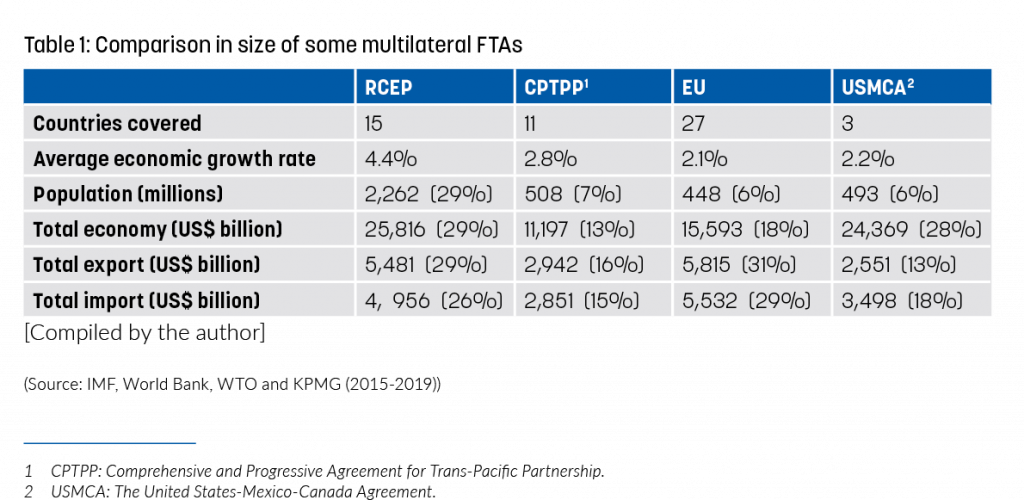

The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) is becoming the world’s largest existing free trade agreement in terms of economic size. Aimed at further integrating the economies of Southeast and Northeast Asia, the RCEP sets high requirements on Customs in terms of procedures, processes and performance. This article looks at the agreement from a Customs perspective and puts forward suggestions for its effective implementation.

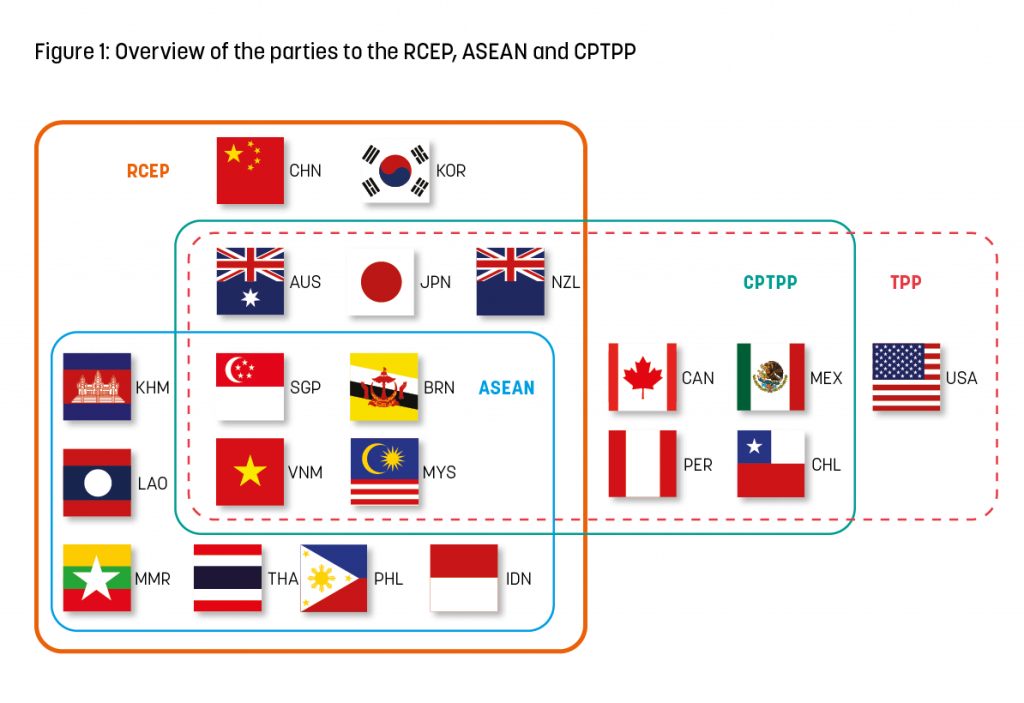

In 2012, the 10 countries belonging to the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)[1] invited China, Japan, Korea, Australia and New Zealand to develop a multilateral free trade agreement. After 31 rounds of formal negotiations over eight years, they finally reached a consensus. The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) was signed on 15 November 2020. It will come into force following ratification by at least six ASEAN countries and three non-ASEAN countries. As at 23 October 2021 when this magazine went to print, Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, China, Japan, Singapore and Thailand had already completed the ratification process. Once ratified by all signatories, it will create the world’s largest free trade zone measured in gross domestic product, covering 30% of the world’s population and accounting for 25% of global trade in goods and services.

