partner agencies are social systems made up of people. Often, officers are unaware of the tasks and duties of their counterparts, have misconceptions about what their counterparts do, or feel that they are in competition and want to claim ownership of results. Building and supporting the strengthening of personal relationships between officers from different agencies is therefore of fundamental importance. Several steps have been taken by Argentina Customs to create ties and foster collaboration with national agencies.

One such example is joint training. The objective is to enable officers from other forces to assist in Customs-related issues, as well as to encourage discussions on ways to meet challenges, to respond to threats, and to exchange information. For instance, at Neuquén Customs, which is located at the border with Chile in Patagonia, we trained the local police officers who patrol the streets and routes on the documentary requirements for Chilean vehicles circulating in Argentina. A couple of days after training was given, the number of illegal and irregular foreign cars discovered increased exponentially.

We also trained officers from the National Gendarmerie, who can exercise controls on cargo trucks on all the routes of the country, in order for them to be able to read international transport documents and identify issues related to international transit operations. This was done mainly in the Mesopotamia region, in the humid and verdant area of northeast Argentina where international trade operations are often used to conceal smuggled goods and drugs. This allows us to have more eyes in the field.

It is worth noting that Customs and officers from the security forces spend whole days or weeks working together at some of the 150 remote border crossings in Argentina, and this ultimately turns these checkpoints into small communities. The objective is to create greater synergy and joint commitment in the fight against criminal organizations, as well as to build trust, and to enable officers to easily share information and exchange experiences.

Finally, formal and/or informal daily interactions that strengthen and deepen inter-institutional ties at the management level are encouraged through the organization of social events and official ceremonies (such as anniversaries and commemorations). By encouraging continuous contact between the most senior managers of the organizations, it is expected that mutual synergy will be stimulated or improved.

The next step: strengthening inter-agency cooperation at the international level

Inter-institutional cooperation is a process that Argentina Customs has taken on board and has been consolidating at a national level. However, the fight against transnational criminal organizations also requires the deepening of inter-agency relationships at the international level. In this regard, the DGA is participating in two WCO projects to promote national and international collaborative work and the active exchange of information: the Colibri Project and the Container Control Programme (the latter being co-managed with the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime – UNODC).

It is also involved in a project led by Argentina’s National Drug Crime Prosecutor’s Office (PROCUNAR), which consists in establishing a Joint International Investigation Team between Argentina and Uruguay. Such teams consist of prosecutors and law enforcement authorities and are established for a fixed period necessary to successfully conclude investigations. The project is carried out with the support of the CRIMJUST programme of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

More information

mvjauregui@afip.gob.ar

dv-inai3@afip.gob.ar