Assessing the cargo release process: Brazil shares its experience

24 February 2021

By Brazil CustomsThe WCO has long emphasized that the Time Release Study (TRS) is a useful tool with which a country can assess the performance of its Customs administration, border regulatory agencies, port authorities, trade operators and various service providers, in terms of the clearance process. In this article, Brazil Customs shares its experience on conducting its first TRS.

Undertaking a Time Release Study (TRS) is an effective way to obtain a wide range of information and insights related to the clearance process and the processing of trade transactions by the various actors involved. Although the tool was developed by the WCO years ago, Brazil Customs did not launch its first TRS until 2019. In fact, the Administration had been using another methodology to measure the time required to release goods. That methodology, whilst sharing some similarities with the TRS, was not satisfactory: it focused on the Customs perspective only, and did not take into account all the entities involved in the import process (e.g. licensing agencies and private sector bodies).

After undertaking two assessments using the methodology, the Customs Administration finally turned to the WCO TRS. Previous attempts to assess clearance performance had prepared the ground, and decision-makers were already sensitized to the importance of collecting data on the time required for the release of goods. In particular, they were aware of the importance of measuring performance against the target release times set out in various projects, and of assessing the impact of statutory and administrative changes on trade behaviour over time.

Challenges

The Administration was faced with numerous challenges during the preparation and implementation phases of the TRS:

- High-level support had to be secured, as conducting a TRS requires resources, as well as the capacity to instruct other agencies and participants.

- There was a lack of personnel to run the Study, and the Administration had to release officers from some of their existing duties to enable them to focus on the TRS project.

- Effective partnership had to be established with the private sector representatives participating in the Study to ensure that they felt involved and collected the required data.

- Modifications had to be made to the Customs IT system in order to have access to and extract all the required data.

- Some agencies involved in the clearance of goods had difficulties in collecting the required data.

It is possible to run the Study in adverse situations; however, Brazil Customs preferred to launch its first TRS when the necessary conditions were all met.

Methodology

The Study was conducted at all border crossing points where clearance takes place. The exception to this was the road mode of transport, for which data was collected at the two main points of entry of goods, representing approximately half of the total volume imported in this mode. The data relates to the time taken from the arrival of the goods in the country to their actual physical exit from the bonded warehouse. It was collected for three modes of transport (sea, air and road) and four “inspection channels”.

Four main flows were identified and the import process of each flow was broken down into different stages in order to precisely identify those responsible for each of the procedures and, consequently, facilitate the identification of opportunities for improvement in processes and performance.

Bearing in mind the degree of digitization of Brazil Customs and trade stakeholders, as well as the massive amount of data which needed to be collected and the number of entry points involved, it was decided that all the data should be collected electronically. Data was collected from the Customs IT system and then shared with all the entities participating in the Study, who were asked to supplement it. In total, data was collected on more than 300,000 declarations. Once adjustments were made to reduce this volume of data, that figure fell to around 260,000 declarations.