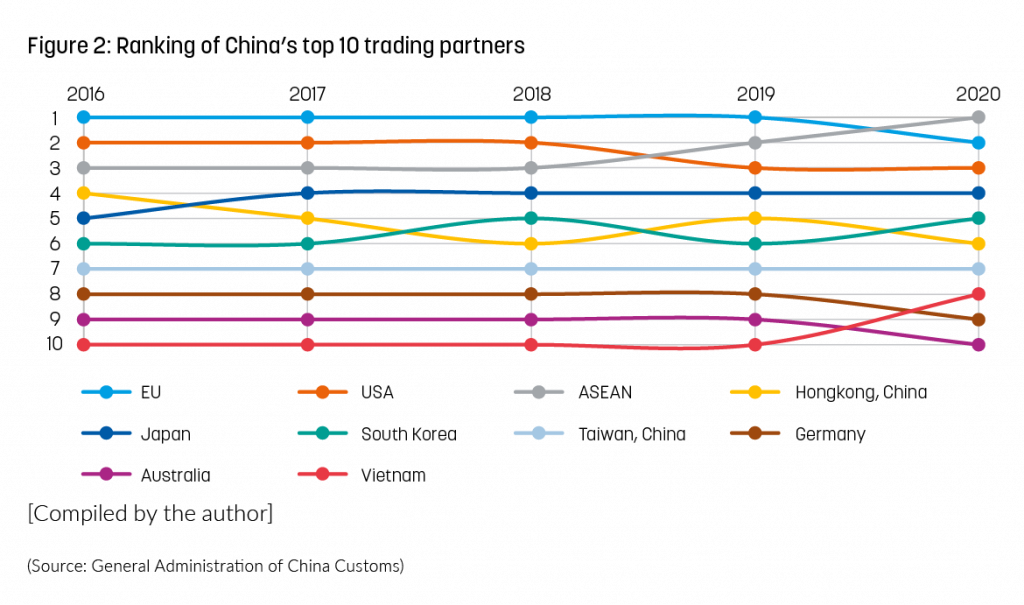

The GDP of Asian countries is on the rise as well as regional trade. Let’s take China as an example. Among the country’s top 10 trading partners in the past five years, there are six Asian countries and the ASEAN bloc. The latter, in fact, became China’s largest trading partner in 2020.[1] The same year, China’s imports and exports to the other 14 RCEP trading partners accounted for 31.7% of China’s total imports and exports. In the first half of 2021, China’s imports and exports to its RCEP trading partners increased by 22.7% year on year.[2]

