Caught, identified, studied, returned! The role of the British Museum as a source of expert witness for UK law enforcement

27 February 2020

By St John Simpson, Department of the Middle East, British MuseumWhen enforcement authorities or players in the art market suspect that cultural goods have been acquired illegally, they need experts to determine the quality, origin and value of the objects. In the United Kingdom, the British Museum is the expert body they turn to in such cases. In this article, St John Simpson from the Museum’s Department of the Middle East describes the Museum’s role in combating antiquities trafficking and shares some of its success stories in returning antiquities to their rightful owners.

The British Museum is the main advisory body in the United Kingdom (UK) in the event of any enquiries concerning antiquities, and it works very closely with all enforcement agencies and market actors, including the UK Border Force, Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs, the National Crime Agency, the Metropolitan Police Service’s Art and Antiques Unit, the Arts Council, the Art Loss Register, auction houses, dealers, and private collectors.

Protocol

Our expert advice is sought in confidence. If the items prove to be ancient and in breach of antiquities laws, national legislation and/or declaration, we notify the relevant national museum in the country where we believe these objects to have originated, request permission to proceed with the case at hand, and inform their diplomatic representation in London.

If we act at the request of a UK law enforcement agency, we then produce an official report, catalogue and photograph the objects, and in some cases scientifically analyse them in order to answer specific enquiries we may have that either help to support a case or which may have research value.

Our part is then done until we are notified that the objects have been forfeited or disclaimed and may be returned to the country in question. At that point, we prepare a “condition report” and a press release, brief interested arts correspondents in the media, work closely with the concerned museum and diplomatic representation to ensure a smooth handover within a schedule which is mutually convenient, and keep relevant government bodies updated.

This is a protocol we developed first with our colleagues in the National Museum of Afghanistan in Kabul, and since then with the State Board of Antiquities and Heritage in Baghdad and the Ministry of Culture in Uzbekistan. In every case the public impact has been huge and very positive, and we plan to unroll this process as a model for other countries in the future.

Afghanistan

Eleven years ago, in February 2009, we returned 22 crates to Kabul, which weighed over three tons and contained over 1,500 objects seized in Britain between 2003 and 2007. The logistics were complex because of the scale of the operation, and we are very grateful to the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office and the International Red Cross for their generous assistance in physically returning the objects and at their expense.

The returned objects ranged from copper cosmetic flasks, mirrors and weapons looted from 4,000-year-old cemeteries in northern Afghanistan to objects of the Hellenistic, medieval and later periods. Pictures of a selection of the objects were used to illustrate the ICOM Red List of Afghan Antiquities at Risk. Some of the objects were put on display as part of a permanent exhibition in the now-restored National Museum of Afghanistan in Kabul.

In July 2012, just before the London Olympics, we returned a second very large consignment to Kabul, this time with the generous assistance of the British Armed Forces as we routed them on military flights. This group included famous objects stolen from the museum in Kabul during the civil war that had ended up in private hands in Britain and Japan, and which were acquired on behalf of Kabul by John Eskenazi, a respected art dealer. In such cases, our role is that of a third party intermediary. The objects were conserved, scientifically analysed, published, and exhibited at the British Museum before being carefully packed for return.

The above consignment also included 821 looted antiquities of similar periods mentioned earlier, and were amalgamated from five different investigations by the UK Border Force and the Metropolitan Police Service. Some were typical Bronze Age cemetery finds, including copper alloy stamp-seals, cosmetic containers and chlorite vessels, but there were also objects of later periods, such as small stone bowls with coloured inlays, best-known from the heavily looted Hellenistic Greek city-site of Ai Khanum in northern Afghanistan.

Thanks to further scientific analyses, we were able to determine that ancient eye-liner in one 4,000-year-old container was white lead, to identify the species of wood inside the shaft-hole of a Bronze Age weapon and confirm its 19th-20th century BC date by radiocarbon dating, and that some puzzling miniature carved wooden heads were modern fakes, which we radiocarbon dated with a 91.7% probability that they date between 1988 and 1990. We are now finalizing the results and the catalogue of objects, which will be published as a book that also looks at the patterns of looting and illicit trafficking of antiquities from Afghanistan from the 1960s onwards.

