Illegal logging under the microscope

26 February 2020

By Alec Dawson, Forests Campaigner, Environmental Investigation AgencyThe global demand for timber, and its products, is only partly being met from legal sources. According to a 2012 report from INTERPOL and the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), illegal logging accounts for between 15 and 30% of the volume of all forestry products. This share is even higher in tropical countries where 50 to 90% of timber is deemed to have been logged illegally.

Multiple implications and impact

The implications and impact of this trade are devastating on many levels as illegal logging cuts across borders and social lines:

- The economic impact leads to losses for state coffers through, for instance, the loss of tax revenue.

- The social impact includes the undermining of the rights and livelihoods of people, including indigenous peoples, living in and around forests (there are estimated to be 6 billion forest-dependent people around the world).

- The environmental impact, to name a few, is seen in the loss of natural forests and habitats for wildlife (a major cause of the current climate crisis, especially as the conversion of forests to agricultural land, for example, accounts for roughly 12% of global greenhouse gas emissions), and in the increase in the number of natural disasters witnessed today.

It is expected that the appetite for timber will continue to grow, with the World Bank, for example, forecasting that demand in 2050 will be four times higher than 2015 levels. In fact, it will be even more devastating if illegal timber continues to be a source, as this would signal a wholesale failure of governments, including Customs administrations, the private sector, and civil society to address this problem.

While the situation may seem somewhat bleak, significant efforts are, however, being made to address illegal logging and its trade. Such efforts include global agreements, legal reforms, increased investment in enforcement, and cooperation within and between countries.

Legal framework

One of the key global agreements is the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) that came into force in 1975. CITES, which has 183 signature countries, aims to ensure that the international trade in wild plants and animals does not threaten the survival of the species in the wild. The Convention covers over 35,000 species, of which about 84% are plants. Under CITES, all importing countries are required to monitor this trade to ensure that shipments of CITES-protected animals and plants are accompanied by legitimate licences.

Although the list of species protected by CITES does not include many timber trees, it is growing. For example, the endangered Siamese rosewood (Dalbergia cochinchinensis) was added in 2016, along with over 250 other rosewood species. This follows many years of campaigning by the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), bolstered by the release of its report entitled “Routes of Extinction: The corruption and violence destroying Siamese rosewood in the Mekong,” which was translated into Chinese, Thai and Vietnamese.

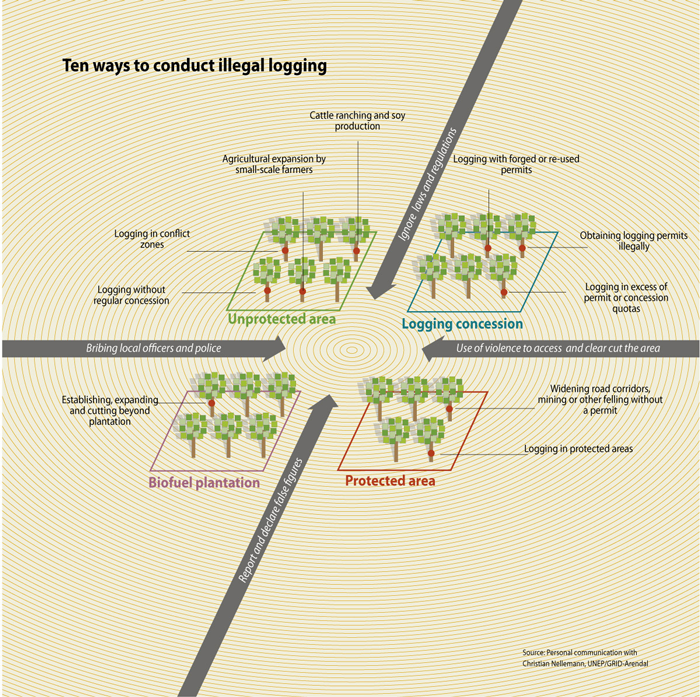

Many enforcement agencies primarily focus on CITES breaches, but, when we talk about illegal timber we refer to any wood that is harvested, transported, and traded in violation of national laws. It is acknowledged that there are various types of illegal logging that can be differentiated, although many of these activities are interrelated (See Graph “Ten ways to conduct illegal logging”). The restriction at the national level is given not least because there is neither an overarching international regulation against illegal logging nor an internationally-accepted definition of what illegal logging encompasses.