Findings

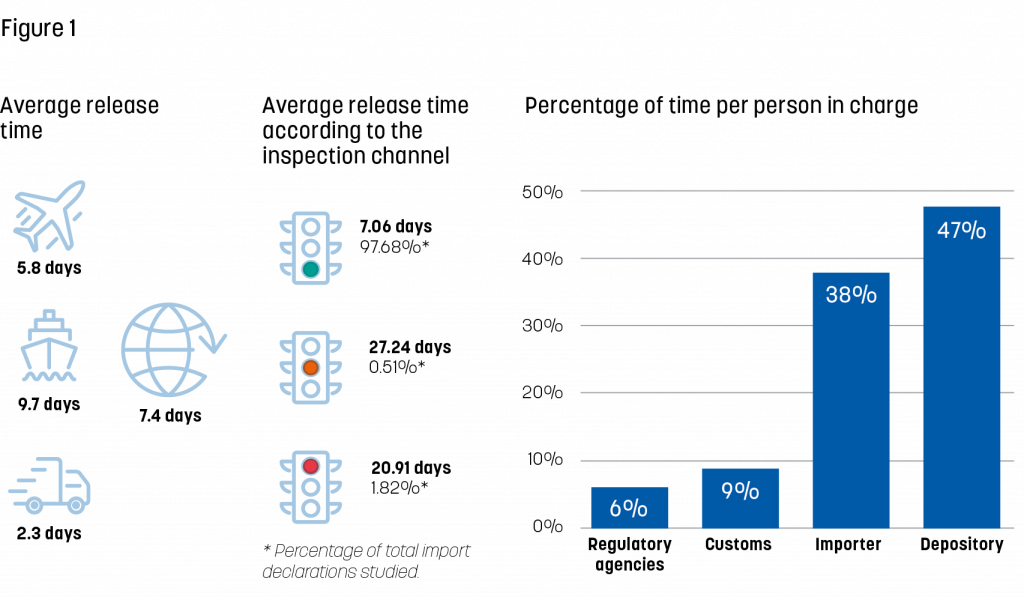

The main findings of the Study in terms of release times are presented in Figure 1. The average time for a cargo to be released is 7.4 days. Clearance times increase according to the inspection channel (green, yellow or red). Import processes that present a higher Customs, sanitary and/or phytosanitary risk have more complex import flows. The highest average release times were identified in these processes, which represent less than 3% of the sample.

The Customs clearance stage, where responsibility lies with the Customs Administration, accounts for less than 10% of the total time measured. The actions which are the responsibility of private agents, notably importers or their representatives (Customs brokers), international carriers and depositories, represent more than half of the total time spent in all flows analysed.

It seems that many opportunities exist for the various private sector entities involved in the importation process to speed up the release of cargos. Diligent action by importers and/or their representatives in carrying out procedures for registering declarations, delivering the goods after clearance and handing of documents to Brazil Customs and other relevant agencies has the potential to generate an average reduction of more than 40% of total times.

Opportunities also exist to review performance indicators developed to assess the impact of introducing future reforms and tools. For example, the project team in charge of the development and implementation of Brazil’s Single Window Programme, the main tool for modernizing and reducing bureaucracy in Brazilian foreign trade, had set the objective of reducing the time required to release goods in the maritime sector from 17 days (the average time being taken) to 10 days. The TRS findings show that it takes 9.7 days meaning that the objective set could have been more ambitious.

Other key findings are:

- The processing times for some procedures differ from one Customs office to another. There is a need to identify the reasons for such disparities and develop best practice in order to harmonize the way procedures are applied.

- The time required by importers or their representatives to register the import declaration, and the time required to deliver the cargo to them, represents roughly 80% of the total average time required. In light of this evidence, Brazil Customs needs to start a dialogue with the private sector to understand the reasons for such processing times.

- The import procedure is still based upon a series of sequential steps, and this impacts negatively on the time required for clearance. The Single Window project team has mapped the existing sequential process, and a procedural change is expected to be introduced as part of the project implementation.

- An imbalance has been identified in the distribution of workloads among Customs units. There is a need to redistribute tasks among national and regional teams. One of the constraints to take into account is the available IT infrastructure, as some tasks require access to specific tools.

- There are gaps in terms of technological infrastructure and IT services among public bodies. This will be resolved with the implementation of the Single Window environment.

Authorized Economic Operator

A specific section of the TRS was dedicated to the time required to release consignments from importers who had received Authorized Economic Operator (AEO) status. Another section dealt with consignments for which regulation was the responsibility of the health authority and the agriculture authority, and for which importation required licensing before or after arrival in the country.

