How digital tools can improve compliance with SPS measures

24 February 2021

By Francis LopezGiven increasing concerns about food security and food safety and the need to fight hunger and eliminate food waste, a review of the current processes for implementation of the World Trade Organization (WTO) Sanitary and Phytosanitary Agreement and adoption of information technology to enhance workflows would benefit both the import and export economies, as well as trading partners.

SPS Agreement and certification process

The aim of the WTO Sanitary and Phytosanitary Agreement (SPS Agreement) is for WTO Members to exercise their right to “take sanitary and phytosanitary measures necessary for the protection of human, animal or plant life or health” without imposing unnecessary barriers to trade. It typically applies to trade in, or movement of, animal-based and plant-based products within or between countries or Customs territories. Governments are encouraged to use international standards, guidelines and recommendations when developing SPS measures.

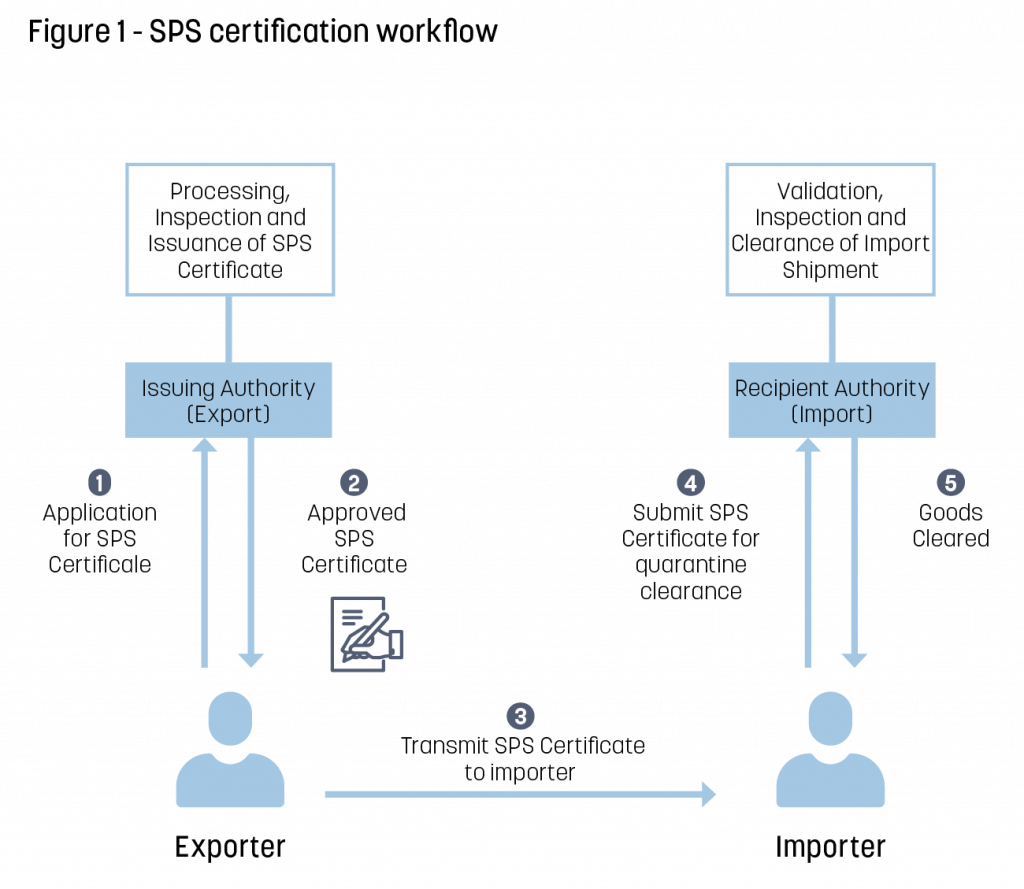

Many importing countries require a Sanitary/Phytosanitary Certificate which is an official document issued by a competent authority of the exporting country to the exporter. It certifies that the animals or plants, and their derived products, covered by the Certificate have been inspected and are free from pest and diseases. Other steps include applying for an import permit, submitting other certificates related to health and community safety, and presenting the commodities for quarantine inspection before clearance for release.

The SPS governing bodies[1], under the Food and Agriculture Organization, have standardized the format and data contents of SPS certification on paper. The Certificate, based on the prescribed format and printed on paper, is issued to the exporter who then sends it to the importer for presentation to the competent authority of the importing country. The SPS Certificate workflow from the export authority to the import authority is depicted in figure 1 below.