One of the gaps in many national laws is that it is entirely legal to import and market timber and timber products, produced in breach of the legislation in the country of origin – i.e. the country where the trees were harvested. However, some countries now require importers to ensure that the products they purchase have been legally harvested.

This is the case in the United States (US) under the Lacey Act, which makes it possible to prosecute anyone knowingly in possession of illegally sourced wood. The aim is to impose penalties on the possession or importation of illegal timber in order to suppress demand, thereby eliminating or reducing the profits derived from this traffic. Australia and the European Union (EU) have taken similar measures. More recently, the Chinese government also revised its Forest Law, which now stipulates, in Article 65, that “no entities, nor individuals shall buy, process, nor transport illegally sourced timber.” This recent news coupled with, for example, efforts by the US and the EU, provides reasons to be optimistic.

EU regulation

The European Union Forest Law Enforcement Governance and Trade (FLEGT) Action Plan deserves specific mention. Adopted in 2003, the Plan is more than a piece of legislation. Rather, it was designed to address the root causes at the heart of illegal logging – rampant corruption, poor governance, lack of transparency, and much-needed accountability from those trusted with managing forests.

FLEGT sets out a range of measures available to the EU and its Member States to tackle illegal logging in the world’s forests and supports improvement in the supply of legal timber as well as increased demand for timber from responsibly managed forests. It includes seven measures that together prevent the importation of illegal timber into EU markets, one of which is the Voluntary Partnership Agreements (VPA).

The VPA is a legally binding treaty that the EU negotiates with a timber-producing country that exports timber and timber products to the region. Through multi-stakeholder consultations, a definition of legality is agreed upon that includes the reform of laws to ensure a transparent chain of custody, which is verified, including through civil society monitoring. Once agreement is reached, a FLEGT Licence is then issued for the export of timber from that country to the EU.

Another component of the Action Plan is the European Union Timber Regulation (EUTR) that includes due diligence requirements and a prohibition on illegally sourced timber entering the EU market. The EUTR places responsibility on the individual or organization placing the timber on the market to conduct due diligence, in order to ensure that the timber is in compliance with the laws of the country where it is harvested.

The first VPA to be signed was with Ghana, followed by the Republic of the Congo, Cameroon, Indonesia, the Central African Republic, Liberia and Vietnam. In addition, the EU has concluded negotiations and initialed VPAs with Honduras and Guyana. Currently Indonesia is the only country that issues FLEGT licences.

Enforcement agencies

Fundamental to the success of combating the trade in illegal timber, including through the EUTR, is enforcement. Cooperation is one important avenue to support enforcement. This cooperation can take many forms, with one key area being between Customs administrations of importing and exporting countries, as well as with other relevant government agencies. Also important is information from the ground that is collated and verified by third parties, including independent civil society monitors.

Produced by TRAFFIC and the WCO, the publication provides information on illegal timber flows, how to carry out risk profiling, the harmonized Customs codes that should be used for timber and timber products (and how to identify them), and legislation pertaining to the timber trade and forest certification schemes. The publication can be found on Environet or by contacting the WCO.

Organizations such as the WCO, working with its partners like INTERPOL, are investing a great deal in fostering collaboration among Customs administrations and relevant enforcement bodies to curb the illicit trade in various commodities, including through enforcement operations. One of these, Operation Amazonas, focused on timber.