The then UK Prime Minister David Cameron announced the return of the goods during the course of an official visit to Kabul. This was followed by a formal hand-over ceremony, and identical press releases in Dari and English were simultaneously issued by the National Museum of Afghanistan and the British Museum, and a number of local and international press articles soon followed.

On 9 May 2016, we were fortunate in being able to return another important object to Kabul, which had also been stolen from the National Museum during the civil war period of the 1990s. The object was an inscribed and dated Safavid tinned copper bowl that had been bought in good faith in Jeddah in 1994 by an expatriate couple then living in Saudi Arabia.

The vendor of the object was an Afghan antiques dealer, and it now looks likely that other stolen or illegally exported Islamic items from Afghanistan were sold through the same route and may one day be successfully tracked down in Saudi Arabia or from other expatriates who worked there at that time.

The expatriate couple had brought the bowl to Christie’s in London, where it was identified as coming from the museum in Kabul and, therefore, impossible to sell at auction: although understandably disappointed, the couple very generously agreed instead to gift it to Afghanistan and we acted as the third party.

We carefully timed this handover to coincide with the arrival in London of President Ashraf Ghani and his predecessor, Hamid Karzai, and that very evening they were shown the bowl. A few days later we received an email saying that the Director of the museum in Kabul had received the bowl, which is now on display in the new Islamic Gallery at the National Museum of Afghanistan.

Uzbekistan

On 18 July 2017, a monumental glazed tile was handed over to Uzbekistan. The tile bore an inscription in “thuluth” script, a form of Islamic calligraphy, which read: “in the year five and six hundred,” which translates to AH 605, or 1208/09 AD. It comes from an important Islamic monument known as the Chashma-i Ayub located in Vabkent, near Bukhara, in Uzbekistan.

The building to which this tile belongs is a special eastern Islamic structure, which served as commemorative monuments and consist of a tomb or memorial within an open enclosure with a monumental entrance. This is one of many in Central Asia that are dedicated to Job, a prophet in the Bible who was known in Islam as Ayyub. In Koranic tradition, Ayyub is regarded as a martyr and prophet who was rewarded with a source of water to soothe his skin afflictions, and in local Central Asian folklore he was viewed as a healer and a patron of silk farming, which was an important part of the economy of medieval Bukhara.

The monument was constructed in the 12th century, but later remodelled during a time when Bukhara was an important Silk Road centre and the provincial capital of the powerful Karakhanid Empire. It was during this phase that a tall entrance was added with a magnificent high-relief turquoise glazed inscription along the top. This tile belongs to the end of this inscription, which reads: “The Prophet – peace be upon him – said: I had forbidden you to make pilgrimages to tombs. Now make pilgrimages. This monument was erected in the year five and six hundred.” The inscription illustrates an important tension within Islam as to whether visiting the shrines of saints was a form of idolatry and forbidden in society.

The construction of magnificent funerary monuments was a feature of Iran and Central Asia, and the combination of a colourful glazed turquoise tile section with relief brickwork is typical of these. This is one of the earliest surviving monuments in the region, and a particularly fine example of the architecture of the era.

This tile had been illegally removed from the building in about 2014 and offered for sale by the London dealer Simon Ray. Fortunately, a former Keeper of Eastern Art at the Ashmolean Museum, who had visited the Chashma-i Ayub, recognized the tile when visiting the dealer’s website. He informed the gallery, and its owner immediately contacted us for advice and brought the object to the British Museum within hours.

We then followed our normal process. The press release included statements by the Prime Minister of Uzbekistan, the Director of the British Museum, and the dealer Simon Ray, with the Uzbek Embassy arranging for the crate containing the tile to be returned. The authorities in Uzbekistan conducted an official investigation and said that the tile would be temporarily held by the State Art Museum of Uzbekistan in Tashkent until it is restored on the original monument itself as part of a high-profile public ceremony.