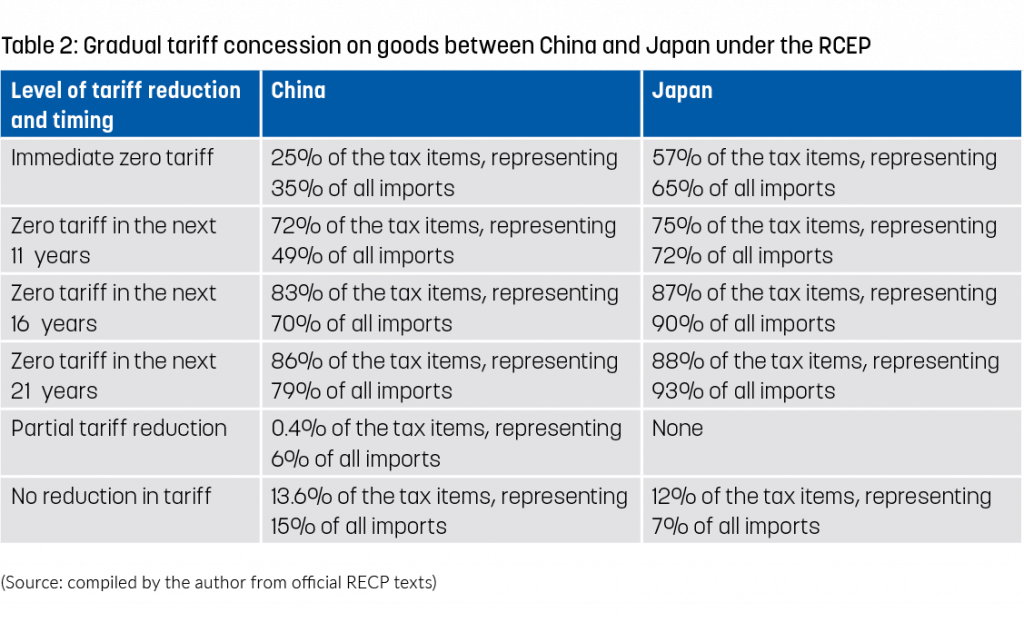

For the first time, China and Japan have agreed on tariff concessions

There is no FTA between China and Japan, and the two countries do not belong to the same free trade bloc. This is therefore the first time that the two countries have agreed on common provisions for trade in services and goods, besides those agreed at the multilateral level. This includes tariff reduction. Currently, both countries apply zero tariffs on about 8% of originating goods. Under the RCEP Agreement, the proportion will reach about 86%. The policy of preferential treatment will be implemented in phases over 21 years, the two countries having opted for a gradual opening of the market (see Table 2). It is worth noting that RCEP will become the basis for a future high-level China-Japan-Korea FTA.

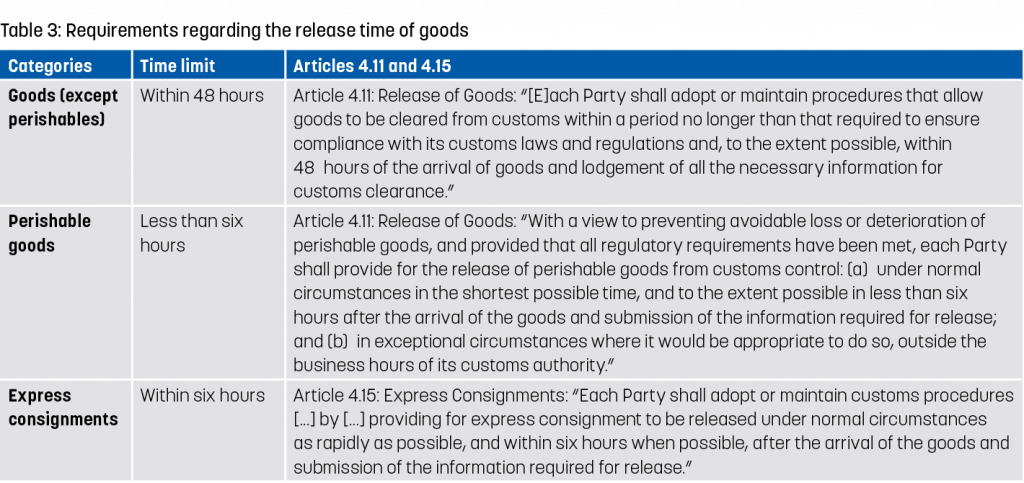

The Agreement stipulates a maximum time limit for the release of some categories of goods

By setting up a time limit for the release of the goods in Articles 4.11: Release of Goods and 4.15: Express Consignments (see Table 3), the negotiators aimed at encouraging the Customs administration of each contracting party to undertake reform and modernize operational models.

As not all parties to the RECP are in a position to implement their commitments from the entry into force of the Agreement, an Annex was added to the Agreement, setting, for some countries, a specific period of time to implement some of its provisions, including those under Articles 4.11 and 4.15.

Logically, the RCEP also encourages Members “to measure the time required for the release of goods by its Customs authority periodically and in a consistent manner, and to publish the findings thereof, using tools such as the Guide to Measure the Time Required for the Release of Goods issued by the World Customs Organization with a view to: (a) assessing its trade facilitation measures; and (b) considering opportunities for further improvement of the time required for the release of goods.”[4],[5]

The Customs Administrations of Australia, Japan, Cambodia, China, Indonesia, Korea, Laos, Malaysia, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Myanmar and Vietnam have all undertaken at least one WCO time release study (TRS). Some have integrated the measurement of the different phases of the clearance process into their electronic Customs clearance system. Some have even developed real-time cargo tracking management. This is the case in Korea with UNI-PASS, which is a Cargo Management System that is connected to delivery companies, warehouses and other private entities involved in the movement of goods.

Harmonized rules of origin and cumulation

Similar to other regional agreements, the RCEP established product specific rules of origin and regional value content. Recognizing its regional nature, the Agreement’s rules of origin provide a means of allowing materials to be cumulated across the RCEP Parties during the production process (Article 3.4). The cumulation provision allows manufacturers to source materials and utilize production processes from across the RCEP Parties and then include these materials and processes in the final determination of whether a good has origin status. On entry into force, the ability to cumulate materials is limited to originating goods, but the Agreement stipulates that RCEP Parties could undertake a future review to consider the extension of the cumulation rule, allowing inputs not meeting the originating criteria to be counted as part of the qualifying content for goods produced and traded between all RCEP Parties. Such a scheme is known as full cumulation.