The TRS shows that, while normal operations take an average of 207.38 hours between cargo arrival and delivery, AEO operations flow 32.37% faster on average in all modes (140.25 hours). One of the benefits offered to certified AEO operators is “Clearance on Water”, a special clearance method for the sea mode of transport that allows for advance registration of the import declaration. The Study proved that these sea mode operations achieved a significant time reduction of 72.47% on average. However, the use of Clearance on Water is limited to imports where no licensing is required, or the licensing procedure is carried out before registration of the declaration. The Government’s decision to involve other Government agencies in the AEO certification process by implementing the “Integrated AEO Programme” is a window of opportunity, as it will enable operators certified as Integrated AEOs (in terms of Customs and the respective consenting body involved in the operation) to use Clearance on Water for imports subject to licensing.

Transparency

The results of a TRS and any other performance measurement activity should be published. Standard 9.1 of the WCO Revised Kyoto Convention provides: “The Customs shall ensure that all relevant information of general application pertaining to Customs law is readily available to any interested person.” This idea is reiterated in the WCO Transparency and Predictability Guidelines, which list the “results of performance measurements” among the information that Customs is encouraged to publish.

Not only should results be made public, but “experiences in measuring average release times, including methodologies used, bottlenecks identified, and any resulting effects on efficiency” should be shared, according to Article 7 (paragraph 6.2) of the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement.

In Brazil, the methodology and the results of the TRS were presented during an online event which brought together high-level representatives from various domestic institutions, private sector entities and international organizations, including the WCO. As well as this event, a webinar was organized for those looking for more detailed information. Both were viewed by thousands of people. The TRS report, various presentations and the Study’s anonymized bulk dataset are available to the public on the internet. Publicly communicating results can be a very effective motivation factor for all actors involved in the process of clearing goods and enable accountability and transparency obligations to be met.

Indirect benefits

The TRS results can be useful in many areas.

Research

The Study dataset could be of interest to academia. By analysing the anonymized bulk data, it would be possible to make new findings and even to refute some of the conclusions, or to come up with new recommendations.

Human resources

Numbers are a universal language. They reflect an intelligible and neutral understanding about what is happening on the ground. The work of Customs officers is reflected in the TRS. With the data collected, it is possible for those at managerial and executive level to shed light on situations and practices that were previously only discussed hypothetically. The Study made it possible to establish a dialogue with the objective of building engagement and increasing a sense of ownership of projects. Issues and needs identified could be addressed by adapting procedures, providing tools or delivering training.

Customs-Business partnership

The Study makes it clear that the actions and improvements of procedures by public agents are not enough, given that a large proportion of bottlenecks relates to private agents’ responsibilities. Since there is a common interest in making the release of goods more agile, public officers and private sector representatives should see this as an opportunity to build better relations and to collectively find answers to issues identified in the Study.

Bringing in tangible data in support of the policy debate

The conclusions and recommendations from the TRS were included in the action plan of the National Committee on Trade Facilitation (NCTF). In this way, a technical study has entered the political sphere and will help shape reform.

In Brazil, besides the NCTF, there are Local Committees on Trade Facilitation (LCTF). These are managed by local Customs units and serve as a forum to discuss facilitation initiatives at the local level and to address local issues. They also have to report to the NCTF the questions which require decision or guidance from national level. Data collected during the TRS provides new insights into the local realities, and the Local Committees are expected to discuss measures to be taken to tackle issues identified in the Study and to monitor their implementation.

Conclusion

Carrying out the TRS in Brazil was challenging, but the benefits it brought to the cross-border trade community, as well as to the country as a whole, were worth it.

The TRS is seen as an ongoing process and Brazil Customs is committed to conducting a TRS regularly. The main bottlenecks identified in the TRS have already been mapped and, as already said, for most of them, medium-term solutions are already being developed. Once they are implemented, it will be important to measure again the release process to assess the gains obtained. In other words, the TRS is expected to act as a trigger and baseline for the assessment of future developments. Hopefully, upcoming editions of the Study in Brazil will reflect these advances and improvements.

More information

ronaldo.sf.correa@rfb.gov.br

jackson.corbari@rfb.gov.br

jose.carlos-araujo@rfb.gov.br