Set up in 2014 under the initiative of Peru Customs, Amazonas saw Customs and law enforcement authorities in various countries in Latin America, as well as China, working together to identify timber and timber products logged and traded illegally. One of the main lessons learned during the operation is that cooperation among all the government agencies responsible for supervising and checking legal titles is key to efficient enforcement as “without this cooperation, it is impossible to ensure the traceability of the trees that have been removed.”

In June 2019, the WCO and INTERPOL coordinated Operation Thunderball, with Customs and police officers carrying out joint enforcement action in 109 countries. Besides the wide range of seizures of wildlife and their derivatives, the operation also saw the seizure of 2,551 cubic metres of timber (equivalent to 74 truckloads). Thunderball marked a new direction in the WCO/INTERPOL partnership, bringing them together to ensure that trafficking in wild fauna and flora is addressed comprehensively from detection to arrest, investigation and prosecution.

EIA’s contribution

Civil society organizations, including the EIA, are also playing an important role in helping to address the trade in illegal timber. Their role includes acting as a watchdog and sharing information with relevant agencies, for instance with Customs administrations.

The EIA’s forest campaign aims to combat the illegal timber trade by investigating and exposing the actors responsible for sourcing and trading in illegal timber. The organization’s work includes conducting undercover investigations, as well as using data to identify patterns in illegal trade and the individuals and companies responsible, while lobbying the relevant authorities to take action.

One of the EIA’s major campaigns is combating the trade in high risk Myanmar timber, particularly teak, into the EU. Myanmar has one of the world’s highest rates of deforestation (e.g., according to government data, forest cover fell from roughly 47% in 2010 to 43% in 2015 (equivalent to nearly the size of Belgium), and illegal logging is a major contributor to the problem, with timber harvesting massively overshooting legal harvest limits imposed by the country’s Forest Department. At meetings of the competent authorities responsible for enforcing the EUTR, it was agreed that it is not possible to adequately mitigate the risk that Myanmar teak is illegal when importing it into the EU.

Since 2015, the EIA has laid complaints (called “substantiated concerns” in the EUTR), related to Myanmar teak importations against 15 companies across six different EU Member States. The vast majority of these complaints have resulted in enforcement action being taken against the companies concerned. Actions taken include warnings and injunctions preventing companies from continuing to import Myanmar teak into the EU. For example, the German competent authority has issued a warning to all operators that Myanmar teak does not meet the requirements of the EUTR, and confiscated a shipment of timber in 2019, ordering it to be returned to the country of origin. Data obtained by the EIA indicates that in countries where there has been enforcement action, a substantial reduction in the inward trade of Myanmar teak has been observed.

Results and remaining challenges

Data collected by the UNEP’s World Conservation Monitoring Centre, which acts as a consultant to the European Commission and compiles overviews of the checks performed by EU Member States as well as of timber source countries to support the implementation of the EUTR, shows that competent authorities are fairly active in enforcing the EUTR. For instance, during the period December 2017 to December 2018, these authorities checked a total of 1,419 companies, finding 452 of them to be non-compliant with the EUTR’s requirements, and issuing 240 notices of non-compliance and 76 penalties.

Although this suggests the competent authorities are engaging with the regulation, the proportion of penalties compared to companies in non-compliance is quite low. Financial penalties are also typically not very large by comparison to the value of timber being traded. Recently, a UK furniture company was fined 13,000 pounds sterling (roughly 17,000 US dollars) for failing to comply with the EUTR, having already been issued a notice of non-compliance. It is unlikely that this level of penalty is truly dissuasive for other importers of high risk timber.

While Customs are often not the competent authorities responsible for enforcing the EUTR, they can be at the “frontline” of ensuring companies are not importing high risk or illegal timber. Customs can identify if timber may be high risk and alert the competent authorities accordingly. They can also be responsible for enforcing injunctions placed on companies in violation, and seize or hold timber coming into the EU if that timber is potentially illegal. Recently, an enforcement action was conducted in Belgium against a company importing timber from Gabon with the assistance of Belgian Customs.