Digitization of document flows

The SPS governing bodies have developed standards for digitization of SPS Certificates. The IPPC has developed ePhyto Certificates (ePhytos) and provides descriptions of the format and contents of ePhytos, the mechanism for their exchange and guidance on harmonized codes and schemes. The OIE has also developed standards for electronic veterinary certification and the Codex has done the same for food items.

Many countries have managed the transition to electronic SPS certification. All experts agree that before moving to a digital system, an effective paper-based certification system needs to be in place with adequate institutional capacity and clarity about roles and responsibilities. However, many countries still only accept paper certificates at import, including some countries that are actually capable of producing e-certificates. In such cases, a paper version of the certification will still be provided to the exporter for submission to the importer along with other documents. The importer will then, in turn, submit the paper SPS Certificate to the import authorities.

As with all initiatives for implementing paperless processes, the main challenges relate to:

- agreeing on institutional arrangements between parties involved in cross-border electronic information exchange (voluntary versus binding schemes/all agencies versus only identified agencies, etc.);

- establishing a supporting legal framework that officially recognizes electronic transactions and electronic forms of authentication, as well as addressing liability in the event of processing errors and for dispute resolution processes;

- building a sustainable business model with a clear revenue model; and

- agreeing on an electronic data interchange (EDI) standard, namely communication protocols and document structure standard, to ensure that IT systems cannot only issue electronic certificates but also accept and read certificates issued by other authorities.

To address some of these issues, in 2018 the IPPC embarked on implementation of the ePhyto Hub Project to enable the exporting National Plant Protection Organization (NPPO) to send phytosanitary certificates electronically to the central Hub, for retrieval by the recipient importing NPPO. Countries using the Hub do not have to establish bilateral agreements required for point to point systems. A generic national ePhyto system, i.e. GeNS, was similarly developed for countries which do not have a system to produce ePhytos and send them to the ePhyto Hub.

Cross-border exchange

When regulatory border agencies all have access to data through a national Single Window, Customs authorities can view the import permits issued by the quarantine authorities and, by the same token, the quarantine authorities have access to manifests and goods declaration data submitted by the importer. Upon arrival of the goods, Customs and quarantine officers both conduct verifications to prepare for clearance of goods. Customs officers focus on the goods declaration data and on tariff classification for the purpose of collecting the corresponding duties and taxes, while the quarantine officers focus on compliance of the import commodities with the prescribed SPS measures, and particularly with the SPS Certification issued by the export authorities.

Interagency cooperation and data exchange at the national level is well established in most countries. Looking beyond the exchange of electronic certificates, efficient cooperation processes are also required between authorities in the countries of import and export.

Import authorities sometimes ask the export authorities to replace the SPS Certificate. Reasons for rejection of the Certificate may be that it has been tampered with, is a fake, has expired or is no longer valid due to a change in the SPS measures of the importing country. This may result in additional storage charges for the importer. What is more, if the importer does not have proper storage facilities then spoilage and/or wastage of goods is likely.

As already stated, in an effort to facilitate controls and eliminate unnecessary delays in the release of cargo, SPS issuing authorities are providing quarantine authorities with electronic certificates, through direct exchange, by using platforms such as the ePhyto Hub or by providing access to their IT systems. However, the development of tools enabling enhanced exchange of information on rules and certifications could further improve the trade in agrifood products.

Enhancing transparency and compliance

Over and above facilitating exchange of information between authorities at the international level, there is also a need to provide transparency on SPS measures and, once again in this case, digital tools could prove a game changer.