Requirements regarding Customs procedures

The RCEP Agreement contains trade facilitation measures and other provisions that respond to concerns raised by trade operators regarding non-tariff barriers affecting trade. The impact of the implementation of its provisions is expected to exceed that of the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement, especially in terms of a reduction in trade costs and product prices in the region, as well as an increase in regional trade flows. According to the UN Conference on Trade and Development, exports will grow by more than 10% by 2025 in all RCEP countries.

Requirements listed under Chapter 4 related to Customs procedures are higher than those which can be found in other free trade agreements. For example, parties are requested:

– to issue advance rulings for classification, rules of origin and Customs valuation within a specific timeline set in the Agreement;

– not to exceed the time period set for the clearance of goods;

– to provide operators who meet specified criteria (authorized operators) with trade facilitation measures;

– to apply a risk management approach for Customs control and post-clearance audits.

Recognizing that the Parties are at different levels of readiness to implement some commitments, especially those that go beyond the WTO TFA, this Chapter allows these countries to implement them in stages. Details of the staged implementation of commitments are provided in an Annex to the Chapter.

Parties should use the TRS to its full potential

Conducting a Time Release Study will not only enable Customs administrations to measure their commitments when it comes to clearance time but also to undertake a comprehensive assessment of the effectiveness and efficiency of border procedures, including those of other border and regulatory agencies. It will also enable administrations to identify gaps and needs, and, if the TRS is carried out regularly, to monitor and measure the outcomes of the implementation of specific RCEP measures and associated policies and programmes.

The TRS can be conducted at specific points of entry and the methodology adapted to focus on specific goods or procedures, such as express delivery and perishable goods. The RCEP Contracting Parties could explore the possibility of coordinating TRS at the regional level to get an overview of the average time required to move goods among Parties and identify their needs in terms of capacity building and reforms.

Customs must ensure that rules of origin are understandable and workable in practice

The Agreement was negotiated based on the 2012 edition of the HS. With a new edition of the HS entering into force on 1 January 2022, there will be a need for the rules of origin laid out in the RCEP to be revised and updated. In countries that will implement the 2022 edition of the HS as from next year, goods would have to be classified twice – using the 2022 edition of the HS for classification purposes, and the 2012 edition for origin determination – if the rules of origin in the RCEP are not updated.

The RCEP rules of origin have provisions relating to transport requirements. Like in the ASEAN Trade in Goods Agreement, the term “direct consignment” is used which is, as it was highlighted at the Second WCO Conference on Origin, “neither in line with modern commercial practices, nor with Customs procedures”. The Agreement provides for evidential requirements to verify that no manipulation or alteration of existing documents, such as bills of lading or invoices, has taken place. But it does not limit them to such documents, referring to “a non-manipulation certificate, or other relevant supporting documents, as may be requested by the Customs authorities”. In practice, there will be a need for Customs to provide some clarifications and to limit evidential requirements to existing documents.

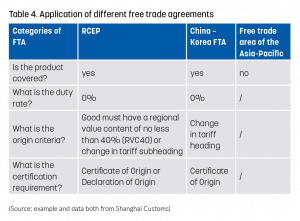

Table 4. Application of different free trade agreements

Source: example and data both from Shanghai Customs

As it was explained in a previous edition of WCO News, “Customs administrations […] are well placed to address the inconsistencies and confusion attaching to procedures laid down in trade agreements”. It is suggested that the Customs administration of each Contracting Party provide training to trade operators and develop supporting information management systems in an effort to make it easy for importers and exporters to declare the origin of goods and, in general, to facilitate compliance with the various provisions of the Agreement. The Chinese Government is working on the development of RCEP Country of Origin Management Measures and Approved Exporters Management Measures. These sets of measures aim at reorganizing the process of managing the issuance of RCEP certificates of origin and promoting “self-certification of origin”, a type of certification of origin which utilizes a declaration of origin or a self-issued certificate of origin as a means of declaring or affirming the originating status of goods.Most RCEP Parties already have FTAs in force with each other through a combination of bilateral and plurilateral agreements. Trade operators wishing to claim preferential treatment will therefore have to choose between at least two agreements. Customs administrations may want to set up a consultation service to help businesses understand which FTA best fits their interests.

More information

tonghua@shcc.edu.cn

[1] Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam.

[2] Chenggang Li, “Three reasons that make ASEAN China’s largest trading partner”, Economic View China, 27 September 2020. http://www.jwview.com/jingwei/html/09-27/351053.shtml (available in Chinese only; last accessed on 27 July 2021).

[3] Report from Yingjie Dang, Deputy Director-General of the National Port Administration Office of the General Administration of China Customs on the regular briefing on State Council policies held by the State Council Information Office on 29 July 2021.

[4] Source: RCEP Article 4.17: Time Release Studies.

[5] For the TRS Guide, see https://mag.wcoomd.org/magazine/wco-news-87/new-version-trs-guide