Iraq

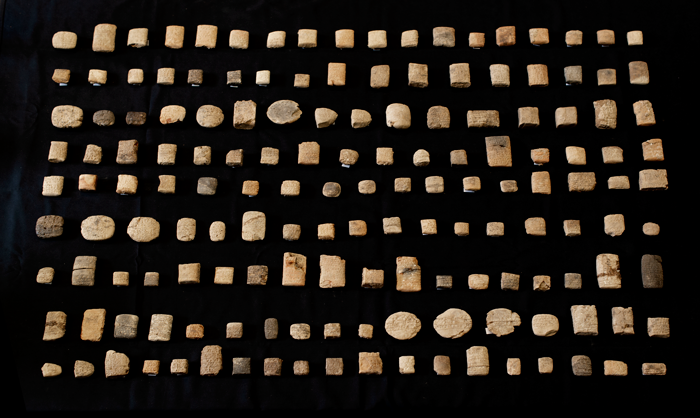

The effectiveness of our process has been noted in other countries and serves as a textbook model and precedent, including for returning goods to Iraq. Since 2018, a large number of Mesopotamian cuneiform tablets, some seals, and a carved Babylonian boundary stone, known as a kudurru, have been handed over to the Iraqi Embassy.

Some items were looted from the site of Tello (Sumerian Girsu), where we have been excavating as part of the UK Government-funded Iraq Emergency Heritage Management Training Scheme. They had been looted in April 2003 in the immediate aftermath of the American-led invasion of Iraq and had gone straight onto the market as they were seized in a raid by the Metropolitan Police Service in May that year, and later brought to us by their specialist Art and Antiques Unit.

The inscriptions on some of the objects not only refer to the site, but also the very temple where they were installed and where we have been excavating. Like the case of the Uzbek tile, there is not a shadow of doubt as to where they were found and to which country they should be returned.

The other objects also came from looting in 2003 and were imports seized by the UK Border Force and investigated at length by Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs. They came from another archaeological site just over 100 km northwest of Tello, where satellite imagery shows a large number to have been systematically pitted.

One of these sites must be the early second millennium BC town of Irisagrig, the name of which was first recorded on tablets looted at that time: tablets from there were seized by the Jordanian Customs authorities in 2003/04, and others have been returned recently to Iraq by the American federal authorities. Wherever else such objects are identified, it is clear that they must have been looted and illegally exported, making them a successful case for repatriation.

Back to Afghanistan

Our latest story takes us back to Afghanistan. In September 2002, the Art and Antiques Unit of the Metropolitan Police Service began investigating another UK Border Force case. This time a group of nine stunningly beautiful painted clay heads and a large carved schist sculpture had been smuggled out of the country via Peshawar in Pakistan.

The objects were brought to us for identification and confirmation that they were of Afghan provenance. The pieces obviously came from one or more Buddhist monasteries and mostly represent men and women who sought to achieve the enlightened status of Buddha, and who were known as bodhisattvas. The women are depicted wearing elaborate diadems whereas the carver of the schist sculpture chose to highlight rich jewellery, in both cases underlining the high status of the individuals.

Photographs were taken of the pieces and circulated to Buddhist specialists who confirmed the similarity of many of the heads to pieces known from monasteries in the Hadda area of Afghanistan, near Jalalabad and on a major ancient (and modern) route connecting Kabul to Peshawar, although the possibility that they came from the site of Mes Aynak, south of Kabul, cannot be discounted.

The Director of the National Museum in Kabul again agreed that we could scientifically analyse and display them before they were returned. Unfortunately, the objects were in a poor state as they had been badly packed and probably suffered in transit. Once more we are indebted to John Eskenazi for coming forward to generously cover the considerable costs of their conservation and mounting for display. Our own Department of Scientific Research also analysed the pigments used to colour the clay sculptures, and three were also CT-scanned so we have a record of how they were made.

We announced these pieces to the press at the launch of the British Museum Annual Review, where our Director, Dr Fischer, outlined the ways in which we work with other museums around the world. At the invitation of the Ambassador of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, we also showed a selection of the pieces to the media at an event he organized to celebrate Afghan Media for Democracy.

For the past three months we have exhibited these objects in a special showcase at the British Museum, where they have been admired by some of our six million visitors a year. This is the first of a series of planned rotations of such material. It is a new and free display designed to explain our role and close liaison with law enforcement agencies and national museums around the world, and show objects to the public prior to their return.

More information

https://blog.britishmuseum.org/art-in-crisis-identifying-and-returning-looted-objects/