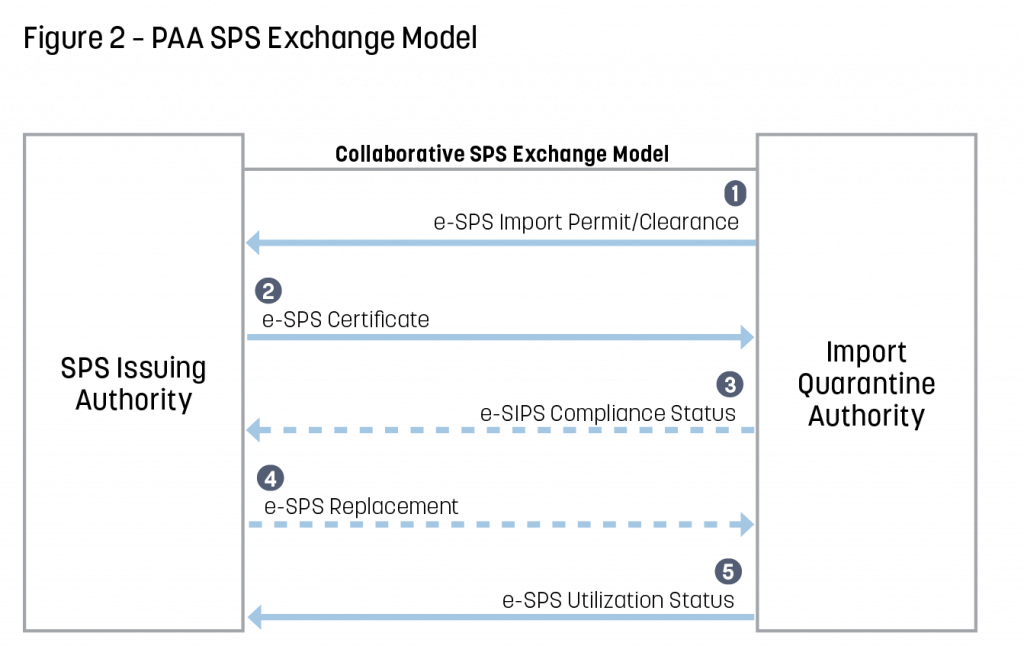

Some private sector-led initiatives are worth mentioning. One of them is by the Pan Asian

E-Commerce Alliance (PAA) which aims to promote and provide secure, trusted, reliable and value-adding IT infrastructure and facilities to enhance seamless trade worldwide. The PPA conceptualized a Collaborative Exchange Model to facilitate cross-border trade in agrifood products, whereby the SPS issuing authority and the import quarantine authority would share permit/clearance requirement data and SPS Certificate data.

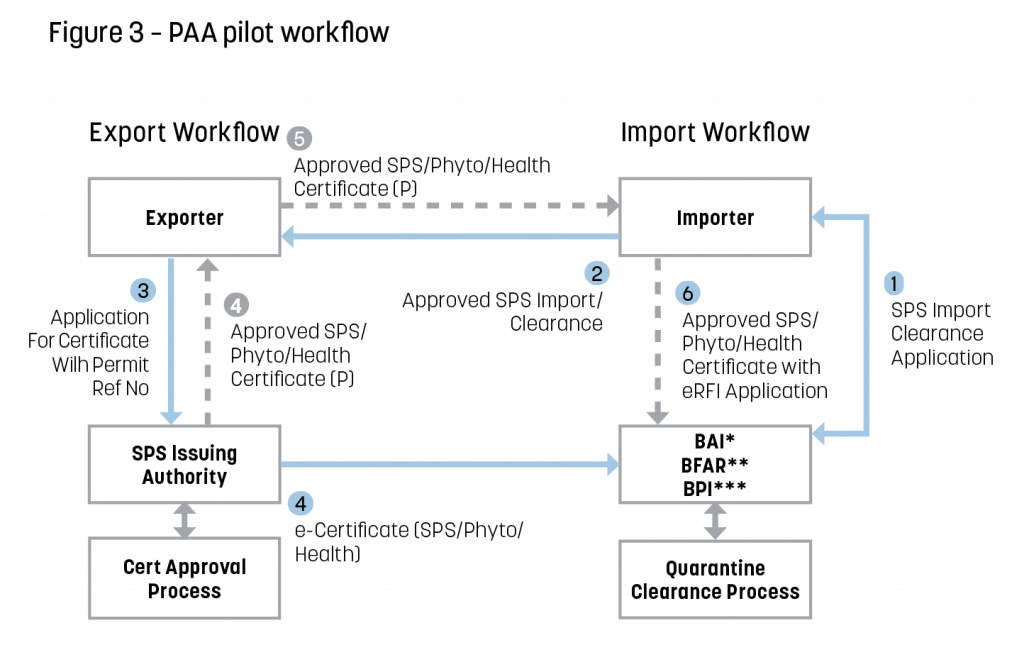

In a pilot exercise between the respective Departments of Agriculture in the Philippines and Australia, the import permit issued by the Philippines was made available to the exporter based in Australia to ensure the latter was aware of the type of authorization issued to the importer and of the specific certification and procedural requirements for importation (e.g. the validity of the import permit based on the must-ship-out date). In addition, the SPS Certificate issued by the Philippines included the import permit reference number to facilitate verification, possibly through automated matching of the permit and certificate data, and to ensure that the above-mentioned SPS Certificate was compliant.

The process established during the pilot exercise enabled the exporter to eliminate risks of non-compliance of the goods with the import country’s SPS measures. It illustrates the fact that many digitization projects are an opportunity to review procedures in place, enhance transparency and strengthen compliance.

More information

flopez@intercommerce.com.ph

[1] Three international standard-setting organizations are recognized by the WTO SPS Agreement: the International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC) for phytosanitary standards; the Codex Alimentarius Commission for food safety standards (Codex); and the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) for animal health standards.