Violations of Customs offences in countries of harvest can also render timber “illegally harvested” for the purposes of the EUTR, as the applicable laws for the EUTR include legislation related to trade and Customs. These include incorrect classification, declaration of one species in place of another, and undervaluation. For example, an enforcement action reported by the EIA in February 2019 in Trieste port in Italy involved the temporary seizure of Myanmar teak on the basis that a larger amount of timber was declared arriving in the port than the amount that had departed Yangon – suggesting a possible misdeclaration to avoid taxes in Myanmar. The scale of the problem in Myanmar in only financial terms is demonstrated by the fact that, as reported by Forest Trends, Myanmar government data recorded 29 million US dollars of timber exports to China during 2014 and 2015, whereas China reported more than 550 million dollars of timber imports from Myanmar for the same period.

Addressing illegal logging in Myanmar is a significant challenge as highlighted in the EIA’s 2019 report entitled “State of corruption: The top-level conspiracy behind the global trade in Myanmar’s stolen teak,” with the report recognizing the importance of enforcement agencies, including Customs administrations, in, for example, China, the US and Europe stepping up efforts to halt the trade in teak from Myanmar. The report also highlights the challenges of holding companies to account in an environment of poor governance. In this context the value of the work of Customs administrations cannot be over-emphasized when considering the scale of the illegal logging issue not only in Myanmar but throughout the world.

Companies can attempt to evade enforcement of the EUTR through two methods. Firstly, where an injunction has been placed on a company, they can use other companies or proxy companies to import timber instead, and then simply receive the timber once it has cleared Customs. Secondly, companies may use an entirely different country as a landing point for timber, on the basis that enforcement may be weaker in that country.

Although the EIA’s data reveals a decline in imports of Myanmar teak in countries that have enforced the EUTR, this has been matched by an increase in imports in other countries. However, it is possible to identify this kind of evasion and take action against it. In December 2019, cooperation between the Dutch and Czech competent authorities led to a seizure of Myanmar teak that had landed in Slovenia and was travelling through the Czech Republic to eventually reach the Netherlands.

Customs can once again be the “frontline” in identifying all forms of circumvention. If the same people are importing timber with new company names, or if timber is landing to be immediately shipped to another country, Customs can identify situations where circumvention may be occurring.

While EUTR enforcement is an encouraging step in the fight against the illegal timber trade, challenges remain, including for Customs administrations. In particular, identifying shipments that are high risk is often problematic, additionally it is often difficult to effectively prosecute breaches of the law, and timber traders are also proving to be resourceful in attempting to circumvent enforcement.

The same challenges exist for the enforcement of wood products covered under the CITES. An additional difficulty is to appropriately identify wood products (such as Siamese rosewood) to species level. In a recent article[7] entitled “Fraud and misrepresentation in retail forest products exceeds U.S. forensic wood science capacity,” researchers found fraud and misrepresentation in 62% of tested retail forest products in the US.

The authors emphasized the importance of technology in supporting compliance and law enforcement at a relevant, commercial scale, and highlighted the need to invest in a systematic capacity development programme, including hardware to achieve this. Again, efforts are being made, including through the Global Timber Tracking Network, which is developing a global database of DNA and stable isotope fingerprints of major commercial timber species. This database could be used by laboratories to help verify that the species listed in the documents attached to the timber is correct.

Conclusion

The financial value of the trade in illegal timber should be an argument strong enough to convince government agencies to invest in combating this type of crime. Adding the environmental and social implications should make these agencies realize that the stakes are so high that inaction or lack of progress is not an option.

Against such a background, Customs is urged to continue working with other authorities, especially to address the low level of penalties currently imposed, to support legal reforms when needed, to ensure laws are designed with enforcement in mind and cannot be easily circumvented, and to make sure enough investment in resources is made to shut down this lucrative and devastating illegal timber market.

More information

alecdawson@eia-international.org

https://eia-international.org/forests/